)

Downtown Atlanta is certainly devoid of many of its original prominent buildings. Just a few, such as the comically endearing wedge-shaped Flatiron Building and the lavishly decorated Candler Building sit amongst modernist monuments to an era of Urban Renewal and post-war corporatism. One of these surviving buildings was also the city’s first entry into the Art Deco wave of the late ’20s and ’30s, the William Oliver building.

Built in 1930, it was designed by Francis Palmer Smith of Pringle and Smith associates, and developed by the Healey Real Estate and Improvement Company. The building was named after William and Oliver, sons of the widowed Mrs. Ada who was president of the company. The lot chosen for the building is a corner on Peachtree Street at the Five Points intersection, or, the “so-called fourth busiest (inter)section of the nation”. It was built to seventeen stories, with 90,000 square feet of office space on 16 floors above bottom floor retail that held up to seven stores.1

Steel framing and concrete were used in the construction of the building,4 a new technique at the time, and similar to the way that the Empire State Building and newer skyscrapers are built now. Texan pink granite makes up the facade of the bottom three floors, and the rest of the fourteen floors are Indiana limestone with terra cotta accents. Other interior features consisted of brass elevators, floors made of marble and terrazzo, monochromatic chevrons, and foliate patterns typical of early Art Deco. Interestingly enough, however, the building fits in with many buildings of that time in Atlanta which were also fairly monochromatic compared to other buildings in other cities at the time.5

In 1931, just a year after opening, the William Oliver was already putting Atlanta into the national spotlight. The building’s storefront at the corner of Peachtree and Marietta Streets became the first and flagship location of Walgreen in the Southeast, which came along with a regional headquarters, distribution warehouse, and a manufacturing facility for ice cream. At the time, Walgreen was the second-largest drug store company in the world and was said to have been paying the highest rent of any drug store for retail space in New York City, a fact that surely made the Healey company and downtown Atlantan’s proud of the newest tenant.6

During a long process with several partners, including Central Atlanta Progress (CAP), it was decided in 1978 that the building and the surrounding blocks would be what was dubbed the Fairlie-Poplar project. This area surrounding two historic streets of Fairlie and Poplar contained some of the only surviving examples of Atlanta’s original downtown, and a district that was once referred to as Atlanta’s newest fireproof district. This new project took eighteen months to complete and cost the city over $400,000 to create. The revitalization initiative included redesigning Central City Park (now Woodruff Park) and Margrett Mitchell Square, Pedestrian malls on Poplar and Farlie streets, and road diets and streetscape improvements along Broad Street. Many of the private buildings including the William Oliver were refurbished fairly quickly and used about $64 million total of private money.7

After the expansive renovations to the building and the surrounding Fairlie-Poplar district, the downtown real estate industry was buzzing with excitement. Low vacancy rates for office space were finally catching up to a decade of new office buildings in and around downtown. The city was also looking forward to the eventual creation of new residential units downtown, something that had become very hard to come by after midcentury urban renewal efforts. Unfortunately for the William Oliver however the building was considered a bargain in the late ’80s. Even though the building was nearly 99% occupied, financial risk was still forcing the building to offer low rents of about $6 per square foot, nearly half of the rates in newer buildings at the time and even lower than that of rates in the much older Hurt and Candler Buildings. For $3 million, the William-Oliver and the nearby Flatiron building were sold to Jim Cumming, a 31-year-old from Toronto who was beginning to build up a portfolio of historic urban properties.8

In the mid-’90s, the William Oliver was still struggling to reap the rewards of the lofty investments of the early ’80s, and was fairly vacant. around $12 million in municipal bonds were awarded in 1995 to renovate the building again, but this time into 114 residential apartment units that the city hoped would start it’s long-awaited downtown residential boom this time aided by the looming activity of the 1996 Olympics. As the renovations were finishing up and the building was set to receive its first new tenants, unfortunately, irony struck and the bonds were declared in default by the lender who had recently become part of the Atlanta Development Authority. Thankfully, by the end of 1998, an agreement was struck and the bonds were taken out of default. The William-Oliver was reborn into a beautiful residential project and was already 98% leased.11,12

The William Oliver building today has remained a successful residential condo project. The outside facade still endows its handsomely muted granite and limestone facade, and its 90-year-old interior brass elevators and floorings are still in wonderful working condition. One of the buildings that Georgia State doesn’t own, it still provides service to the school, an affordable and convenient source of off-campus housing with easy access to the historic Fairlie-Poplar district in which the building calls home, and hopefully will continue to call its home for more decades to come.

