Argentina’s turbulent history during the military dictatorship left deep scars on the nation’s collective memory. A visit to La Perla, a notorious site of torture and murder during the Dirty War in Argentina, shed light on the deep impact of the suffering there and the resilience following the human rights violations.

The body has memory

I translate this quote as the following:

“The body has memory, traces, marks that are there, that appear if called upon. Even if we do not think of them, the body reacts by bringing them forth. Memory surrounds, permeates, from the inside and outside.”

Photographs commemorating women who were killed at La Perla

This evocative quote, hung on a flag commemorating the many women whose lives were taken at La Perla, encapsulates the idea that the body itself carries the weight of traumatic memory. Even when forgotten or suppressed, it lives on in the body. The quote reflects the profound connection between memory and the physical self, highlighting the deep impact of trauma on individuals. For me, this quote evoked the salience of epigenetics. Broadly, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that can occur without alterations in the underlying DNA sequence. It explains how environmental factors– such as traumatic experiences– can impact gene expression and, subsequently, influence physical and mental health outcomes.

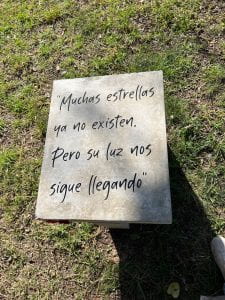

“Many stars no longer exist. But their light keeps reaching us.”

The notion that the body carries memory and that it reacts by bringing forth these memories aligns with the idea that trauma can leave lasting imprints on an individual’s epigenome. These epigenetic changes can occur not only in the individual who experienced the trauma directly but also in their germ cells, which are responsible for passing genetic information to future generations. The quote’s emphasis on the body’s memory and the notion that memory surrounds and permeates from the inside and outside coalesces with the idea that trauma can leave an indelible mark on future generations. Put simply, women who endure trauma can physiologically pass this experience of trauma onto their offspring.

Mary R. Harvey (2007) explores the sources and expressions of resilience among trauma survivors. While not specific to Argentina, the concepts that Harvey presents offer insight into the strength and adaptability of individuals who have faced immense adversity such as the women in La Perla. The article examines the individual characteristics, social support systems, coping mechanisms, and personal beliefs that contribute to resilience. It reveals how trauma survivors can harness their inner strength and create a sense of purpose and meaning.

Resilience as explored by Harvey offers a glimmer of hope. It demonstrates the inherent strength of people; it explains people’s capacity to heal, rebuild, and transcend the oppressive legacy of intergenerational trauma. The resilience exhibited by survivors of atrocities, including those who survived the horrors of La Perla, exemplifies the indomitable spirit of humans.

Reconciling Harvey’s article with the above quote and the experiences of those in La Perla, for me, evokes the multidimensionality of trauma and resilience. It invites us to reflect on the interplay between memory, trauma, inherited experiences, and the human capacity to overcome and thrive. As we as students work to strive for a better future, it is vital for us to acknowledge both the suffering and the resilience of survivors.

A memorial needs to be visually impactful

A memorial needs to be visually impactful