Madison Brooks

Dr. Robin Wharton

Engl 1102

20 April 2016

Segregation is Not Over

As Atlanta, Georgia made steps to recover after World War II, African Americans were treated as second-class citizens by Caucasians as commercial expansion uprooted their homes and inner city development was used to push them out of the city and into the suburbs. As a result, African Americans and Caucasians began and continue to settle in separate communities.

African Americans and Caucasians live segregated mainly because Caucasians physically forced African Americans out of their existing homes and into the suburbs. After World War II, programs intended for reconstruction wound up only benefiting wealthy, politically powerful men (Bullard 12). These men were uninterested in improving areas of deteriorating poverty in the city. Federal programs such as anti-poverty projects were gradually ignored, and as a result failed miserably. For example, Atlanta begun the Model Cities Program in 1966 in an effort to fix the problems in Atlanta’s low-income neighborhoods, which were mostly inhabited by African Americans (Holliman 21). The program was substantially underfunded and understaffed and did little for the living conditions of the select neighborhoods. Instead of finding other ways to improve these lower-class areas, politicians’ solutions were to simply destroy these “slums” and create new developments over them in the race to expand Atlanta into a tourist destination (Holliman 21). As well as African American families forced out of their homes, the larger activity in private development compared to federal government programs, caused Caucasians to steadily drive an increasing gap between the social classes of Caucasians and African Americans (Pooley).

In the 20th century, in addition to ignored reconstruction programs, the Central Business District of Atlanta began to rapidly transform into a tourist destination, which lead to increased private and commercial development as well (Holliman 3). Developers destroyed entire “slum” neighborhoods without a second thought in order to create this tourist destination that would in turn bring thousands to the city (Pooley). This uprooted hundreds of African American families, which left them homeless and pushed them out of the inner city and into the less developed suburbs. This mainly left the Caucasians isolated in their city communities. The expansion of the Civic Center in 1967 as well as the World Congress Center, Omi Complex, Hyatt Regency hotel, and much more brought in a large amount of tourism, but many of these developments again forced families out of their homes because the new buildings were placed directly on top of existing neighborhoods. This redesign of Atlanta displaced more than 55,000 African American families (Newman 305) and pushed African Americans into areas away from the main attractions, such as Auburn Avenue and Decatur Street. These streets became known as the “black” streets because they were underdeveloped and inhabited by lower income citizens. This caused Caucasians to stay away, which left these streets isolated to developers and businessmen, which kept tourists at a distance as well. In addition to these streets, many areas in Atlanta played a major part in African American history such as the Civil Rights movement, and were therefore preserved by historical groups and still stand there today (Newman 315). Because of this preservation, many of these neighborhoods remained highly populated by African Americans. Where most African Americans in the mid to late 1900’s settled after the historical events and redesign of Atlanta is where many continue to live today.

Certain types of development, often referred to as Architectural Exclusion, purposely separated African Americans and Caucasians in Atlanta. Highways were built purposely as to create a barrier between African American and Caucasian communities. These highways were built on top of traditionally African American communities, which again forced many out of their homes and farther out into the underdeveloped suburbs. These highways conveniently blocked access to the city from outlying African American neighborhoods (Sherman 14). Public Transportation routes were also built to only travel so far, and often denied certain groups access to certain destinations, such as African Americans not being able to access exclusive, mainly upper class Caucasian locations such as country clubs, high end restaurants, and gated communities through public transportation (Sherman 31). Homes continued to be destroyed by the construction of the MARTA transportation routes and forced citizens to find new homes away from the public transportation. After MARTA was built and the refugees moved further into the suburbs, city officials promised Atlanta an extension of the MARTA lines to these outlying areas, but the extensions were never built (Sherman 40). These types of architectural exclusion assisted in the African American population to be mass exiled out into the suburbs far away from the new developments in the city and quick expanding largely Caucasian communities.

African Americans have been historically racially discriminated against since post WWII. Specific groups were formed in order to make African Americans feel unsafe and unwelcome in Atlanta. The Ku Klux Klan, or KKK, for example, came together after the Civil War, and although it was disbanded multiple times, the group continued to fight for their idea of white supremacy. In the early 1900’s, Atlanta became the headquarters for the KKK and held multiple rallies in places such as Stone Mountain. The group attacked and murdered hundreds of African Americans by having their home, land, and possessions seized, lynched, shot, beaten, raped and even burned alive (Lay). During this time, African Americans constantly feared for their lives. Even after the KKK was officially disbanded, African Americans still felt threatened by members of the hate group. More than one thousand African Americans fled during these violent years and vowed to never return (Lay). This flight contributed to a larger percentage of whites populated in Atlanta, as well as it added to the already tense differences of Caucasians and African Americans. A select few eventually began to venture back to Atlanta and it’s surrounding areas, but they still carried the fear and stigma of the KKK and created a large separation from any Caucasians, which further created even more severely segregated communities.

