Bowen Homes was an Atlanta Public Housing development built in 1964. It was one of the last developments that was demolished in 2009. What was once one of Atlanta’s largest housing developments is now 74 acres of vacant land with only the abandoned A.D. Williams Elementary school left standing. Plans for redevelopment have been announced but work has yet to begin.

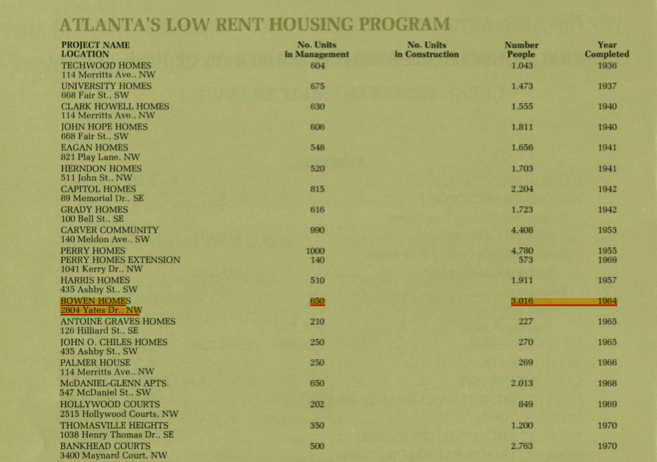

Atlanta has always been at the forefront of public housing. Dr. John Hope and Charles Palmer were eager to boost the economy and provide housing for poor Atlantans struggling with the great depression. In 1934 under the New Deal legislation laid out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the first federally funded housing projects were developed. They were known as Techwood Homes and paved the way for future public housing developments all over the city.

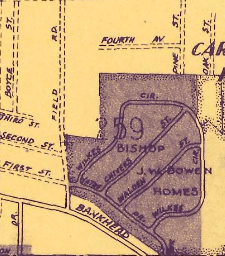

Between 1934 and 1964 over 30 different public housing developments were built all around the city. Bowen Homes was one of those developments that served west Atlanta. It sat along then named Bankhead Highway (now Donald Lee Hollowell PKWY). 104 brick buildings contained 650 residential units, a day care, an elementary school, and library. It had over 3000 residents, all African American.

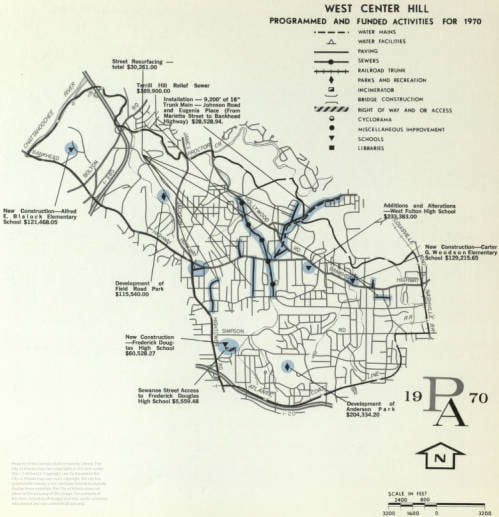

When Bowen homes first filled its units, like most public housing, it seemed promising. Residents established a tenant association and created a tight knit community.2 There was much hope that Bowen homes would provide security and a chance at upward mobility. Most of the residents were those displaced from Buttermilk Bottoms, a neighborhood in the Old Fourth Ward.3 The city invested in public services that would serve not only Bowen homes and the other nearby developments such as Perry Homes and Bankhead Courts.

Atlanta Housing Authority 19704

A series of elementary schools were built for the children of these residences. Bowen Homes was zoned for A.D. Williams elementary school, which sat across the street from Bowen Homes. There was also a day care within the development providing childcare and pre-school programs. A recreation center, sharing the same name as the elementary school, also sat just behind the elementary school. The recreation center is also home to the Police Athletic League (PAL), which provides recreational sports and outreach programs for at risk youth.

