Hurt Park is a two-acre park located at 25 Courtland St SE. Opening in 1940, the park transformed “an area of rambling, obsolete and run-down structures into a rolling stretch of green lawns.”1 Named after Joel Hurt, one of the most influential people in the city’s early history, the park is now co-owned by the City of Atlanta and Georgia State University after a recent renewal. But what was the history behind the land and the man it was named after?

Looking Back

Looking in the past reveals the history that Hurt Park has been built upon. What is now a park that is central to downtown Atlanta and GSU’s campus used to be home to people and businesses.

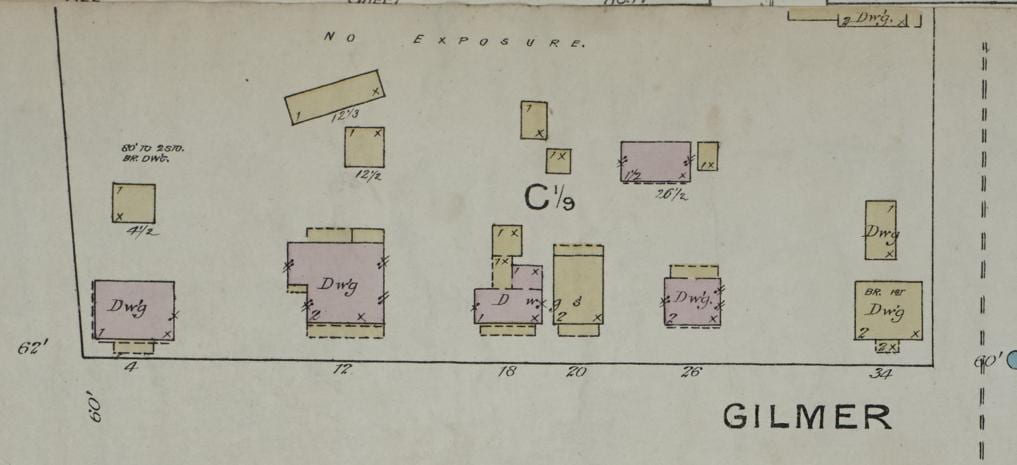

1886

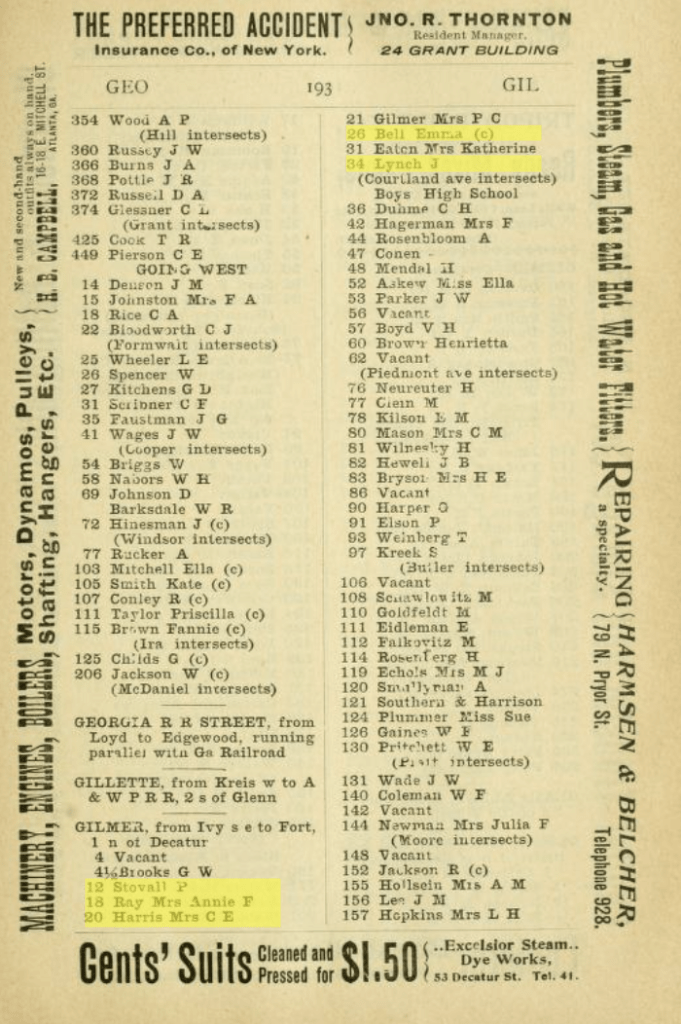

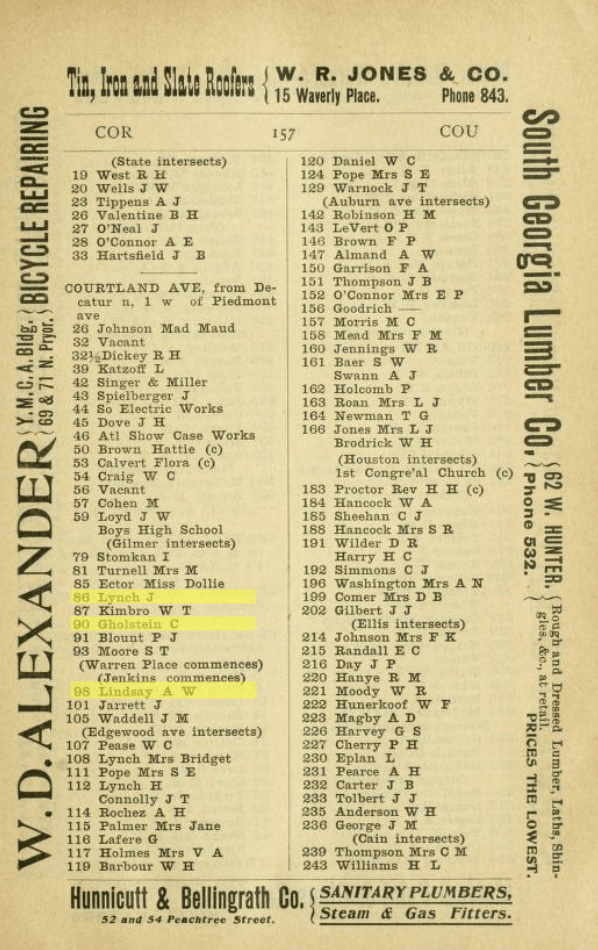

Starting in 1886, the Sanborn map reveals that this area was used as dwellings (labeled ‘Dwg’ on the map). Starting from left to right, residence 4 was a boarding house owned by Mrs. Elizabeth Monteith, residence 12 housed James and John Lynch, residence 18 was home to H.A. Smith, residence 20 was vacant, residence 26 was home to Mr. Daniel Clower, a rockmason, the rear residence of lot 34 was home to two Black laundrywomen Malvina Sheppard and Camilla Smith and another Black laborer Jackson Jenkins, the front of the house was home to the widow of John Smith.3