First Image: Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center. (2011). William Oliver Building. Atlanta History Center. Retrieved from https://album.atlantahistorycenter.com/digital/collection/athpc/id/1187

- Shaefer, F. (1930, Sep 28). Six new skyscrapers to add 627,000 ft. to office space: Brings city’s rentable footage to 3,088,876; addition exceeds normal growth many times. The Atlanta Constitution, p. C5 ↩

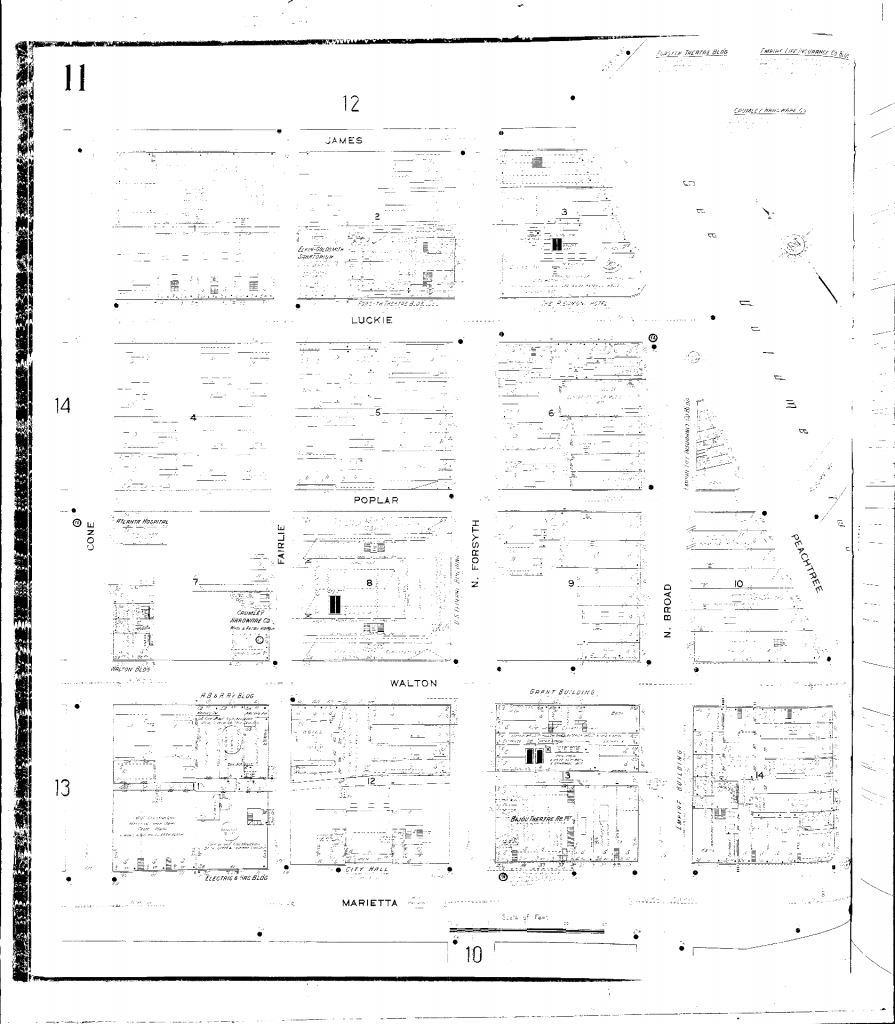

- (1911) Sandborn Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sandborn Map Company, Vol. 1, sheet 11. Retrieved from https://digitalsanbornmaps-proquest-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/browse_maps/11/1377/6154/6517/97193?accountid=11226 ↩

