The American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association was chartered in 1922, in order to Americanize the immigrant Greek population. It was a long road to finally reach a general consensus that America was to be their home, but the consensus was reached and so began AHEPA.

The United States of America has been called a melting pot. Many people have come to America seeking their fortune and hopes of a better life; they brought with them their customs, religion, and language from the “old country.” These Immigrants to America were subject to bigotry and prejudice on arrival, because they talked different, worshipped different, and even danced differently. Assimilation in to the American culture takes time. When the Greeks started immigrating en masse to America in the late 19th century, they generally settled in groups that were from the same collective of villages and cities. They resisted a natural assimilation; because they did not view America as their home, but as a temporary settlement.Many of The Greek “colonies” in America existed in the northern industrial cities, but one “colony” settled in Atlanta. The Atlanta Greek community faced many challenges early on, as many Americans questioned their patriotism to America. [1]

To describe Atlanta in the late 19th century, it was not the most diverse city in regards to a Greek population. The Census in 1896 recorded 34 Greeks residing in the city. Out of whom, Alexander Carolee is recognized as the first. Carolee is known as the first Greek in Atlanta arriving in 1890 from Argos, Greece. In the beginning of the 20th century, the majority of Greeks in Atlanta were from the region the city of Argos and the rest of the Peloponnesus.[2] The reason for a large influx of Greeks into the United States was caused by the economic downturn in Greece. The depressed economy only led to the emigration of the population. Many Greeks grew up with the economic promises of The American Dream, and chose America as their new place of residence to make their fortune. To the average Greek, America wasn’t home, but rather a place of residence. Greece was the Fatherland (η Πατρίδα), and always would be their first country even if they were born in America. Like in many immigrant groups, staying close to those who belong to the same culture provides a safe haven. The same was evident for the Greeks; the establishment of Kinotis (κοινότης), community, created a frame work for the establishment of organization as a community. [3]

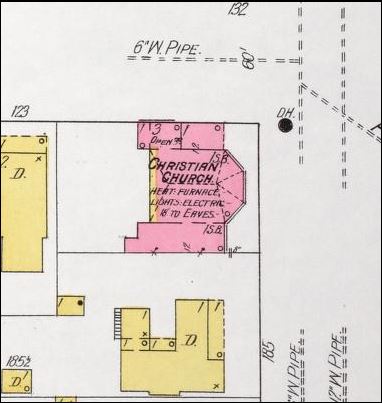

A few societies rose up to help bring the Atlanta community closer together. The need for a church was crucial to Greek identity; the Greek Orthodox Church is the organization that has no equal in a Greek community. The problem that the community faced was the lack of orthodox churches in Atlanta. In 1902 the Evangelismos Society was formed in order to find a place of worship for the community. Evangelismos (Ευαγγελισμός) is Greek for the Annunciation; the society’s name would also be the name for the church that they would charter. The Evangelismos society was charged by the community to find and raise money for a church. The society also acted as a fraternal organization educating the members in the laws and customs of the United States. The organization allowed only naturalized American citizens to vote in the society. The Greek Orthodox Church of Atlanta was chartered in 1905, and the Evangelismos Society bought a church to host as the first Orthodox Church in Atlanta in 1906.[4]

The Second Greek wedding to take place in Atlanta.

“Wedding of Atlanta Greeks; Second in history of city.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 10, 1907, The Morning Edition, D; c6.

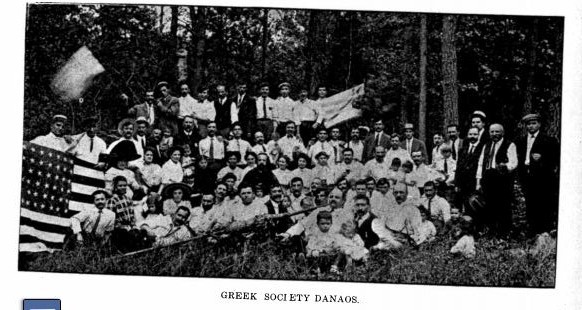

As soon as the community had a church, another society was founded in Atlanta to act as a mutual benefit and social outlet.[5] The Danaos society was formed in 1908 in Atlanta; the society’s name was symbolic of the Greeks living in Atlanta. Danaos was a mythological king who was father to the Danae, the firstinhabitants of Argos; such a symbol reflects the Greek population of Atlanta, since they were comprised mostly of immigrants from Argos. Localism plays a huge role in the life of the Greek; centuries of village life has molded the psyche of the Greek immigrant. It is a system that has existed since the days of Pericles; the Greeks organize themselves into their community not because they’re Greek, but because they’re from the same city in Greece.[6] Unlike the Evangelismos and Danaos societies, which were localized in Atlanta, there was another society that began to acquire over 150 chapters across the country.

