My son is nine, and he loves Grand Theft Auto (GTA). Now, before you start condemning me as a bad parent and scolding me about how I shouldn’t let my son play a game clearly designed for older players, hear me out. My son is the seventh of eight boys. In other words, the game was purchased for older players, but they have since aged-out of my house and left for college and life. So, what we have is a legacy game, a game he grew up watching his brothers play–and he plays. But, if you still want to condemn me, I have to say there are a lot of other mothers and fathers out there that need condemning as well because, just in my experience listening on the other end of the game (and I do listen!), I have heard him play with scores of kids his age and younger. So, now that we have that out in the open, we can be honest with one another. I’m not going to pretend I keep my kid away from anything other than “E”-rated games, and you are not going to pretend like I’m the only parent doing this.

GTA is such an expansive game that, like life, it offers my son a lot of choices–but unlike life, I can sit on the couch behind him, watch what he does, and hear what he says.

GTA is such an expansive game that, like life, it offers my son a lot of choices–but unlike life, I can sit on the couch behind him, watch what he does, and hear what he says.

I don’t do this all the time (I have a life), but I do it often enough that I have started to critically analyse what my son does in-game. I know you will be skeptical, but I propose that GTA is one of the most educational games out there–and not the type of education most attribute to the game.

Before I get to the amazing skills my son has developed through GTA, I will start with the basics so you have an idea of his set-up, his level, and the general way in which we allow gaming in our house. We’ll start with the environment he games in: We have an aging XBox 360 in a family room. It’s a fairly public place, which is how I like to keep online games and computers in our house. His little brother likes to sit in there, and they switch off playing games–often without civility. None of us have a computer or a game console in our rooms, and I also discourage the use of any electronic devices in bed. (I model this behavior by turning off my addictive iPhone at 8:30 every night, and doing without until 6:30 a.m.) Although we have one XBox 360, we have two XBox Live accounts in order to permit parallel play in Minecraft, and so that brothers keep their game identities separate as much as possible. (Nothing ruins your street-cred like your seven-year-old brother playing your avatar badly.)

My son has been playing GTA in its various generations for years now–and he enjoys the expansive map available in GTA5, even though he had to give up the opportunity to play as a cop. Although he often plays online, he also enjoys some quiet repast in a solo game every once in a while to catch his breath. He is at level 115, which he assures me is pretty high. He doesn’t buy in-app purchases, so he got to that level honestly. The only real money we have shelled out for his gameplay is his new Turtle Beach microphone so that he doesn’t echo or sound weird to his fellow players. OK, that’s the basics.

My Observation of his GamePlay

I admit, I don’t play GTA. The last console game I played was Pokéman Snap on a GameCube–which tells you how long it has been; but I do enjoy the role of spectator. It’s not just GTA I watch, its also Call of Duty (I think we have 6 versions), Minecraft, and once in a while even Diablo (which I have always loved, but haven’t played as a console game). There are, of course, things that are morally repugnant in GTA–like stealing cars, shooting innocent bystanders, and robbing honest hard-working small business people–but, for the most part, it is a minor part of his gameplay. What I see him doing most is racing cars and bicycles on deviously arranged game courses that skirt the laws of the game’s physics, and searching for glitches in the game. This is his new fascination. He has played so long that it is the small errors and spots of unfinished graphical interface that fascinates him most. When he finds a new glitch (his latest was the ability to ride a bicycle up walls), he spends time perfecting his knowledge of the glitch–how much of the game does it affect (are other buildings that look similar, similarly affected)? How far can he take the glitch (can he ride all the way up the building to the roof)?, and at what point has he pushed it too far (he falls out of the game map on a pretty regular basis). He also spends a lot of time resetting GTA after particularly interesting probes into the glitches he finds.

He also spends some time organizing and joining “crews” of players who are engaged in team activities and and challenges. These are goal-based challenges that can involve anything from finding and stealing a particular type of car, to creating or participating in various races. Some of the challenges are built into the game as “missions.” Other challenges, the ones my son is mostly likely to participate in, are independent challenges designed by the gamers themselves. The motivation for undertaking missions is financial. Without the in-game money provided by racing and participation in challenges, my son cannot buy and, more importantly, customize his character’s cars and housing.