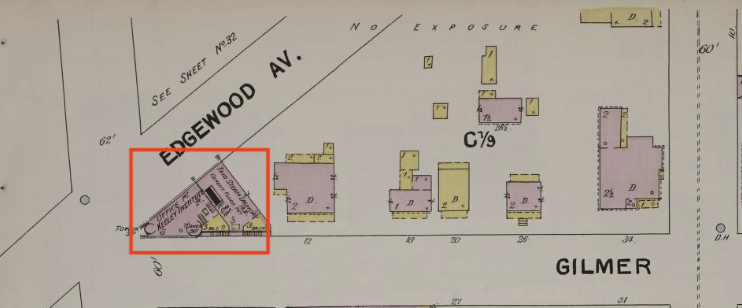

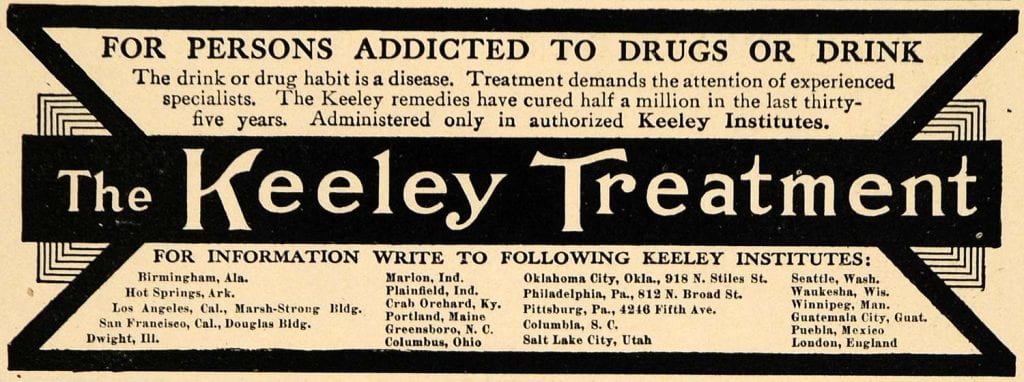

1892

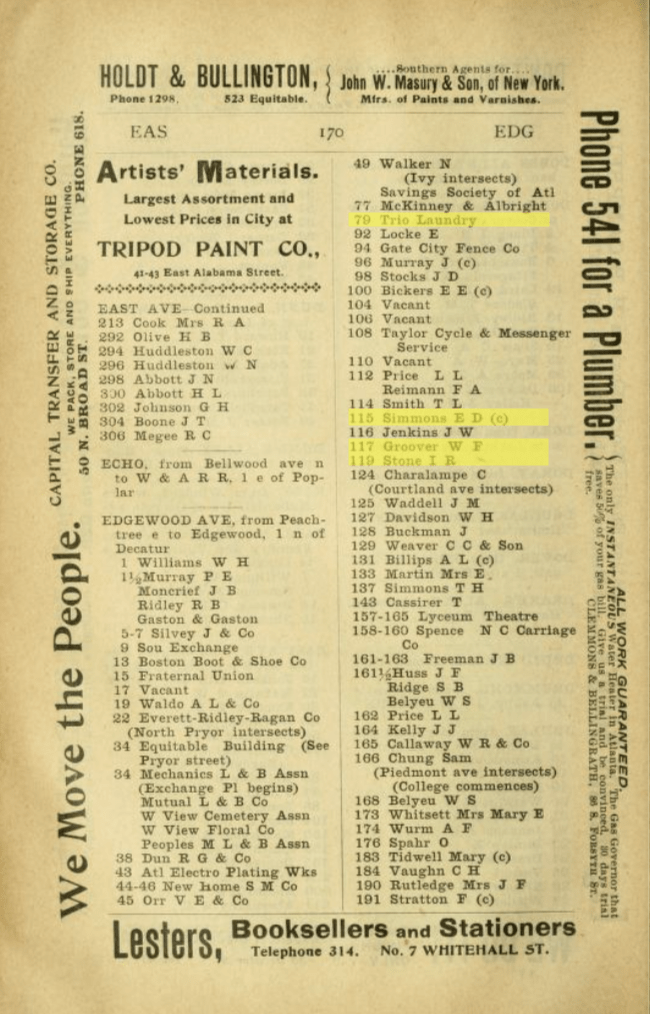

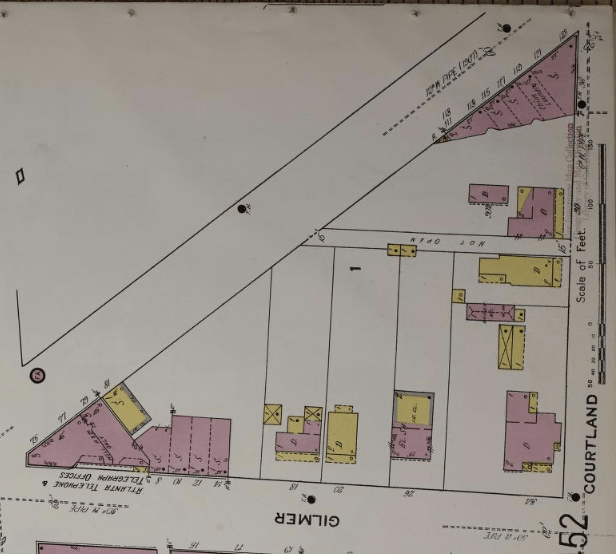

In 1892, the Sanborn Map reveals two new businesses where parcel 4 used to be in 1886. The Trio Steam Laundry was located on the corner of Gilmer St. and Edgewood Ave. According to an Atlanta Constitution article, a former employee, C. E. T. Norton, who was once a lady’s man was found missing and owed the laundry business money. The police never found him, and many of his friends believed there was foul play.5 Adjacent to the Trio Steam Laundry was the Keeley Institute, a medical institute focused on treating alcoholism. Started by Dr. Leslie E. Keeley during the Civil War, he later partnered with Frederick B. Hargreaves and together they created the “Double Chloride of Gold Remedies” to help cure inebriety. The ingredients of the Double Chloride of Gold treatment were never revealed since staff were sworn to secrecy. The branch located in Atlanta was one of the first franchises outside of the founder institute in Dwight, Illinois.6 The location of the Atlanta branch was esteemed because of its close proximity to boarding houses and hotels.7 Besides the businesses located on the corner of Gilmer and Edgewood, the other dwellings appear to have had additions. Parcels 18 and 20 remained the same, but parcels 12, 26, and 34 all changed in the 6 year jump.

