Prohibition in Georgia has a long history; starting as early as the 1830s, temperance communities had become prevalent. Because of Atlanta’s explosive growth and development post-Civil War, saloons and other entertainment establishments were widespread throughout the city, particularly on Decatur Street. With an ever-increasing number of saloons, public drunkenness became commonplace, and the societal costs of drinking became more apparent. Saloons not only provided space for interracial mingling and intoxication, but they were also a symbol of the growing Black middle-class. These factors only incited tension among the races, further pushed to the brink by inflammatory publications that ultimately lead to a massacre of the Black community. The Riot of 1906 was the catalyst for Georgia’s statewide prohibition act, which sought to further disenfranchise minorities rather than address the societal issues at hand.

Control and Power

Prior to the inciting events, tensions were already at an all-time high; Black citizens within South were beginning to find their place among the White community post-Civil War. By the turn of the century, the Black community was becoming more prosperous with the city holding many Black-owned and operated businesses; however, this development spurred fear from Southern Whites 1.

White Southerners felt that growth in economic power for minorities would result in eventual political power as they would be able to accrue wealth. Also, during this time, evangelist prohibitionists began attempting to garner support from the Black community by framing the movement in such a way that the Black community could gain societal acceptance 2.

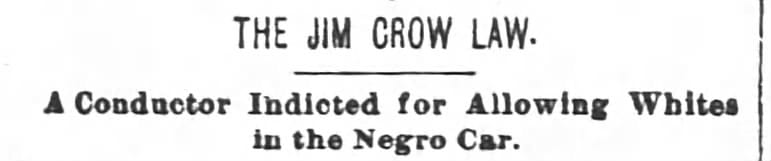

This time of prosperity did not last, however, and was largely broken down when Atlanta began implementing the segregationist Jim Crow legislature 4. The segregationist laws aided in leveraging the White prohibitionist agenda further through removing the personal freedoms of minorities. As anxieties continued to mount, the tension that led up to the riot was centered around the drunkenness of Black citizens and the threat they posed to society as a whole.

