This seemingly weightless object reflects an equivalent color as that of the golden glow from the rising sun. Measuring 24 cm long and 2 ½ cm wide, a long rectangular object feels smooth on one side and rough on the other. A closer look reveals that this aureate fabric is formed with a satin weave in which the threads of polyester intersect to purposely create a smooth, lustrous on the front surface and a dull, matte back.

Side stitching is noticeable on each side of the fabric’s width but on each end of the fabric’s length exists frays. With one simple pull on one of these frays, the fabric will quickly and easily unravel, which discloses the object’s delicacy.

Side stitching is noticeable on each side of the fabric’s width but on each end of the fabric’s length exists frays. With one simple pull on one of these frays, the fabric will quickly and easily unravel, which discloses the object’s delicacy.

Four tiny pin holes are visible on the fabric, two of which appear approximately 6 cm from each end indicating that these two tiny holes were created by the same pin. Metamorphosing the object to have the two pin holes from each end align, the fabric crosses and the object acquires a new form. When viewed from the top, which is above the pinholes and crossing fabric, the loop of the object creates a flowing loop with no sharp turns. Two equal lengths of fabric create an upside down “v” shape that dangles below the loop, pinholes, and crossing fabric.

Four tiny pin holes are visible on the fabric, two of which appear approximately 6 cm from each end indicating that these two tiny holes were created by the same pin. Metamorphosing the object to have the two pin holes from each end align, the fabric crosses and the object acquires a new form. When viewed from the top, which is above the pinholes and crossing fabric, the loop of the object creates a flowing loop with no sharp turns. Two equal lengths of fabric create an upside down “v” shape that dangles below the loop, pinholes, and crossing fabric.

According to Robert Friedel in his essay, Some Matters of Substance, “Everything is made from something [and] the making of anything requires that choices be made about the stuff that goes into it. There are a number of grounds for these choices, of which the following seem to be…important: Function, Style, Tradition, and Fashion.”

Visually, color is the initial feature that is noticed, which suggests it holds substantial significance in choosing this exclusive object. The fact that the color is solid implies there is relevance in the isolation. It is also important to note that the shade of the object is not yellow but gold whereby gold is often darker and glossier than compared to the primary color yellow. Additionally, the shade of gold reflects a sense of complexity and depth.

Considering the satin-weave, side stitching, and frays, it can be presumed that care and precision were significant when creating this object. The fact that the object is fabricated using a delicate technique and material suggests that this aureate object serves an aesthetic purpose and is intended to be worn. More specifically, the small size suggests that the object is not used for covering things up; therefore, reveals that there is an intentional purpose for display. Likewise, the pinholes further suggests intentional display and we can consequently determine that the object’s function may be used as a brooch.

The fact that the object has to be manipulated to obtain this shape suggests that the importance of the shape is only second to the set color. At this point we can safely say that the object’s material and function were deliberately manufactured to be a fashion instrument. The color and transformed shape juxtaposed with the object’s material and function, however, insinuates the object was purposely designed to be worn as a sign.

When we compared the shading difference between yellow and gold, we notice a similarity to the satin-weave material. Gold is a darker, glossier shade of yellow and the material is purposely threaded to create glossy front; thus, was the material selected specifically for the color? If so, this would indicate that the color holds a higher importance than originally judged.

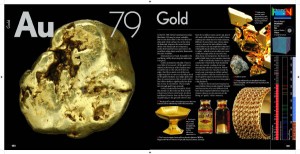

“For a variety of reasons people come to make associations between a material and various feelings, concerns, and attitudes. These associations are rarely stated, but they are quite significant to our understanding of the past and its influence on the present.” And as Friedel claims, “It is actually the question of the relationship between materials and values that is at the heart of this subject;” thus the reason for exploring the element gold in relation to the color of this object. Known as a precious metal, gold is highly valuable because of its chemical and physical properties in addition to its scarcity. History reminds us of wars about people and cultures dying to protect or obtain it or to expand beliefs/societies/land because of it. Do these experiences alter or attribute to the meaningful value placed on gold? But if we set aside the monetary and scientific worth to only consider gold’s obvious feature, its beauty, do we actually treasure its aesthetic value?

Manipulating the object’s shape arouses various speculations when we draw from the previous deductions. First and foremost, pinning the fabric together so that the four pinholes perfectly align, the shape is similar to that of the Ichthys yet without a profound, pointed loop and more fabric dangling below the pin.

Derived from the Greek word for fish, the Ichthys is commonly known as the Christian Fish or Jesus Fish and an ancientpagan symbol used as a visual expression of identification with a specific group of people. However, the position of the pinholes suggest that, unlike that of the Ichthys, this particular object is to be represented vertically. Is there a connection and/or religious undertone to this object and the Ichthys? Jules Prown claims in his Essay, Style as Evidence, “The manifestations of identical elements of style…cannot be considered coincidence: clearly cultural preferences were being expressed. And stylistic shifts…mark a change in cultural values.” But perhaps the only correlation is the method of associating one’s self with a particular group through an “artistic sign.” Prown explains that an artistic sign is “does not pertain to things but a certain attitude toward things.”