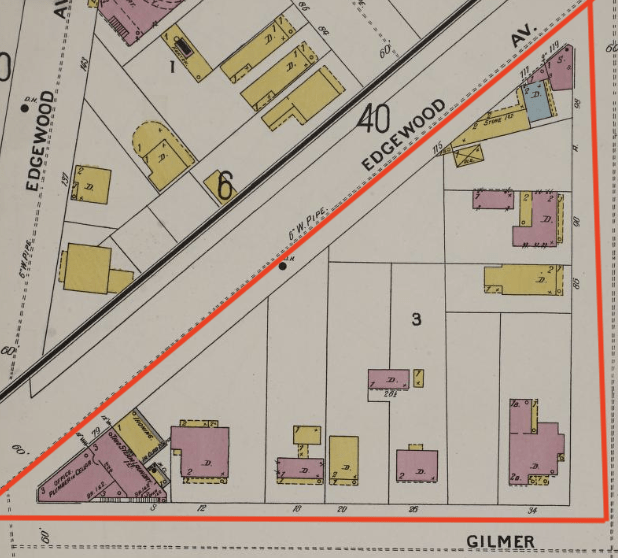

1899

The 1899 Sanborn map8 is the first time the whole triangular plot of land is documented. The Trio Steam Laundry was still present in 1899 and had a new ironing addition. It is unsure if the Keeley Institute still remained at the same place in 1899, but in 1909 they moved to a new location at 229 Woodward Avenue.9 The 1898 City Directory reveals the residents of the triangular plot.10 The Directory does note that parcel 4 was vacant, so the Keeley Institute likely relocated to the new location between 1892 and 1899.