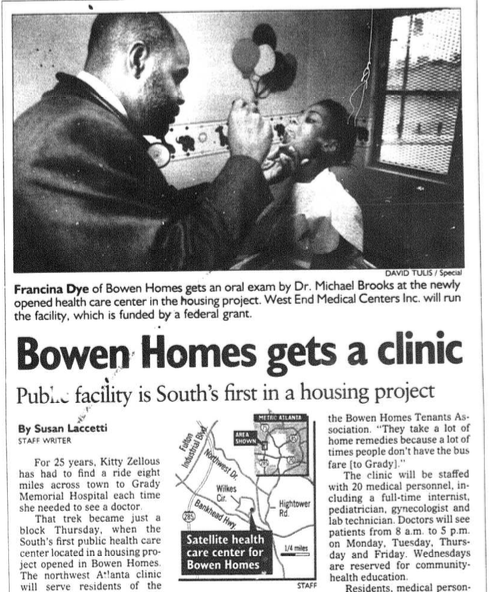

Non-government social services were also becoming available in the greater west Atlanta community. In January of 1992 the West End Medical Centers Inc. established a clinic within Bowen Homes. They received a 3 year federal grant to help fund the clinic. It was the south’s first public health care center to be opened in a public housing development.6

For as much positivity and promise that was shown with the establishment of Bowen Homes, there were also significant draw backs. Atlanta was still very much feeling the effects of Jim crow, and the housing itself was subpar. Most, if not all, of the residents were living in poverty.

Although public housing was federally funded, the funds only covered initial construction. This left the cost of maintenance and repair to the city. With so many housing developments around the city and no actual revenue being generated from the units rented out, there were little resources available for upkeep of these properties. Consequently, the condition of the housing units quickly deteriorated.