The Pan-Hellenic Union, established in 1907 in New York, was the first national Greek American organization. The Union although “American” was strikingly Greek nationalistic, supporting Greece, and forgetting America. The Union tried to create a unified Greek American society, but failed miserably. The society proved itself as an agent of the Greek government, recruiting Greek-Americans during the Balkan wars.[7]

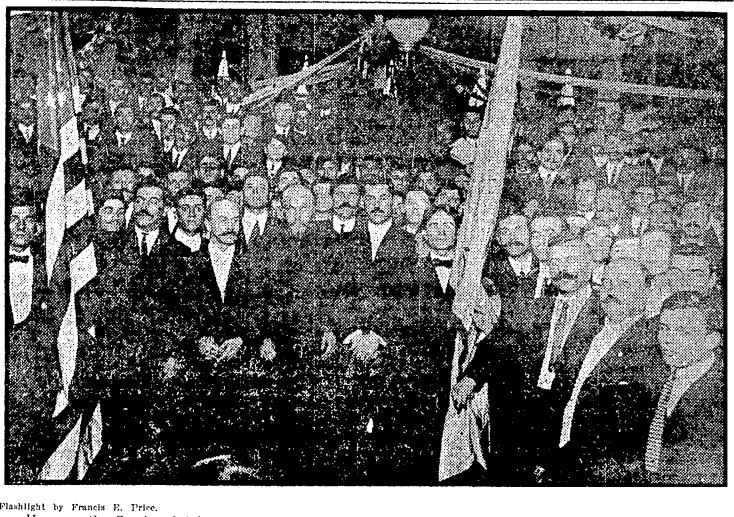

The Greeks of Atlanta preparing for war against the Turks.

“Atlanta Greeks pledge 100 volunteers and raise $12,000 for War on the Turk.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 7, 1912, The Morning Edition, ;3

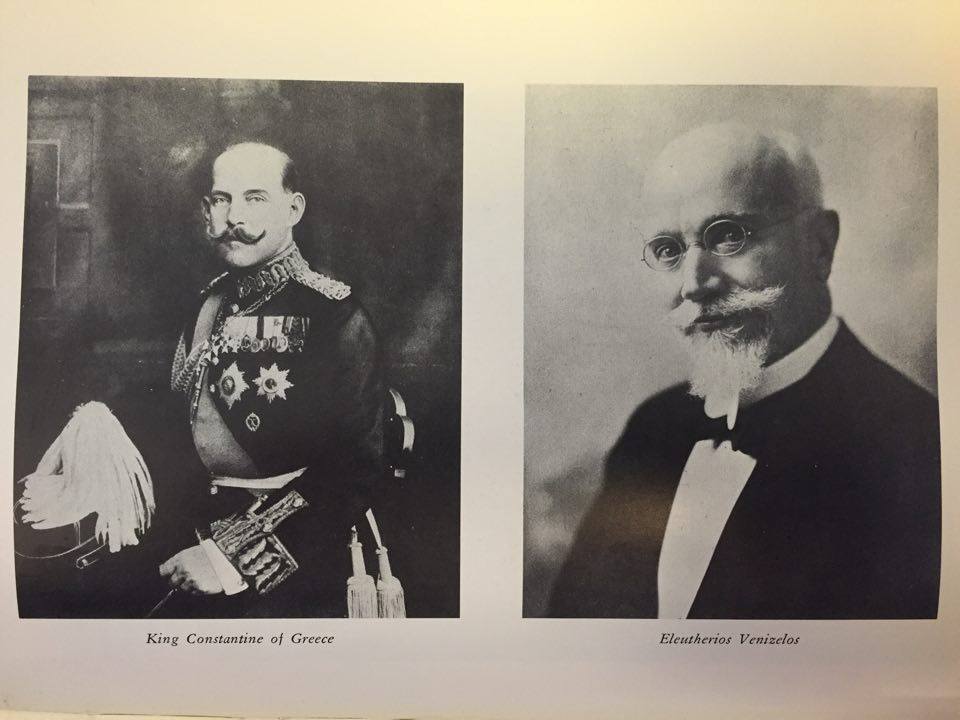

In 1912 war broke out between the Balkan countries and the Ottoman Empire; each state raced to grab as much Ottoman territory that they could occupy. In Atlanta alone, 100 men volunteered to fight for Greece; the Atlanta community raised $12,000 for the families of the volunteers.[8] The Greeks believed that this was the beginning of their ascendance back to Byzantine Greatness, a time where all the ethnic Greeks were part of one state. According to a 1907 census in Greece the total population was 2.6 million, however the total amount of ethnic Greeks living in the lands surrounding Greece totaled up to 6 million. The irredentist attitudes of Greek political life were unfathomable. Many plans were made about how Greece would incorporate the ethnically Greek lands into the Kingdom, but the means of doing that were up for question. On June 28th, 1914 Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand was shot on his visit to Sarajevo; his death sparked The Great War that would engulf Europe and the world. Through most of the War the Kingdom of Greece remained Neutral because the esteemed Prime minister Eleftherios Venizelos, an ardent supporter of the Entente, and King Constantine I, ethnic German and brother in law to Kaiser Wilhelm II. In 1916 Venizelos staged a provisional government in Thessaloniki that entered Greece into The Great War on the Entente side. In America most Greek-Americans lauded Venizelos as a hero, while other older Greeks supported King Constantine. Greek Americans kept following Greek political news, and yearned for a Greater Greece which was almost realized in the Greco-Turkish war of 1920.[9]

Left: King Constantine I

Right: Eleutherios Venizelos

Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in The United States (Harvard College, 1964).