So, why does my son play this game? I think there are two major factors:

- social involvement with other gamers, and

- challenge.

Kids love a challenge. They love to be great at something, and the enjoy learning toward a goal. Yes, I know, there are plenty of “educational” games out there that are challenging, but he isn’t interested in them. Games labeled “Educational” don’t allow the same level of choice, provide the same level of social interaction, or provide the same balance between sandbox (relaxed and creative) and active (challenges and social interaction) gaming that GTA5 allows. It seems that most “educational” games are more a gamification of education than they are education through games. My friend, Frederick Cope, summed up the problem with educational gaming in an intriguing and mind-blowing way in a recent conversation. Cope said, “Educational games have education as their goal, and people disengage from goals and forget them once they have been achieved. Most people learn from function–for example, does a certain skill function to provide success? If so, they use it and remember it.” I haven’t found one stitch of academic writing on the issue of “goal based” vs “function based” education–but it is such an intriguing idea that I am hoping that someone will read about it here and go do an amazing study. Meanwhile, it simply makes sense. If my son is learning something he can use more than once (function) then he remembers it in case he needs to use it again. If he learns something he can use only once (goal) then he fails to retain it. Cope’s statement is at once non-intuitive–and true.

So, what is my son learning? I’ll start with his obsession with glitches in the game and, hopefully, you will get a sense of why I believe so strongly that he is learning a lot through his gaming.

The Search for Glitches

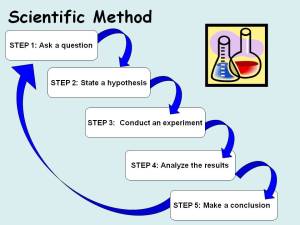

HIs interest in glitches started much the same way as my interest in academic subjects is piqued–through research. His research methods began on YouTube as he began watching his favorite gamers ply their craft in narrated recordings where they confronted some difficulty freeing a bicycle that had become merged with a jump, or found they could walk through solid concrete walls. Like any scientist, he started with an attempt to replicate the results reported in his research–tearing through the house, ejecting his brother’s Minecraft game, and feverishly looking for the exact spot the glitch took place in the video.  Once he was able to replicate the results, he began to hypothesize: If this glitch exists here, it must also exist in similar circumstances in other places in the game. He then began a grid-by-grid search, experimenting until he could replicate the glitch in a new spot in the game. He then tried to find out how far he could push the glitch. For example, in the case of walking through a wall, could he walk through all the walls in the building? Only at certain heights? Could he walk through roofs? Floors? He would try every possible combination (I suggested the term “algorithm”) until he exhausted the possibilities by either freezing the game or falling out of the game map (this is a freaky thing to watch, by the way, as his character plummets through a void with the grid of the game hanging over his head). Without realizing it, my son was deeply involved in the scientific method–which I recognized–and when I did, he began putting the academic language he had learned in his science class to use. “My hypothesis is . . . ,” this experiment showed . . . ,” and “I replicated the results by . . . . “ In this way, the scientific method he learned in school becomes a real, applicable template for what he is already doing, and his school learning is reinforced through practical application.

Once he was able to replicate the results, he began to hypothesize: If this glitch exists here, it must also exist in similar circumstances in other places in the game. He then began a grid-by-grid search, experimenting until he could replicate the glitch in a new spot in the game. He then tried to find out how far he could push the glitch. For example, in the case of walking through a wall, could he walk through all the walls in the building? Only at certain heights? Could he walk through roofs? Floors? He would try every possible combination (I suggested the term “algorithm”) until he exhausted the possibilities by either freezing the game or falling out of the game map (this is a freaky thing to watch, by the way, as his character plummets through a void with the grid of the game hanging over his head). Without realizing it, my son was deeply involved in the scientific method–which I recognized–and when I did, he began putting the academic language he had learned in his science class to use. “My hypothesis is . . . ,” this experiment showed . . . ,” and “I replicated the results by . . . . “ In this way, the scientific method he learned in school becomes a real, applicable template for what he is already doing, and his school learning is reinforced through practical application.