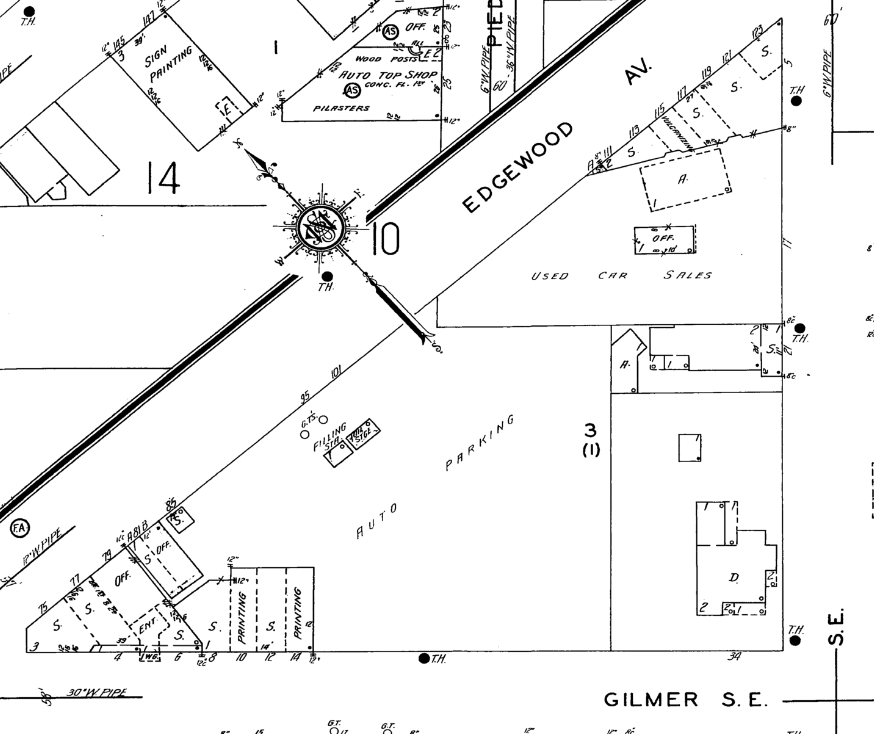

1911 and Forward

In 1911, there is still evidence of residences and businesses.11 The Atlanta Telephone & Telegraph Offices took over where the Keeley Institute and the Trio Steam Laundry used to be. A new laundry store was on the corner of Courland and Edgewood next to other stores (labeled ‘S’). 20 years later, the only dwelling that remained was parcel 34.12 In 1931, there were shops on the SW and NE corners of the triangular plot. Where the old dwellings used to be was then used for parking. The decline of this area from more residential to majority parking made it a good contender for the future park that would open in 1940.13

Joel Hurt

Joel Hurt was born in Hurtsboro, Alabama in 1850. Trained as a civil engineer, Hurt used to survey railroads in the West. By 1875, he resided in Atlanta and became interested in real estate. Noted for starting the Inman Park development and starting development of Druid Hills, Hurt also built major buildings like old Equitable Building which was the “city’s first steel-framed skyscraper.”To connect downtown Atlanta to Inman Park, Hurt’s East Atlanta Land Company built Edgewood Avenue to place a new streetcar line on. Hurt is the co-founder and first president of the “Trust Company” which was Suntrust Bank and is now Truist Bank. Joel Hurt is also known for the Hurt Building which began construction in 1913.14 Even though Joel Hurt shaped the skyline and history of Atlanta, the problem was how he sourced the materials for his buildings.

Joel Hurt was known for using the convict leasing system to create the materials for his buildings. This form of prison labor was a result of the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery. After businesses could no longer rely on enslaved people for labor, the legalization of the convict leasing system in 1868 essentially made slavery legal again. By ‘renting’ out prisoners for leases of 23 years maximum, businesses were once again able to have free labor. The treatment of prisoners in convict camps was so severe that many people died from injuries relating to whipping. In a camp leased by Joel Hurt, a prison fell ill and died after Hurt refused to provide medical care. Hurt also “demanded prisoners be whipped for singing and smiling.” He was the most difficult business owner to work with because he refused to follow the law. Additionally, there is evidence that Hurt “paid wardens a confidential second salary to ensure the mistreatment of prison laborers.”15

Joel Hurt’s troubling history with the convict leasing system can still be remembered in the city today with the Hurt Building and Hurt Park.

Hurt Park

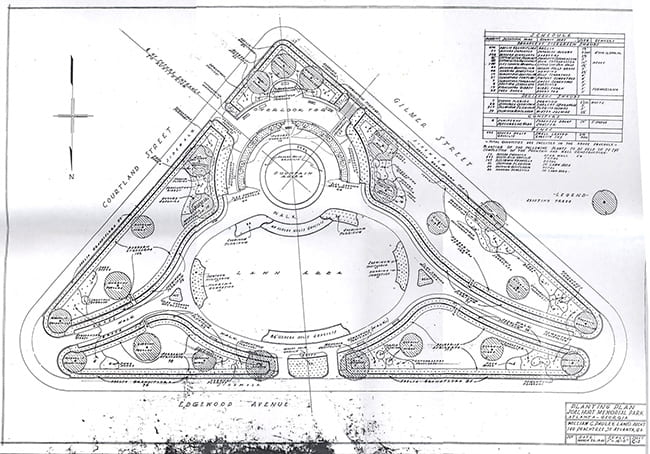

After Hurt Park opened in 1940, it was the first park to be built in the city since 1860. Designed by the architect William Pauley, the two-acre plot transformed the city during the New Deal era. In 1938, the city was remodeling the Municipal Auditorium, now GSU’s Dahlberg Hall, and plans for an “Auditorium Park” on the triangular plot across from the Municipal Auditorium were being addressed by Mayor Hartsfield. After much debate, the plan for the park was approved and funded by both the Work Progress Administration (WPA) and the Woodruff Foundation. On April 17, 1939, demolition of the buildings began. 16

The name changed from “City Auditorium Park” to “Joel Hurt Memorial Park” during a council meeting on December 18, 1939. Because it was renamed as a memorial park, it was later listed under parks that can never be sold. The park famously features an electrical fountain that has a light show. Pauley used the natural topography of the landscape to create a “bowl” for the fountain to sit in. Some of the notable landscaping features include the 7 Magnolia trees that were planted at each corner. These trees still stand tall today and are one of the greatest highlights to visiting the park, and the leaves remain green year-round.17

In 2022, renovation of the park began when the City of Atlanta and Georgia State University partnered together to return the park to its former glory. The fountain, granite stairs, walkways, and drainage all had to be updated.18 What was once a few parcels of residences and businesses was transformed into one of downtown Atlanta’s most important parks, but the history of these people and businesses should be remembered alongside the troubling history of the park’s namesake.

