One day, I grew curious after seeing the construction workers extending Grady’s complex building. I asked myself, “where Grady’s original building stands and how were the nurses and patients treated in the public institution?” Like any other institution, Grady started with one building. During the early and mid-20th century, the First Public Hospital in Georgia expanded. Grady mirrored the social structures in the south during Jim Crow segregation. Many people are not aware of the hidden story about the Training School of Nursing Program for Caucasian and Colored Nurses. In my report, I will discuss the origin and development of Grady Hospital, the Grady Hospital Nursing Training School, and the nursing training program’s history in the United States. I will also talk about the pioneers who pushed for equality. Unifying Grady Nursing Program created a promising future for the hospital.

Nursing and Hospital Care during the 19th century in the United States

Primary care took place at home throughout history. Nurses assisted family, friends, and neighbors with knowledge of healing practice. 1 Small religious hospitals flooded American cities throughout the 19th century. The hospitals reaped a profit gain from underprivileged patients because of inadequate access to health care. For this reason, underprivileged patients received poor care and unsanitized buildings. Also, patients suffered severe illness and death. 2 On the other hand, citizens who could afford health care received high-quality care. American Cities constructed and funded public hospitals for the impoverished community benefit.

The Origin of Grady Hospital

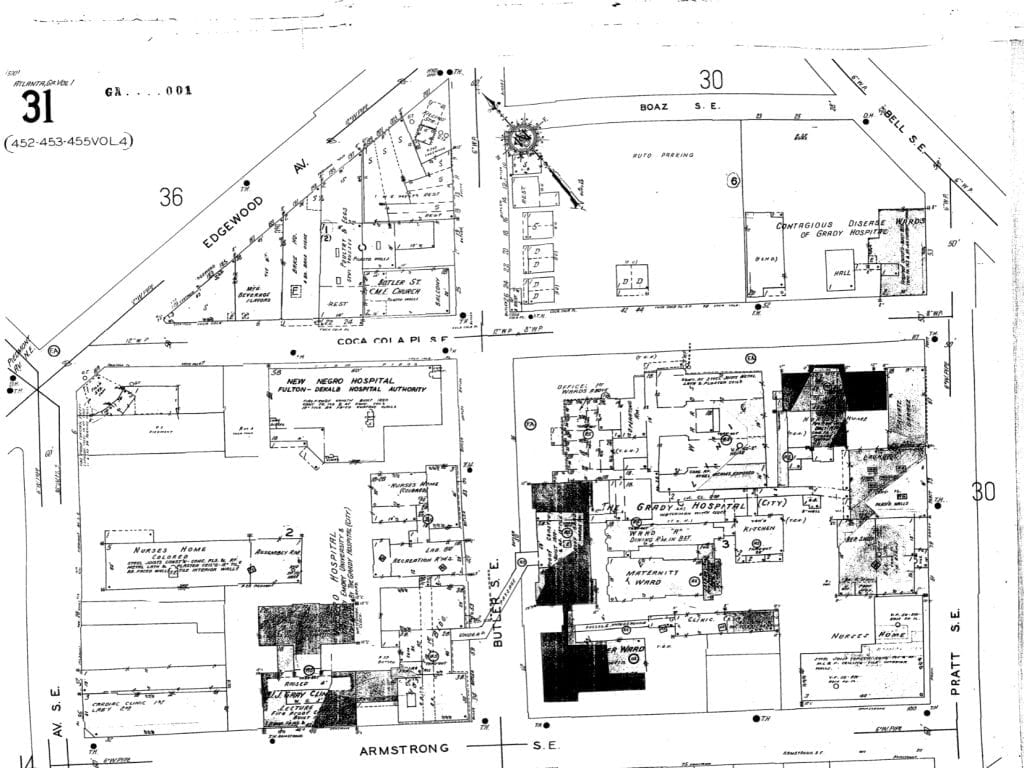

Mr. William Tuller developed the Atlanta Benevolent Home in the 1870s. The hospital stood before the old Grady Hospital in Downtown Atlanta. The public-funded facility provided care to Atlanta’s disadvantageous communities. The hospital suffered sanitation issues. For this reason, the Board of Committee dealt with a high volume of calls for removal in court. On the other hand, the Home’s Board of Committees dealt with lawsuits that prevented it from selling the deed. Along with his New South plan, Henry Grady, managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution, called for a public hospital in Atlanta to accommodate the needs and care to “treat citizens of all classes alike.” After Henry Grady’s death in December 1889, the board sold the building. Atlanta Councilmen Joseph Hirsch honored the building in Grady’s name.3 On June 2nd, 1892, the original Grady Hospital building opened its doors to black and white patients of all classes on Butler Street. Today, Butler Street is now Jesse Hill Jr Drive.4 Grady’s commissioners placed the building on Butler Street because it stood near the trolley lines. The trolley provided easy access for poor Atlantans to commute. The Board of Trustees also placed the building in that area because it stood near Atlanta Medical College. Today, the institution is Emory School of Medicine. The difference-maker, Florence Nightingale, ideas grew into Grady’s French pavilion plan. Florence Nightingale is a social and education reformer who pushed for proper treatment and sanitation in hospitals. Unlike religious facilities, the original Grady building instilled ventilation to reduce the mortality rate of patients. However, Grady’s Board of Trustees called for a new building during the 1900s because the building dealt with interior and sanitation issues. The building began with a small space and team. Divided by sex and race, the Romanesque-style building’s interior held “four doctors, 110 beds, a matron (the doctors’ wife), 12 male and female nurses, and 18 other employees, including cooks and engineers.”5 For this reason, Grady constructed a bigger hospital because the number of patients exceeded the beds, especially for African Americans. In 1898, Grady school of Nursing Program only opened to white students and staffs. Built through the Grady Aid Association, the Board added a children’s department in 1896.6 Surprisingly, having a limited number of horse-drawn ambulances in 1896, Black and White people were transported to the hospital together. During the last decade of the 19th century, the Romanesque building became known as Georgia Hall and lay in the presence of Coca Cola parking lot.7

