Gallery of Morton’s Pictures

- The darkness is consuming

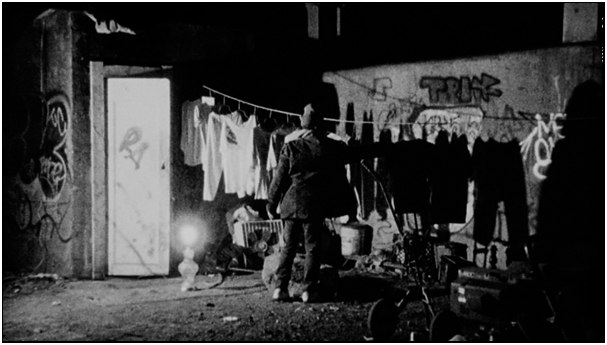

- Morton’s Tunnel picture

- Consumerism isn’t a thing

- Decoration shows ownership

- Homeless do with what they have

- Tents represent privacy of space

- Parallels

The article, Tapestry of Space: Domestic Architecture and Underground Communities in Margaret Morton’s Photography of a Forgotten New York, written by Irina Nersessova talks about Margaret Morton’s photographs of New York’s homeless populations’ home life and it’s parallel with the life of someone who is housed. Morton’s photographs captures the everyday life of the displaced in New York. According to Nersessova, homelessness is as nothing different as someone who is housed. Morton’s pictures depicted that the homeless have a home. The only difference between the housed and the homeless is the level of stability of their home.

In reference to Morton’s photographs, the homeless use their space as a creative guide just like a homeowner would. The decoration acts as an indicator that the space is theirs. An example would be that a homeowner might name their home with their last name. The same goes for a homeless person who puts their name above their space. Unlike a homeowner, the homeless will use material scraps that they find whereas a homeowner can go out and purchase letters to put on a mailbox or a fence that will be placed in front of the entrance. Nersessova goes on to say that “…the displaced best represent the universal relationship between space and the splintered identity.”

Ideally, a home is a place where you often feel safe. A homeowner will feel safe in their home because it isn’t likely that an unwanted guest will intrude. Even more, it can act as a refuge to get away from the outside world. This idea can apply to a homeless person as well. The public are usually unfamiliar with a developed homeless society like New York’s tunnel. Consequently, they will ultimately end up ignoring them, making the place perfect protection from the outside world. The only difference is that the homeless have definite security; it’s a paradox, because a place so open, compared to a house, should be less safe. However, as Nersessova explains, “The absolute darkness of the tunnel prevents danger from entering it, which explains how it is possible to have the highest feeling of safety in a place that is perceived as most dangerous.”

Most often, people will think that the homeless are undesirable that don’t contribute to society; however, they are mistaken. The displaced persons in Morton’s pictures, live in the world of mass production and capitalism just as housed people do. The only difference is how their contribution has an effect on their psychological attitude. A homeowner contributes by maybe owning a business or purchasing products from a privately owned business. Nersessova goes on to describe how consumerism can consume a person, forcing them to demand for excess. A homeless person contributes by using the thrown-away products by the product-obsessed population. Some may use those products to keep them warm, to decorate their space, or help them make a little change in order to buy supplies they may need. Nersessova voices how their mentality can’t be reduced to commercialism due to their lack of resources.

As described above, the homeless life isn’t that much different from the ones whose home is more stable. A homeless person’s space can feel just as safe as a house to a homeowner, if not more. A homeless person can definitely decorate their space to indicate ownership just as a land owner can. In addition, a homeless person’s contribution is very much desired in society as a homeowners does, even if society; itself, doesn’t realize it. Furthermore, the parallels between the housed and the homeless demonstrated in Morton’s photographs aren’t very noticeable at first but as Nersessova breaks down those misconceptions in this article, a reader can begin to visualize Morton’s purpose.

NERSESSOVA, IRINA. “Tapestry Of Space: Domestic Architecture And Underground Communities In Margaret Morton’s Photography Of A Forgotten New York.” Disclosure 23 (2014): 26. Advanced Placement Source. Web. 26 Jan. 2016.