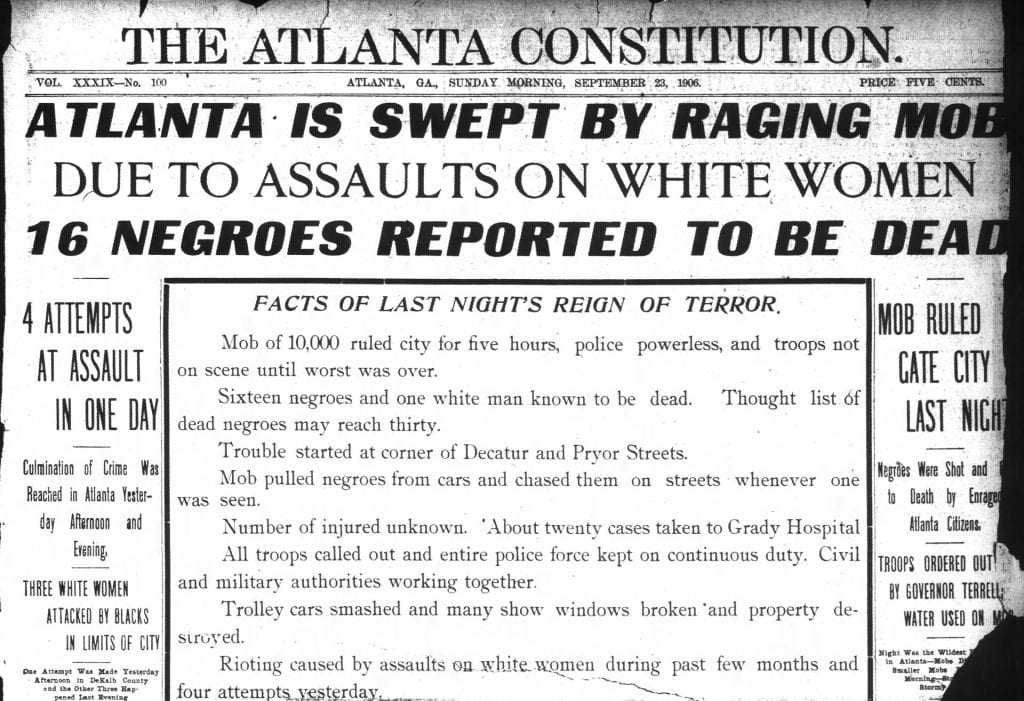

Race relations were further strained by Southern news publications creating inflammatory, often unsubstantiated articles about Black citizens assaulting people. These publications are ultimately what later incited the violence on September 22nd, 1906, that resulted in the prohibition of alcohol in 1907. As the temperance movement began to gain traction, Northern newspapers cited that this crusade was to suppress the Southern minorities due to White Southerners perceptions of Black citizens as morally bankrupt, especially when intoxicated 5. The movement also sought to employ some control over Black Americans in the South; it was believed that liquor provided an opportunity to deny their social standing, thus inciting them to attack White women. With the potential ban of liquor, it was believed that the alleged attacks would subside; however, these beliefs stemmed from false stories and prejudice, rather than true accounts 6.

The gubernatorial election between Hoke Smith and Clark Howell only accelerated the process as their platforms largely centered around white supremacy and the disenfranchisement of the Black community 7. One of the largest influences on the support for prohibition in Atlanta was when Hoke Smith created a linkage between the disenfranchisement of Black citizens and the ban on alcohol. By painting prohibition as a means to restrict the Black population, he was able to garner the support he needed to win the election for governor 8.

Photo: Former Governor Hoke Smith after his election of governor 9

The election of Smith only heightened the hostility among the races as White Southerners were aiming to disenfranchise minorities through any means possible, even violence.

While the Women’s Christian Temperance Union is largely credited with advertising the regulation and banning of alcohol, the Anti-Saloon League is largely what garnered the most support for the prohibition movement 10. This group, led by Wayne Wheeler, created what is known as pressure politics, which is to saturate the media with propaganda and intimidation tactics to support their campaign 11.

Photo: Article clipping from Atlanta Constitution about the Anti-Saloon League 12

In conjunction with prohibitionist sentiments, the Anti-Saloon League also incorporated anti-Black, anti-Semitic, and anti-immigrant rhetoric into their platform; this was all done in an effort to paint these minority communities as animalistic and morally corrupt 13. All of these factors worked together to create a contentious environment that was on the brink of disaster.

The Catalyst

The racist rhetoric spewed by both government officials and news publications created an incredibly strained environment for minorities. The final nail in the coffin came when The Atlanta Constitution published unsubstantiated articles about four sexual assaults on White women by Black men. Starting on September 22nd, 1906, White men gathered in downtown Atlanta with the intention of cleansing the streets of Black men. While it is cited that twenty-five Black citizens were brutally murdered, this number is disputed as the true total is unknown.

This vicious attack, however, did not result in the arrests of the perpetrators, but rather the victims, further highlighting that this attack was only propagate racist beliefs rather than to obtain justice. The riot also had effects on the economic prosperity of the Black community; many properties within the city were damaged during the riot, forcing Black citizens to relocate and flee the city altogether for fear of persecution.

Photo: News clipping from Atlanta Constitution from the day the prohibition bill was signed into law 15

Prohibitionists used this event to their advantage by hailing it as a “moral victory”; they claimed that preventing minorities from consuming liquor would protect them from committing crimes 16. After a short time, in 1907, the General Assembly passed a statewide prohibition of alcohol; Georgia became the first Southern state to go dry, although many states followed suit 17.

Aftereffects

When the statewide prohibition was enacted in 1907, it nearly destroyed Decatur Street 20. The loss of saloons was not merely a loss of space in terms of entertainment. Saloons provided not only communal space to immigrant and Black communities, but also operated as somewhat of a political institution; it was a place for minorities to learn about how to participate in American politics. The closure of these places essentially suppressed the poor peoples’ vote 21.

The closures were also a way to stunt the minority community’s growth by halting potential job opportunities within the sale or manufacturing of alcohol; the closure of such businesses eliminated thousands of jobs in service, manufacturing, shipping, and entertainment 22. It was also the source of an incredible loss of tax revenue; prior to the prohibition act, states relied heavily on the liquor tax. For New York, seventy-five percent of the tax revenue was from liquor taxes alone; at the national level, the United States lost nearly eleven billion dollars in revenue 23.