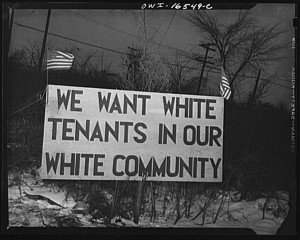

After the KKK was long gone during the twentieth century, as well as being physically forced out of their homes by developers, African Americans were psychologically forced to feel unwelcome in areas deemed dominantly Caucasian communities. This lead to more citizens being settled in separate communities due to the still existing racism. Some property owners used “racial steering”, an illegal practice which pushed away African Americans and brought in Caucasians to their neighborhoods (Riley 3). This photograph is an example of racial steering, where a billboard being held up reads that they only “want white tenants in [their] white community” (Riley 3).

A study was conducted in Detroit by the University of Michigan in 1976 that concluded that 72% of “whites” strongly opposed living in a “mixed community” with “blacks” (Farley 321). When the researchers asked African Americans why they would not move into a mainly “white” neighborhood, 90% said that it was because their Caucasian neighbors would not welcome them (Farley 322). Since a large majority was in agreement in this study, it can be applied to the city of Atlanta by having made an assumption that Caucasians and African Americans in Atlanta most likely felt the same way as those in Detroit did. The study confirmed the amount of remaining prejudice against African Americans in Atlanta as well as how effective methods like racial steering were in an attempt to reject African Americans from Caucasian communities.

In addition to having African Americans exiled from where they resided, Caucasians often choose to move away from areas already heavily populated with African Americans because of the increased gap between lower-class African Americans and middle-upper class Caucasians in Atlanta (Pooley). The Atlanta Tribune Magazine reported that African Americans are “two times more likely to be jobless” as well as “three times more likely to be poor” (Bullard 2). Private development and architectural exclusion helped widen this economic gap. Because African Americans were pushed out of the city during the development, it became difficult to find jobs in order for them to improve their economic circumstances. The magazine stated that 24% of African Americans do not own a car. This meant that without access to public transportation or another way to travel to and from the city easily, these people must be able to walk to their place of employment (Bullard 2). This is a nearly impossible feat for those who live outside of the city where a majority of jobs are located in the downtown area. Caucasians do not want to associate themselves closely with things they deem negatively and below them, such as unemployment and poverty. People naturally settle near others culturally and economically similar to them because of the comfort and familiarity of being with people just like yourself. Because these two group’s gap is so large and they hold so many differences, it is assumed that they would not naturally have chosen to live in close proximity to each other.

In addition to this economic gap, Caucasians chose to settle away from African Americans because African Americans are strongly associated with increased poverty, increased crime, and decreased home values (Poister 51). People strongly opposed having their families live and grow up close to these criminal like people in fear that it might a negative impact on their day to day lives. They fear bad habits might be picked up by their children from the lower-class children, such as school being skipped, or that their neighborhood could become less safe because the occupancy of African Americans in their community brought up crime rates.

Because African Americans have been excluded physically from the inner city on account of major development, preservation of historical areas, as well as fear, nonacceptance, and prejudice due to the action of Caucasians, Caucasians continue to settle together in their own middle-upper class communities, while African Americans congregate together in neighborhoods farther out away from the main attractions of Atlanta. If officials in Atlanta had taken into consideration the African American community before developing a large business and tourist city with various different attractions and ways to get around, African Americans might have developed in a totally different way. Where they live, who they closely associate with, and what areas they spend most of their time have the potential to be completely different if Atlanta’s environment had been built in a different way. Unfortunately, because of how the city was developed, the segregation will continue until Caucasians are able to accept the African American community and let them into their lives as being equal.

Works Cited

Bullard, Robert. “{Complete Report} The State of Black Atlanta 2010.” Atlanta Tribune The Magazine. Web. 29 Mar. 2016.

Farley, Reynolds. “Chocolate City, Vanilla Suburbs: Will the Trend toward Racially Separate Communities Continue?” Social Science Research 4 (1978): 319-44. Web.

Holliman, Irene V. “From ‘Crackertown’ to the ‘ATL’: Race, Urban Renewal, and the Re-making of Downtown Atlanta, 1945-2000.”University of Georgia (2010). n. pag. Web. 1 March 2016.

Lay, Shawn. “Ku Klux Klan in the 20th Century.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 15 October 2015. Wrb. 25 April 2016.

Newman, Harvey K. “Race and the Tourist Bubble in Downtown Atlanta.” Urban Affairs Review3 (2002): 301-21. Web.

Poister, Theodore H. “Transit-Related Crime In Suburban Areas.” Journal of Urban Affairs 1 (1996): 63-75. Web.

Pooley, Karen. “Segregation’s New Geography: The Atlanta Metro Region, Race, and the Declining Prospects for Upward Mobility.” Southern Spaces. Web. 29 Mar. 2016.

Riley, Ricky. “10 Ways Segregation and Economic Depravity Defined Chicago – Atlanta Black Star.” Atlanta Black Star. 2015. Web. 29 Mar. 2016.

Sherman, Bradford P. “Racial Bias and Interstate Highway Planning: A Mixed Methods Approach.” College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal (2014): n. pag. Web. 1 March 2016.