Jacques Maquet explores the meaning of objects and what they stand for in his essay, Objects as Instruments, Objects as Signs. Maquet employs us to move beyond simply interpreting objects for their role and function by reading “objects as signs” for their connotative meaning, such as symbols, images, referents, and indicators. Given that “[The meaning of an object] is grounded in common human experiences and given by the group of people to whom the object is relevant,” Maquet believes that it is difficult to derive meaning from objects because meanings are not “culture-specific,” “inherent to the object, or ascribed by the designer” and thus meanings are implicit and always changing.

The gold color and transformed shape seem to be the two most notable physical features of this object; so should these characteristics be read together or separately in order to derive the correct association and meaning? Is color deemed as an actual object or a way to read an object just as Maquet suggests (i.e. referent)? What meanings and values are attached to this object, what group of people gathered the consensus to build these meanings and values, and what human experience grounded these meanings and values?

Kenneth Haltman describes signs as a complex interrelationship between objects and their meaning. He further explains that it is not only important to concern ourselves with what the object signifies but with how the object symbolically expresses meanings and values.

James Deetz’s, “In Small Things Forgotten,” placed significance on the historical analysis of objects in material culture studies. It is through the ‘small things forgotten’ that we can “fill in the cracks between large historical events and depict the intricacies of daily life.”

Today, the gold element is commonly associated with wealth in forms of currency (i.e. money and coins) and jewelry. In reflecting upon the past, it is apparent little has changed regarding what gold signifies but it is relevant to not on how gold signifies has transformed.

For example, Ancient Egyptians believed gold held a magical potency containing significant religious properties, mostly due to gold’s corrosion-resistance element. However, they revered gold as the “Flesh of the Gods” because of its color resemblance to the sun to which they credited to the powers of the sun god.

Elaborate death rituals, the most famous is the tomb, coffins, and death mask of King Tutankhamun, substantiates that Ancient Egyptians considered gold not only as a highly prized commodity but more importantly, as a symbol of eternal life.

History, it seems, continues to influence our present whereby gold is still viewed as a symbols of wealth (owned by both rich and poor), money (standard for many currencies), treasure (pirates & leprechauns), perfection (“golden mean,” “golden ratio,” and “golden rule”), and achievement (symbol for the highest medal or award).

A concept that is important to note is how Friedel centered his studies on the material in material culture. He emphasized the significance of the “first element” to which we should consider in order thoroughly study and comprehend things – “the matter of stuff that makes up a thing”—the material. In essence, it is “not only the form [of the object] but also the [material itself which] conveys messages to us.” Therefore it would be erroneous, according to Friedel, to exclude the material itself, which is the satin-weave.

The satin-weave is a special weaving technique that has been used since ancient times and rumored to have derived from ancient China. Originally comprised of fine silk up until the invention of synthetic fibers such as polyester, the satin-weave is associated with romance and luxury. Likewise to the scarcity of gold, satin materials were limited to those of nobility, upper class, and church. Additionally, satin-weaving was viewed as a “treasured secret” but eventually this skill broadened and reached America by the late Renaissance. By the late 1800s, satin fabrics were no longer only worn by those of the upper class and was sewn into anything from bridal gowns to lingerie. In the 1920s, satin material became increasing popular and widely affordable due to the invention of artificial silk, or better known as synthetic fibers. The associations to satin that were once sacred are now viewed by some as “profane” due to the rising popularity of satin material and its public display of undergarments, lingerie, corsets, brassieres, and camisoles. According to fashion journals, on the other hand, popularity has begun to associate of satin to sensuousness and lustrous.

A conceptual context refers to the creator’s mind…the physical refers here to the association of the object out of its original, conceptual context as it moves from producer to consumer, out of the workshop and into its use context. In other words, after an object is created it moves into a new realm, both spatial and temporal, as it becomes associated with other objects and a social world of individuals who possess the object. In that sense the focus is not on the thing, the artifact, but on its makers and users as a window into social relations. It is as ‘things-in-motions’ within the context of the social place of the artisans and users that the analysis derives its meaning.

The ribbon, which we can now refer to since our analysis of it is complete, is not a sign “to be read but a story to be told or unfolded about the social impact of the actions of people and their manipulations of objects through space and time” (Rita P Wright, Technological Styles: Transforming a Natural Material into a Cultural Object). The following stages of the ribbon’s life is essential to explain, inform, and describe how the ribbon morphed into cultural object: conception, material selection, design, manufacture, distribution, use, and perception.

Strips of cloth, originally dubbed “bands,” were found from a Turkish archaeological site of Çatal Hüyük, which can be dated back to the 6th millennium. It is suggested that these “warp-faced plain weave bands” may have been used more for decorative purposes, “to ornament and trim garments.” The silk ribbons began to appear during the 11th century and became a more frequent fashion accessory throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. However, it wasn’t until the 17th century, when French King Louis XIV became obsessed with ribbons. He adorned “ribbons of gold and silver to hats, sword handles, shoes, sleeves, around the knees, and even to the lower bodice front, where yards of ribbon loops emphasized the wearer’s masculinity.”