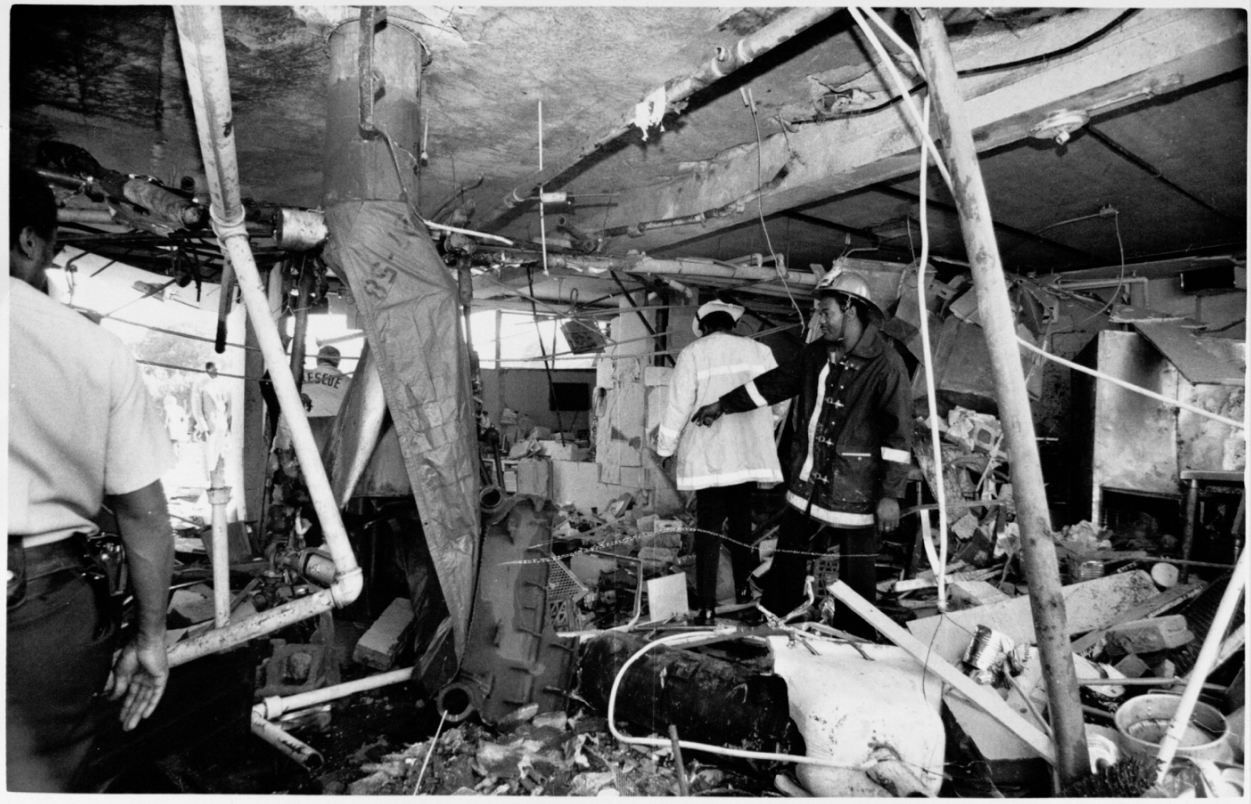

In October 1980, the community suffered one of the most traumatic events in its history. A gas water heater exploded in the day care, killing 5 people, 1 teacher and 4 children. Fire officials determined that the explosion was due to a faulty boiler that was drained and never refilled. A.D. Williams Elementary received a bomb threat the same day as the explosion, prompting residents to suspect that foul play was involved.8

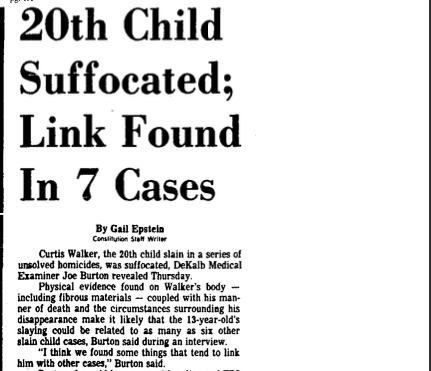

There was also a string of over 20 child murders in the city that spread fear throughout the community. Most famously was that of Curtis Walker, 13-year-old boy who went missing in February of 1981. He lived on the same street as the day care center with his mother and 6 siblings. His body was found almost a month later in Dekalb County. Walker’s case like most of the cases, is attributed to Wayne Williams but is still unsolved to this day. 10

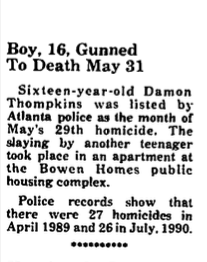

Much like the conditions of housing were declining, societal changes were influencing and contributing to Bowen Homes’ overall deterioration. An increase in crime in the area began to find its way into the community. The influx of drugs into the city increased the impact. The traumatic events of the 1980s, marked a shift in the housing community.

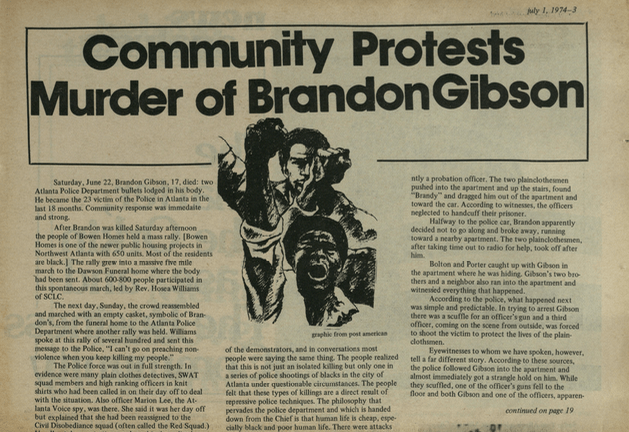

Still dealing with the effects of Jim crow, redlining and other forms of racial oppression, tensions were high between the community and law enforcement. There were killings of residents by Atlanta police, causing continued civil unrest. Drugs and crime became the new norm. The development became an eye sore for the city.

