Death: It’s a Human Condition

Last night, I kept a tradition and sang, “Happy Birthday,” to an empty chair that should contain my would-be 7-year-old son. Following an emotional night, I subsequently attended the funeral of my son’s friend, a brave 7-year-old boy also taken too soon. Death and the reminder of mortality surrounded me as I prepared this blog post.

Last night, I kept a tradition and sang, “Happy Birthday,” to an empty chair that should contain my would-be 7-year-old son. Following an emotional night, I subsequently attended the funeral of my son’s friend, a brave 7-year-old boy also taken too soon. Death and the reminder of mortality surrounded me as I prepared this blog post.

Everlasting Molds

Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and even Beethoven from Luke A. Fidler’s essay, “Impressions From the Face of a Corpse,” have something in common: immortality. Although U.S. coins featuring dead presidents are not of human bone or flesh worthy for cabinets of curiosity, they could be collected if deemed rare. Additionally, Americans almost daily handle these inanimate objects, depicting the face of the deceased in the palm of their hands and exchange them freely, without a given thought.

Death masks, however, are vastly different than that of embedded faces on metal because they are “impressions from the face of a corpse.” There are many myths mentioned in Fidler’s essay behind this popular ritual of the dead, dating back to Alexander the Great, “thanks to the assumption that it was a portrait par excellence.”

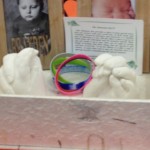

Comparable to the three-dimensional molds taken of the face of a corpse, many bereaved parents cast their dead child’s hands or feet immediately proceeding death.

Comparable to the three-dimensional molds taken of the face of a corpse, many bereaved parents cast their dead child’s hands or feet immediately proceeding death.

“Do This In Remembrance Of Me”

The rituals I created to remember my spunky son are all done to help me cope; thus rituals and traditions are established by the living as a way to grieve our survival. Objects left behind by loved ones are cherished and to evoke memories not to be forgotten. Similar to Belk’s claim, “people seek to assure that their selves will extend beyond their deaths,” I seek to keep my son’s “self” alive through photographs, traditions, toys he left behind, his sister, myself, and, of course, the foundation established in his name.

Something neglected to be mentioned in Fidler’s essays is the belief that death masks were made as an object of reflection to remember a lost loved one. In contrast, when Christians manifested, they considered a corpse to be impure and therefore, rituals for the deceased did not occur until after the growth of the religion. The prominent ritual of Christians is that of Holy Communion (Also known as The Eucharist or transubstantiation) whereby the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ is symbolically ingested.

As you’re waiting for this food, you may hear a voice saying, “Don’t look now, but you’re in this thing pretty deep. You could end up as a corpse, as dead as Jesus.”

Hence, this is where the controversy lies among many and question if the elements of bread and wine indeed “miraculously change” to the Body and Blood of Christ. Through transubstantiation, a supernatural form of Endocannibalism, Christ lives forever.

In comparison of the Christian’s ritual, eating death is taken literally in other cultures. For instance, in the British-Isles, bread is placed on top of the deceased for a period of time and then consumed by a “sin-eater” for an insulting “fee of sixpence.” It is believed that in doing this, the sins of the deceased would be passed to the bread from the corpse, which would ultimately destroy those sins by ingestion.

Painful Sorrow

The emotions of mourning the loss of a loved one can be described as painful but for the Dani Tribe from Papua, Indonesia, it is also a physical pain. Tribe members would cut off the tips of their fingers “as a way of displaying their grief at funeral ceremonies [and] symbolizing the suffering and pain due to the loss of a loved one.” This could also function as continuous reminder of the loved one lost (as if the devastation from the loss itself isn’t enough). Thankfully, this ritual is no longer practiced.

“Ashes to Ashes”

“By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.” ~Genesis 3:19

My son was cremated and I have a locket that holds some of his ashes. Many view this trinket as morbid and/or eerie. To me, however, this is a manner to keep him constantly with me. And his foundation is, hopefully, the way he will live forever. Ensuring his memory will go on is a vital comfort as my life on Earth continues.

My son was cremated and I have a locket that holds some of his ashes. Many view this trinket as morbid and/or eerie. To me, however, this is a manner to keep him constantly with me. And his foundation is, hopefully, the way he will live forever. Ensuring his memory will go on is a vital comfort as my life on Earth continues.

First off let me just say wow, what a compelling post. While I am deeply saddened to hear of your loss, I find it very admirable that you could weave your personal experience into this post. All of your examples, whether personal or otherwise, are very insightful and really assisted me in grasping the multitude of ways humans respond to, and embody death in various societies. Furthermore, it seems to be that ( because we are not likely to just “forget” something which has died) mankind’s embrace of dead objects stems not necessarily from wanting to maintain the memory of something, but to use said objects to help us understand life’s affect on us, and its eventual end. It seems that whether it be through death masks, cremation, taxidermy, or even characterization of death (via sickles, skull+crossbones, tombstones), we are so willing choose to personify death through our objects, because we have accepted its inevitable role in our lives.

Additionally, your example of coins being a kind of “death mask” that we carry with us daily, actually made me incredibly curious on the subject and inspired me to do a little more research on the subject. If you have an opportunity, I encourage you to look up (My computer is not allowing me to post links) L’Inconnue de la Seine, perhaps one of the most iconic, yet overlooked, death masks in human history. Apparently, after her drowned body was recovered, the pathologist found her beauty and smile (often compared to that of the Mona Lisa) to be enchanting, and created the mask in order to capture this beauty. Her looks apparently resonated with others as well: casts of her face became a “fashionable” object in late 19th century european households, and reportedly, many girls modeled themselves in her image.

While this story in itself is quite astounding, it goes even further: have you ever done CPR on a female mannequin? There’s a possibility you might have performed it on L’Inconnue de la Seine! Her cast was repurposed as the first mannequin for CPR training, and has been referred to as “the most kissed face of all time”. Pretty unique find that really drives home our morbid fascination with death.

I agree with the “Do This In Remembrance Of Me” section of your post and I think what you said is very poignant about keeping memorabilia of your son and a tradition strong . To have an item of a person no longer here seems to provide understanding of who they were as people. The item itself grows as time passes and new discoveries about that person can be made through it.

In the article about the death mask it would seem people were doing just that; a face is something truly unique that can be the closest substitute of who a person was. It is understandable that there would be cultures creating these busts because of the facial uniqueness of a person. With every “bump and groove” as Fidler put it, there is another nuance that made that person one of a kind.

The death mask seem to substitute for the ideas of a person, or the personality, or every association of that face with a loved one. We get most of our sensory information from our eyes so when we see that person through the masks, or the photographs you mentioned, we orient our other senses and memories to what we associate when we see their faces.

But on the other hand, as Fidler pointed out, some of the people found the masks grotesque. Similar to how you said some people found your locket eerie, I think it has to do with the idea Belk discussed in his article about how we identify ourselves the most (body parts being the top of the list). It is understandable both ways; we can capture a person’s identity by preserving a part of them, and through that a representation of who they were; yet, it can be viewed as literally taking a part of someone’s identity and that can disturb a person because that is how we (according to the study) most accurately identify ourselves and that can be taken.

This was a sad post and I’m very sorry about your son and his friend.