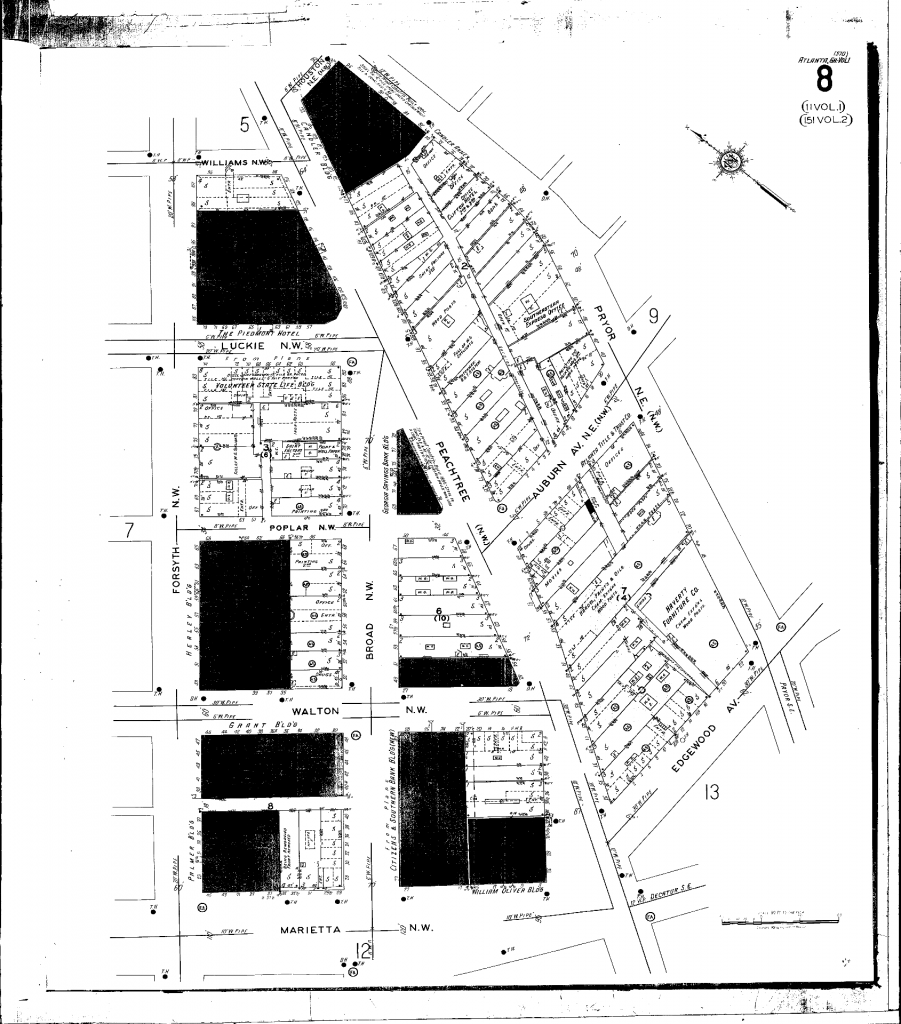

- (1931) Sandborn Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sandborn Map Company, Vol. 1, Sheet 8. Retrieved from https://digitalsanbornmaps-proquest-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/browse_maps/11/1377/6155/6523/97851?accountid=11226 ↩

- William-oliver building up seven stories. (1930, Apr 06). The Atlanta Constitution, p. 8C ↩

- Making Modern Architecture Palatable in Atlanta: POPular Modern Architecture From Deco to Portman to Deco Revival. 1988. Journal of American Culture (01911813) 11 (3): 19–33. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1988.1103_19.x. ↩

- BIG DRUG CONCERN COMES INTO CITY: WALGREEN COMPANY TAKES LONG LEASE ON WILLIAM-OLIVER BUILDING SPACE. (1931, Sep 13). The Atlanta Constitution, p. 1A ↩

- Robert Lamb Constitution, S. W. (1980, Mar 27). A fairlie-poplar idea: Something for everyone: Urban projects are notorious for falling by the wayside, but the plans for revitalizing downtown atlanta appear to be taking form, a cause for celebration at ‘the fairlie-poplar affair’ on saturday. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 1B ↩

- COLLEEN TEASLEY Journal-Constitution, B. W. (1978, Nov 19). Location can give old buildings an edge. The Atlanta Constitution, p. 7J ↩

- Architecture Tourist. (n.d.). Jewel box lobby – downtown Atlanta. Jewel Box Lobby – Downtown Atlanta | The Best Tourist. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://thebesttourist.blogspot.com/2012/11/jewel-box-lobby-downtown-atlanta.html ↩

- William Oliver Historic. (n.d.). The William Oliver Building. Retrieved from https://thewilliamoliver.org/about/. ↩

- McKenna, Jon. 1998. Atlanta Issuer Can Pay off Default with Funds from Equity Investor. Bond Buyer 326 (30514): 5. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=bth&AN=1270480&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↩

- McKenna, Jon. 1998. “Bonds Default in Atlanta Loft Project; Workout Expected.” Bond Buyer 325 (30456): 1. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=bth&AN=987469&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↩

- William Oliver Building from intersection of Peachtree and Marietta streets. (n.d.). Above Atlanta Realtors. Retrieved from https://www.aboveatlanta.com/atlanta-high-rise-condominiums/the-william-oliver-condos-atlanta.htm. ↩