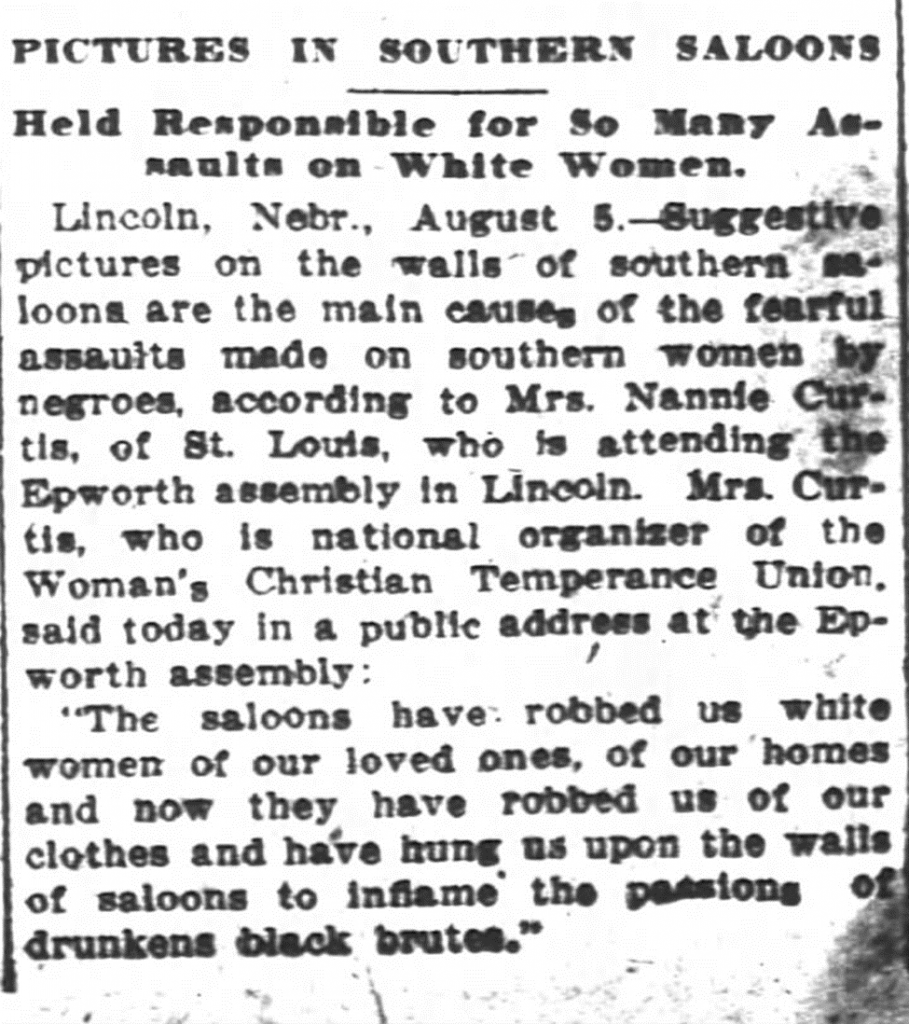

Saloons were also targeted as they provided space for interracial mingling, which at the time worried officials as it gave Black citizens the potential to ignore their social status. It was argued that these closures would improve race relations in the way of decreasing lynching as the result of inflammatory publications or unsubstantiated claims of drunk Black citizens assaulting the community 24.

Photo: News clipping from the Atlanta Constitution blaming saloons for the attacks on White women 25

So, these measures were implemented in order to exert the most control over minority communities as possible. The riot was painted in such a way that drunkenness had fueled Black citizens to commit crimes and had influenced White citizens to then retaliate 26.

The issue faced in the aftermath of creating this legislation was that while they were able to garner support, they were unable to maintain that support when it came to implementation and enforcement. Loopholes in legislation became apparent shortly after enactment; private locker clubs became widespread, in which alcohol was kept under lock and key and served to wealthy members only 27. This also spurred the development of “near-beer” saloons that used low-alcohol content beverages to evade the law 28.