Lastly, he “publicized” his research by sharing his knowledge with other players, and receiving social reinforcement from his peers. It is this social aspect of gameplay which I realized was even more valuable than his strong grasp on the most basic of scientific tools.

Social and Emotional Learning

My son’s exposure to man/boy culture in my home as one of the youngest of eight boys has already matured him emotionally compared to other kids his age, but I also see that his experience in-game both in GTA5, and in Call of Duty and other first-person online experiences has prepared him well to negotiate social situations online.  He is especially adamant about the issue of “rage-quitting.” He refuses to “rage quit,” and he can’t stand it when another gamer does it, “Don’t worry about it,” he will say to another player, “It’s not important enough to get angry about. This is only a game. Keep your mind on the objective and have fun. That’s why we are here.” He often bemoans his interaction with other players his age by saying, “They are such babies! Don’t they know that this is JUST a game? Why are they so upset when they get killed? I get killed over and over and over again. It’s no big deal. You just pick yourself up and keep going.” I have heard him actually call another kid “a baby,” (which usually stops when I poke my head in the room), but more often I have heard him coaching others to be more resilient in-game. As I listen to this interaction, I can’t help but marvel at his leadership skills with other players, even players much older than he is. This is a game where age is not as important as rank, and he has earned his stripes. He takes pride in being invited to participate in crews that are far above his game-level, and he helps coach those below him (something he has learned from those above him). There is an emotional matrix in the gaming community that rewards those who keep their head and tries to encourage those without those skills to build them. It’s an apprenticeship, of sorts, and I can see that it is a healthy social environment. Not to say that he is an angel! He gets into some heated spats, but when he does, his brothers and I are there to remind him, “What did you tell that other kid? Isn’t this just a game?”

He is especially adamant about the issue of “rage-quitting.” He refuses to “rage quit,” and he can’t stand it when another gamer does it, “Don’t worry about it,” he will say to another player, “It’s not important enough to get angry about. This is only a game. Keep your mind on the objective and have fun. That’s why we are here.” He often bemoans his interaction with other players his age by saying, “They are such babies! Don’t they know that this is JUST a game? Why are they so upset when they get killed? I get killed over and over and over again. It’s no big deal. You just pick yourself up and keep going.” I have heard him actually call another kid “a baby,” (which usually stops when I poke my head in the room), but more often I have heard him coaching others to be more resilient in-game. As I listen to this interaction, I can’t help but marvel at his leadership skills with other players, even players much older than he is. This is a game where age is not as important as rank, and he has earned his stripes. He takes pride in being invited to participate in crews that are far above his game-level, and he helps coach those below him (something he has learned from those above him). There is an emotional matrix in the gaming community that rewards those who keep their head and tries to encourage those without those skills to build them. It’s an apprenticeship, of sorts, and I can see that it is a healthy social environment. Not to say that he is an angel! He gets into some heated spats, but when he does, his brothers and I are there to remind him, “What did you tell that other kid? Isn’t this just a game?”

There are times when he has been subjected to some somewhat inappropriate or scary situations online, but those are also learning experiences. Often there will be a potty-mouthed teen or young adult online (often raging because my son has just won a match or race), and although my son does participate in some soft-profanity at times (he probably does more when he knows I’m not listening), he prefers not to listen to it. “Dude, seriously! Do you have to talk like that?” This is the type of self-advocacy I love to see. He is taking control of the situation and indicating what he believes to be socially unacceptable. Similarly, he has been invited to meet other players at strip-clubs and other adult venues in-game. I have frozen in place as I prepared dinner in the kitchen, waiting for his response from the other room. “I’ll meet you outside, OK?” he said smoothly. These are all demonstrations of his ability to stand up to peer pressure. Sure, he knows that we are around, but I think that helps to reinforce his choices–and they are choices. The game allows him to participate in all sorts of adult activities, but he choses not to. I can only hope, as a parent, that he will make the same real-world choices.

