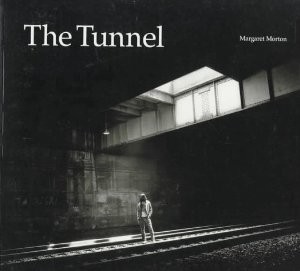

Nersessova’s article, Tapestry of Space: Domestic Architecture and Underground Communities in Margaret Morton’s Photography of a Forgotten New York, is a literary analysis of Morton’s book The Tunnel: The Underground Homeless of New York City”. In this article, she examines the pictures and stories of homeless people in Morton’s book as a way to interpret urban life and the human psyche. She argues that a person’s house is an imperative part of themselves and that its fleetingness affects us greatly, saying: “Because shelter is an essential part of sustaining oneself, identity is closely tied to one’s place of home, and because no place is guaranteed to be a permanent home, this aspect of identity is consistently fragile” (Nersessova). She then goes on to make a point that though the shelters of the homeless are more at risk, no one’s home is permanent.

When taking photographs of others, one must be careful of the intent behind them to not erase the subject’s own story. Nersessova analyzes Morton’s photos with the concept of dérive. She goes on to explain the history of that term, writing: “The precursor of the dérive is flânerie. The flâneur, or one who practices flânerie, is a mercurial character, who plays roles ranging from a dandy stroller to a careful observer who studies social space” (Nersessova). The difference between a flâneur and a dérive is that the flâneur involves a picturesque stroll and an interpretation of their surroundings based on that, while the dérive is just an everyday person walking through their surroundings. Morton therefore takes the pictures as they are, attaching no other meanings to them.

Nersessova makes a point to say that the building of the houses in the tunnel is a form of art. The residents are expressing a part of themselves to their community and the world at large. This in turn brings them closer to each other, allowing for a sense of community and safeness. She paints the tunnel as a sort of escape for people both mentally and physically. It allows its residents a peace of mind and a place to hide from the aboveground world and problems within it.

Though the tunnel offers shelter to the homeless, it is not a stable life. They construct their houses, only to find themselves locked out of the tunnels by the city. They are accused of trespassing and could get in legal trouble if they continue living there. Nersessova makes a point that this is more similar to the general public than we would like to admit. Our homes are also fragile things that can be taken away the moment something goes wrong. Though we see ourselves as very different, it is a common problem that both the homeless and people with homes share, but something the homeless are more acutely aware of.

NERSESSOVA, IRINA. “Tapestry Of Space: Domestic Architecture And Underground Communities In Margaret Morton’s Photography Of A Forgotten New York.” Disclosure 23 (2014): 26. Advanced Placement Source. Web. 20 Nov. 2015