These developments highlight the way that this initial movement was not to necessarily make Atlanta a “dry” city, but rather to put down minorities in the South. These laws only served to make sure that minorities were not able to accrue wealth and rise in social status in a racist community. While the prohibitionist movement is painted to be one of morality and good-naturedness, its history within Atlanta is anything but that. It sought only to disenfranchise minorities through creating an image of uncontrollable corruption when intoxicated. The movement used an unimaginable tragedy to leverage its stance, and unfortunately, their conniving tactics were successful. However, the Black community has continued to be resilient in the face of adversity.

First image: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “An illustration in Following the color line: An account of Negro citizenship in American democracy.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-1a46-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- Washnock, Kaylynn. “Prohibition in Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Jul 20, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/prohibition-in-georgia/ ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩

- “Jim Crow Law”, The Atlanta Constitution, January 2, 1893, https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=100493786&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI2ODE3NjI1LCJpYXQiOjE2NTEwMDAzMjYsImV4cCI6MTY1MTA4NjcyNn0.LTEGsiSd-vL4HUMqLTZF3njzfmvaqMBc3EhXEX02548 ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩

- Walton et al., “Blacks and the Southern Prohibition Movement.” Phylon (1960-) 32, no. 3 (1971): 247., p. 247, https://doi.org/10.2307/273926 ↩

- Walton et al., “Blacks and the Southern Prohibition Movement.”, p. 247 ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩

- Feldman, Glenn. Politics and Religion in the White South. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2005, p. 44 ↩

- The Atlanta Georgian., August 23, 1906. ↩

- Sismondo, Christine. “What Prohibition Teaches Us about Race Relations in the U.S.” Macleans.ca, June 16, 2020. https://www.macleans.ca/history/what-prohibition-teaches-us-about-race-relations/. ↩

- Sismondo, “What Prohibition Teaches Us about Race Relations in the U.S.” ↩

- “Anti-Saloon League Work“, The Atlanta Constitution, Feburary 5, 1905, https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=100492788&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI2ODY0MTYwLCJpYXQiOjE2NTEwMDM1MzQsImV4cCI6MTY1MTA4OTkzNH0.XPN7q5bF-Z8lmto0L8wI3ofEY_aJjMUAPUnNuEXPMNs. ↩

- Sismondo, “What Prohibition Teaches Us about Race Relations in the U.S.” ↩

- “Atlanta is swept by raging mob due to assaults on White women.”, The Atlanta Constitution, September 23, 1906, https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=100433565&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI2ODczMzk1LCJpYXQiOjE2NTEwMDM3NjUsImV4cCI6MTY1MTA5MDE2NX0.xwcllKs5wbs-fayjMNPr77EzDLz2FOdo__vyUjPKSAM ↩

- “Prohi Bill Signed Today”, The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1906, https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=100434537&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI2ODcyMTU0LCJpYXQiOjE2NTEwMDQ1OTIsImV4cCI6MTY1MTA5MDk5Mn0.dkEeqJQiwKa8AlOw26dDzPzXjrItSm_F1Hy9b8rn2pw ↩

- Crowe, Charles. “Racial Violence and Social Reform-Origins of the Atlanta Riot of 1906.” The Journal of Negro History 53, no. 3 (1968): 234–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2716218. ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, 1899. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_005/. ↩

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia. Sanborn Map Company, ; Vol.4, 1911. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01378_009/. ↩

- Feldman, Politics and Religion in the White South., p. 44 ↩

- Richard, Kristen. “Xenophobia, Racism and Classism: The Sinister Roots of America’s Prohibition.” Wine Enthusiast, March 8, 2021. ↩

- Lerner, Micheal. “Unintended Consequences.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/unintended-consequences/. ↩

- Lerner, “Unintended Consequences”. ↩

- Davis, Marni. Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2014., p. 120 ↩

- “Pictures in Southern Saloons.”, The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1907, https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=100434842&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI2ODcyMTU0LCJpYXQiOjE2NTEwMDU1NjcsImV4cCI6MTY1MTA5MTk2N30.05UpU2hg6_9fXSgSlBn8aVz5DPqqDPAjZlE8wDvRYcU. ↩

- Davis, Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition., p. 120 ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩

- Washnock, “Prohibition in Georgia.” ↩