In 1994, the Atlanta Housing Authority decided to get rid of public housing in the city and replace them with mixed income communities. There was cause for concern from the residents regarding displacement. Once again with the assistance of another federal grant program known as HOPE VI, the housing authority began demolishing the developments. Residents were offered a voucher to live in the mixed income developments or the option to move to a different public housing development.11

In 2009 Bowen Homes, was finally demolished.12 Around 1300 residents were displaced and either moved to different public housing developments still available or relocated to the mixed income communities. This marked the last large scale public housing property in the city.

By 2011, all the properties had been torn down. Once again, Atlanta was at the forefront becoming the first city in the country to do away with all its public housing completely.13

As of today, the 74 acres where Bowen Homes once stood is still vacant land. Since the demolition, the community has continued to decline. Those who could not find housing became homeless. Local business that once thrived no longer had sufficient patrons to stay open. Although there still is heavy traffic, it’s a result of people commuting to and from the city.

Plans have been made to revitalize the area. In July of 2023, the Atlanta Housing Authority and City of Atlanta announced a $40 million federal grant to help redevelop the community. It will be known as the Bowen Choice Neighborhood and is expected provide affordable housing and increase commercial activity to revitalize the entire west side of Atlanta.14The city is expecting similar investment like that of the public housing communities. There is expected to be a mixed income community, public transportation improvements and incentives for retail investment. The Atlanta housing authority is hoping to revitalize the area through both public and private investment. The anticipated cost is expected to be over $200 million. For now, the gates to Bowen Homes remain locked and like the surrounding community, it sits with nothing but hope.

- atlpp0062-26, Planning Atlanta Planning Publications Collection, Georgia State University Library. ↩︎

- Simmons, Ted. “Housing is a Way of Life–and Bowen Homes Prove it.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Dec 22, 1965. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/housing-is-way-life-bowen-homes-prove/docview/1554840521/se-2 ↩︎

- Smith, Joel W. “Atlanta Housing Authority to Open Bowen Homes in February: 650-Unit Facility Erected to Provide Relocation Housing.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-), Dec 22, 1963. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/atlanta-housing-authority-open-bowen-homes/docview/491301598/se-2 ↩︎

- West Center Hill: Programmed and Funded Activities for 1970, atlpp0217_70, Planning Atlanta City Planning Maps Collection, Georgia State University Library ↩︎

- West Center Hill: Building Conditions and Predominant Treatment, Citation: atlpp0217_69, Planning Atlanta City Planning Maps Collection, Georgia State University Library. ↩︎

- West End Medical Center Clinic, AJCP157-026z, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library ↩︎

- AHA 1983 Annual reports, atlpp0065, Planning Atlanta Planning Publications Collection, Georgia State University Library. ↩︎

- King, Barry and T L Wells Constitution,Staff Writers. “Four Children, Teacher Die in Explosion at Day Nursery: Blast Levels Classroom and Kitchen.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Oct 14, 1980. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/four-children-teacher-die-explosion-at-day/docview/1644081669/se-2 ↩︎

- Firemen sorting through debris Citation: AJCP157-026y, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library ↩︎

- Gail Epstein Constitution, Staff Writer. “20th Child Suffocated; Link found in 7 Cases.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Mar 13, 1981. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/20th-child-suffocated-link-found-7-cases/docview/1614147377/se-2. ↩︎

- Hankins, Katherine, Mechelle Puckett, Deirdre Oakley, and Erin Ruel. “Forced Mobility: The Relocation of Public-Housing Residents in Atlanta.” Environment & Planning A 46, no. 12 (December 2014): 2932–49. doi:10.1068/a45742. ↩︎

- https://www.ajc.com/news/local/bulldozers-begin-razing-bowen-homes-housing-project/QjEyV2jJqNlLdu4iWDVgBL/# ↩︎

- Goetz, Edward G. “The Audacity of HOPE VI: Discourse and the Dismantling of Public Housing.” Cities 35 (December 1, 2013): 342–48. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.008 ↩︎

- https://www.atlantahousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Bowen_CN_Transformation_Plan8.pdf ↩︎