The political aspirations in Greece were echoed in America; when King George I of Greece died, Greek Americans entered a state of mourning by wearing black arm bands. The politics of Greece brought the Greek-Americans closer together, and also ripped them apart. The American Greek came under criticism during the Royalist- Venizelist schism in Greece. Greeks were in open support for one faction or another and would physical or verbally repudiate the other faction, even clergy. The Pan-Hellenic Union died during The Great War due to corruption and American scrutiny due to its drastic loyalty to Greece rather than America. America at the time began a campaign of ultra-nationalism, depicting Imperial Germany as a monster race. Greek Americans were expected to show their loyalty to America by buying Liberty Bonds or joining the Army; joining the army in 1918 guaranteed full citizenship to aliens, such as the Greeks. As a whole Greek-Americans were on a path to become more American than they had ever been. The majority of Patrida (fatherland) organizations were fading in the tide of the war and were being replaced by more American organizations. Everything that had made them Greek: the Patrida, Orthodoxy, the Greek language were coming under attack in their place of residence in America.Due to the failures of politics in Greece, the Greek-Americans found that life in America was more promising. The population slowly realized, during The Great War, that their shops, homes, schools, churches located in America was their true home. [10]

The weekly advertisement of an AHEPA meeting that was located across the street from the Church.

“Display Ad 16 – No Title.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 12, 1929, The Morning Edition, 14.

In an effort to combat the mounting xenophobia in America, a few Greek-American societies were created . The most successful organization was the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Organization, AHEPA. Founded in 1922 the Atlanta based organization sought to protect its members from the activity of the Klu Klux Klan. Besides the horrid effects of xenophobia, AHEPA also sought to unite the Greek-Americans after the political schism that had left Greeks divided amongst each other. The charter of the organization states that the fraternal order would promote ”… pure and undefiled Americanism among the Greeks of the United States… [and] instill the deepest loyalty and allegiance of the Greeks of this country to the United States,” AHEPA sought to bring the Greeks into the American way of life, by establishing better relations with the non-Greeks. In 1924 AHEPA held 49 chapters across the United States prompting the organization to move its headquarters from Atlanta to Washington D.C. as a symbol that it was a national organization. AHEPA was the new chapter for the Greek-American; the society helped the Greek populations to become more attuned in American life and laws.[11]

AHEPA was the new direction that Greek immigrants took to become not just Greeks who live in America, but as full blooded Americans. The Greek culture wasn’t lost because of this new American move, but it was subsided marginally to where most Greek American’s first language is English rather than Greek. AHEPA went on to accomplish many things and is still in effect today. The road to the formation of AHEPA is an interestingly complicated yet simple tale of the American immigrant. Once the organization was set up Greeks began to become full-fledged Americans rather than those immigrants.

[1] Gary Gerstle, “Liberty, Coercion, and the Making of Americans,” Journal of American History 84, no. 2 (1997): 529.

[2] Stephen P. Georgeson, Atlanta Greeks: An Early History (Charleston: The History Press, 2015), 22.; Chris Savas, Centennial Anniversary of the Atlanta Annunciation Cathedral (Atlanta: Atlanta Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral, 2007),.

[3] Stephen P. Georgeson, Atlanta Greeks: An Early History (Charleston: The History Press, 2015), pages.

[4] “Greek Church buys building.” The Atlanta Constitution, July 12,1906, The Morning Edition, :6.

[5] Chris Savas, Centennial Anniversary of the Atlanta Annunciation Cathedral (Atlanta: Atlanta Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral, 2007), Pages.

[6] Yorgo Sklavounos, “A Model of Ethnic Development: The Greek American Community of Atlanta, Georgia” (Masters diss., Georgia State University, 1979), 51-55.

[7] Charles C. Moskos and Peter C. Moskos, Greek Americans: Struggle and Success (New Brunswick: Transaction Publisher, 2014), 52.

[8] Ann W. Ellis, “The Greek Community in Atlanta, 1900-1923,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 58, no. 2 (1974): 400.; “Atlanta Greeks pledge 100 volunteers and raise $12,000 for War on the Turk.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 7, 1912,;3

[9] Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in The United States (Harvard College, 1964), 138-159.; “Greater Greece.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 7, 1920, The Morning Edition, 10.; “Atlanta Greeks will wear black bands for dead king.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 20, 1913, The Morning Edition, 16.

[10] Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in The United States (Harvard College, 1964), 232-250..

[11] Saloutos, 246-248. ; Ahepa Charter of Incorporation, 1922, Fulton County Corporate Charter Ledgers, Archives of the Clerk of the Fulton County Superior Court