- Atlanta plans for opening of joel hurt park: Showplace will be complete in about two weeks. 1940. The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Nov 03, 1940. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/atlanta-plans-opening-joel-hurt-park/docview/503455705/se-2 (accessed April 22, 2024). ↩︎

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, 1886. Map 19. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_003/. ↩︎

- City Directories of The United States, New Haven, Conn: Research Publications. 1980. Internet Archives. Reel 2 1881-1886. https://archive.org/details/acpl_citydirectories_02_reel02/page/n657/mode/2up?q=gilmer ↩︎

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, 1892. Map 20. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_004/. ↩︎

- WAS A LADY’S MAN AND NOW IS MISSING: POLICE NOTIFIED OF THE SUDDEN DISAPPEARANCE OF C. E. T. NORTON. OWES TRIO LAUNDRY MONEY HE CUT QUITE A DASH AND HAD MANY YOUNG LADY ADMIRERS. BELIEVED HE WAS FOULLY DEALT WITH THE LAUNDRY COMPANY THINKS HE HAS SKIPPED OUT AND GONE NORTH. LEFT NEARLY TWO WEEKS AGO. 1898. The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Sep 14, 1898. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/was-ladys-man-now-is-missing/docview/495440537/se-2 (accessed April 23, 2024). ↩︎

- White, William. “Chapter 7.” Essay. In Franchising Addiction Treatment: The Keeley Institutes. Chestnut Health Systems, 1998. ↩︎

- INCORPORATED: THE KEELEY INSTITUTE NOW A PERMANENT INSTITUTION FOR ATLANTA–A PLACE WHERE SLAVES TO WHISKY AND OPIUM CAN BE RESTORED TO FREEDOM AND HEALTH. 1891. The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), May 03, 1891. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/incorporated/docview/193720563/se-2 (accessed April 22, 2024). ↩︎

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, FultonCounty, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, 1899. Map 6. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_005/. ↩︎

- A discussion of the world-famous keeley treatment for the cure of whisky, drug and tobacco habits, also neurasthenia or nerve exhaustion: The georgia keeley institute. 1909. The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Nov 07, 1909. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/discussion-world-famous-keeley-treatment-cure/docview/496256391/se-2 (accessed April 23, 2024). ↩︎

- Emory University. “Atlanta City Directory.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1898. https://archive.org/details/atlantacitydirec1898vvbu/page/170/mode/2up.

↩︎ - Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, FultonCounty, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, ; Vol.4, 1911. Map 451. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_009/. ↩︎

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, FultonCounty, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, ; Vol.1, 1931, Sheet 14. Map 14. https://digitalsanbornmaps-proquest-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/browse_maps/11/1377/6155/6523/97863?accountid=11226 ↩︎

- “Hurt Park (1939).” Hurt Park. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://tomitronics.com/old_buildings/hurt%20park/index.html. ↩︎

- “Hurt Park (1939).” Hurt Park. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://tomitronics.com/old_buildings/hurt%20park/index.html. ↩︎

- Rojas, Monique. “Joel Hurt: A 19th-Century Businessman Who Abused the Convict Leasing System.” The Signal, April 13, 2021. https://georgiastatesignal.com/joel-hurt-a-19th-century-businessman-who-abused-the-convict-leasing-system/. ↩︎

- “Hurt Park (1939).” Hurt Park. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://tomitronics.com/old_buildings/hurt%20park/index.html. ↩︎

- “Hurt Park (1939).” Hurt Park. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://tomitronics.com/old_buildings/hurt%20park/index.html. ↩︎

- Jones, Andrea. “Ribbon-Cutting Set to Showcase Hurt Park Renovations.” Georgia State News Hub, August 24, 2022. https://news.gsu.edu/2022/08/23/ribbon-cutting-set-to-showcase-hurt-park-renovations/.

↩︎