He has also had some experience with hacking. First there was the hacking of XBox Live in general by the “Lizard Squad.” They constantly knocked him off-line. This was also a great learning experience, as he saw that the selfish actions of a few can really hurt everyone else. He was further infuriated when he found out that it was all done to promote Lizard Squad’s commercial ventures, and longed for a time when he could code and take down some hackers himself. There was also a somewhat scary situation with an in-game hacker known as

He has also had some experience with hacking. First there was the hacking of XBox Live in general by the “Lizard Squad.” They constantly knocked him off-line. This was also a great learning experience, as he saw that the selfish actions of a few can really hurt everyone else. He was further infuriated when he found out that it was all done to promote Lizard Squad’s commercial ventures, and longed for a time when he could code and take down some hackers himself. There was also a somewhat scary situation with an in-game hacker known as  “The Janitor,” who had taken on the identity of a legitimate GTA5 character, then appeared and disappeared, messed with people’s stuff, and played with the physics of the game. The feeling of helplessness and vulnerability my son felt during that interaction stayed with him for a long time. He asked a lot of questions about cybersecurity, how much information was available online, and whether or not someone could find out who he was and where he was. These were all learning moments, times when, as a mom, I was glad to sit down and research digital literacy with my son and teach him what he needed to know about his own digital footprint.

“The Janitor,” who had taken on the identity of a legitimate GTA5 character, then appeared and disappeared, messed with people’s stuff, and played with the physics of the game. The feeling of helplessness and vulnerability my son felt during that interaction stayed with him for a long time. He asked a lot of questions about cybersecurity, how much information was available online, and whether or not someone could find out who he was and where he was. These were all learning moments, times when, as a mom, I was glad to sit down and research digital literacy with my son and teach him what he needed to know about his own digital footprint.

Financial Issues

When I was nine, I had an idea of how much a candy bar was, and what a savings account was (I had one), but I didn’t have a clue about insurance, banking, and the world of work. My son knows all about these things through GTA5. When you buy a car, you better buy insurance, and it isn’t cheap. If you don’t buy insurance, the fine car you just purchased is destroyed, and it’s not coming back. With insurance, he doesn’t have to worry about theft or even driving straight (which is good, because he doesn’t really). He also has a job in GTA5, and if he doesn’t go, he can be fired. Without money, he can’t afford his house, his  fancy cars, or any of the food his character needs to replenish himself with. These are not real-life simulations, but they are a heck of a lot more convincing and real than any experience I had playing monopoly or “The Game of Life.” This has lead to an overall better understanding of the way the world works in real life, and he is more interested in financial issues than I would have been at his age. He also has learned the hard way to deposit and save his money toward goals–like that awesome custom paint job. If he is killed or robbed, it doesn’t matter how hard he worked–his money is gone and it isn’t coming back.

fancy cars, or any of the food his character needs to replenish himself with. These are not real-life simulations, but they are a heck of a lot more convincing and real than any experience I had playing monopoly or “The Game of Life.” This has lead to an overall better understanding of the way the world works in real life, and he is more interested in financial issues than I would have been at his age. He also has learned the hard way to deposit and save his money toward goals–like that awesome custom paint job. If he is killed or robbed, it doesn’t matter how hard he worked–his money is gone and it isn’t coming back.

Take Away’s from GTA

There are a lot of things GTA has lead my son to investigate on his own. For example, coding and game development is especially interesting to him. I have have come up on him in the office as he reveals code in his favorite YouTube Video, looking at the way it is nested and constructed. I am convinced that his gaming has lead directly to this curiosity. He’s also interested in the way in which gamer-banter and narration assists in the enjoyment of games, and he often narrates the games he plays in a way similar to his favorite YouTube gamers. This reminds me of my friends practicing the delivery of baseball play-by-plays when I was a kid–and how that lead some of them to that career. I have also noticed a more sophisticated and vivid vocabulary that my son employs on a regular basis–describing the “pearlescent” look of frost on a window–for example. The most obvious take-away from the game is what educators like to call “critical thinking.” Because of his exposure to the game, he is more likely to think through issues and analyze them in more depth than I see in his non-gameplaying friends. His visual acuity is also enhanced. Last week, I saw an accident occur, and when I later recalled it to my husband, my son corrected me: “It wasn’t a Ford, it was a Dodge. It had standard rims, it had a custom paint job, and there was some fender damage on the front drivers’ side.”