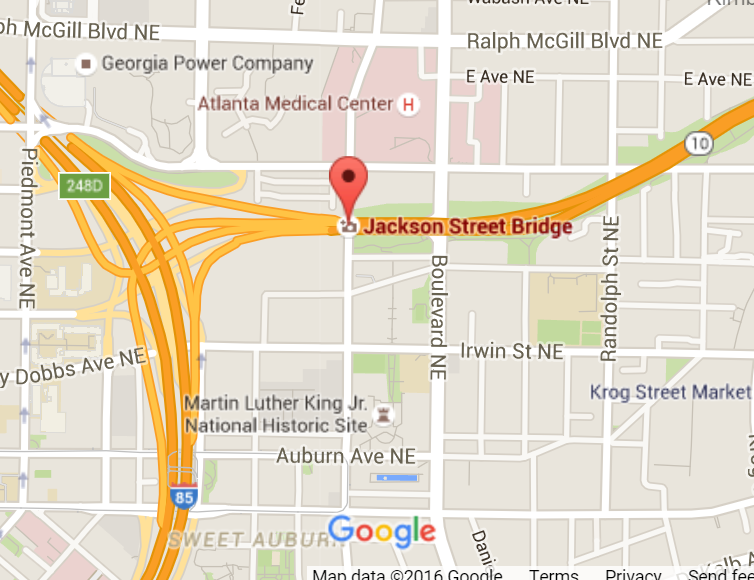

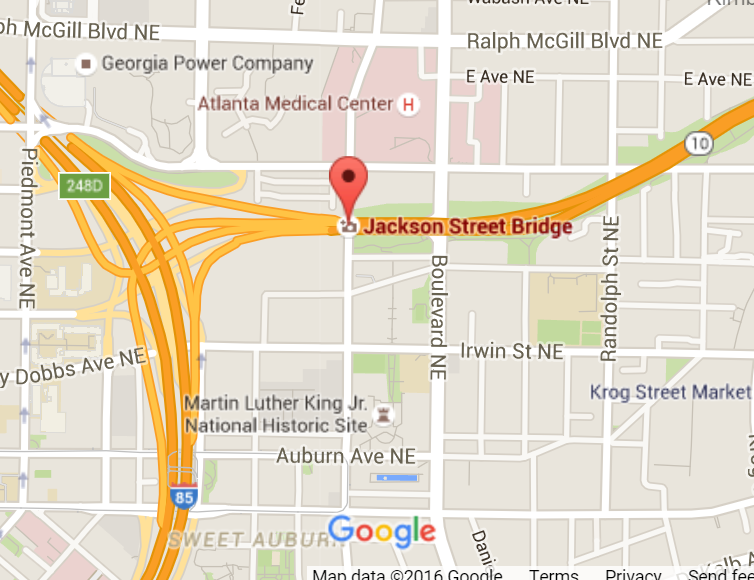

The “picturesque” view from the Jackson Street Bridge is something that most people don’t recognize on the internet or on television. It is the unknown phenomena; the view that has seen so many faces but the faces hasn’t seen it. The bridge is considered the best place for anyone to get an eye-full of Atlanta without spending a penny. In relation to places, the bridge is between the Martin Luther King Jr. Historic Site and Atlanta’s Medical Center. The bridge is right above Interstate 75, looking right ahead to the inner connection of highways in Atlanta or the Freedom Parkway.

Location of the Bridge

The history behind this 50+ year old bridge is that it was fought for by the people. The implications of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 lead to mass deconstruction of urban housing. In Georgia, the Department of Transportation planned to have Interstate 75 run right through some historically African American neighborhoods like Old Fourth Ward and Sweet Auburn. Many people were pushed out of their homes but those that stayed fought for justice in court. The ending compromise resulted in the construction of this very bridge. They didn’t realize that they were going to create an amazing hotspot for future residents and tourists to enjoy.

It’s an easy place to access once you realize where it is. Riding a bike there works too because a bike lane is provided which is quite convenient. There are houses and apartments on each side of the highway. The opposite side of the bridge has houses and parts of the Martin Luther King Historic site. Most people who stop here are photographers, local residents, and tourists coming to take selfies with the Atlanta Skyline. Many people have been seen walking their dogs across the bridge to get to the park provided by the MLK historic site.

-

-

View from the right side of the bridge

-

-

View from the left side of the bridge

The first time you may visit this place might seem intimidating and mesmerizing however the bridge level and rail is pretty low. It’s not a good idea to stand close or lean over the bridge while looking at the view because you could tip over! The feeling of cars rushing under you makes you want to look over the bridge but don’t. When taking pictures, be mindful of where you stand! The sounds you might hear depends on the time of day. Interstate 75 is quite busy throughout the day so you will hear tons of car horns and traffic. The colors seen during the day are green and blue. The blue comes from the sky; hugging the buildings, while the green come from the grass surrounding the highway.

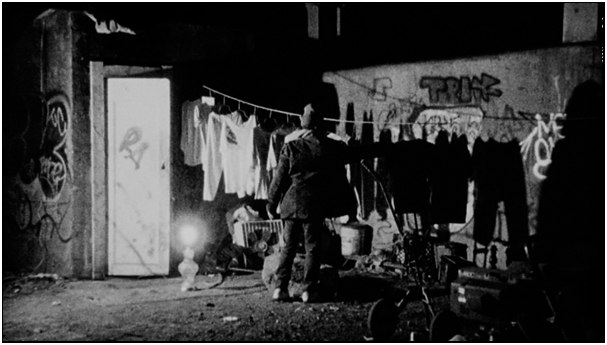

In contrast, during the evening, the sounds are very serene and discreet. You will hear quite a few cars driving by but nothing too loud. The colors become black. There are only a few lit places on the highway and bridge because of streetlights. The lights in the different buildings faraway look like millions of stars in the sky. Because of the view and vibe at night, it is considered to be a romantic places. Couples tend to display their love on this bridge and often leave something behind.

-

-

Jackson St’s view at Night

-

-

Love left behind at the bridge

Sources used to assist –

Corson, Pete. “Golden Hour at the Jackson Street Bridge.” MyAJC.com. Atlanta Journal Constitution, 13 Feb. 2015. Web. 2 Feb. 2016.

Dominey, Todd. “Atlanta’s Jackson Street Bridge.” Todd Dominey. Todd Dominey, 9 June 2014. Web. 02 Feb. 2016.

Jackson Street Bridge, Jackson Street Bridge. Personal photograph by author. 2016.