The Development of Grady Memorial Hospital

Segregation between African Americans and Caucasians traveled with Grady Hospital until the mid-20th century. After World War One and Jim Crow laws grew intense in the south, Grady placed black and whites in their own facilities after 1921. Grady purchased the old Grady Hospital building, and constructed a new building south of the old Grady hospital, named Butler Hall for Caucasians. African Americans are at the old building at Atlanta Medical College. The separation of the buildings became known as the Gradys. The Fulton-Dekalb Hospital Authority took the initiative in funding Grady and controlled the institution in the mid-1940s. On March 18th, 1958, on Pratt Street, the new Grady hospital stood visible to the public. The expanded facility had a new 1,100-bed facility and 17 operating rooms. However, the idea of segregation didn’t fade. 9 The name of the “Gradys” lingered on the new buildings. I placed African Americans in the C and D areas, while Caucasians were placed in the A and B areas. Grady called out the Supreme Court to desegregate their facility in 1962. However, the facility didn’t integrate until 1965. 10

The History of the American Nursing Training Program

Florence Nightingale applied her nursing skills to the Crimean War in Turkey. She provided care for the allied and British soldiers in 1853. The dedicated leader spent numerous hours in the ward providing personal care for the troops, earning the name “the lady with the lamp.” 13 Nightingale’s caring act traveled to the civil war. Many enslaved women provided care to the wounded soldiers during the war. For these reasons, in 1873, nursing turned into a professional career in the U.S. Three nursing education programs began professional training in the United States. The nursing programs started at the Connecticut Training School at the State Hospital, the New York Training School at Bellevue Hospital, and the Boston Training School in Massachusetts. The three nursing education programs developed around the ideas of Florence Nightingale. 14 The success of the Nightengale Schools led to the program’s expansion in the United States. By 1900, somewhere between 400 and 800 schools went into operation in the U.S. and followed a typical pattern. (14. Ibid,1.) The School of Nursing Program provided clinical experiences to students, a necessity to practice as a nurse. Students received two to three years of training through the program. They had experience in the medical rooms with patients, taking college courses, and gaining exposure to campus life. After completion, nurses graduated from the program, practicing at the hospital facility they desired upon graduation.

The School of Nursing Programs at Grady Hospital During the Late 19th Through Mid 20th Century

In 1898, Grady’s three-year School of Nursing Program opened its doors to Caucasian Nurses.16. Mirroring the social changes in the south, the hospital only accepted Caucasian students and started in the new Butler Hall building by “Miss Annie Bess Feedback, the superintendent of the school of nursing program.” According to Emily Friedman, Caucasian students rested in the Feedback and Hirsch dorms. 17 They took classes at Georgia State College, now Georgia State University. Caucasians practiced clinically in the Butler building and children’s ward.18 Unlike Black nursing students, physicians taught White students.

Ludie Clay Andrews, a Spelman Nursing Graduate, Superintendent of Luda Grove Hospital Training School, and Georgia’s first black registered nurse, founded the Municipal Training School for Colored nurses in 1917. 20 Lula Grove Hospital shared connections with the Atlanta School of Medicine, merging later with Emory. Like the heroic and caring nurse, Nightingale, Andrews fought for morality and equality, striving to make sure blacks have a great education. For this reason, she refused registration, voicing her beliefs to the state board of Administration on why her sisters should have the same opportunity to take the state examination to obtain their license as whites on November 7th, 1920. 21 After she scored victory, the Fulton County Supreme Court licensed the program for Colored Nurses in 1917, graduating its first class in 1921. 22 When the heroic leader resigned from the program in 1922, Feedback, the director of the nursing program for whites, regulated the Municipal Training School for Colored Nurses.

After 1921, African Americans’ experience in the program aligned with the racial issues in the changing South. Grady Hospital renovated the Atlanta Medical College facility for Blacks while Whites remained in Butler Hall, referring to the separate hospitals as “the Gradys.”24In this building, many nursing students practice clinical trials with the help of Graduate Nurses. Black nurses dealt with a massive amount of patients. In fact, according to American Nursing, an Introduction to the past mentioned student nurses dealt with a lot of patients, but at Grady, this idea only applied to blacks. 25 The number of black, sick patients outweigh the bed spaces at Atlanta Medical College. Sadly, this issue lingered in the new building in 1958. A Caucasian nurse saw the amount of patients Blacks had to deal with in the C and D new Grady building, wondering “how the nurses got through the day.” 26 Sadly, Black Doctors couldn’t treat patients, another problem that transitioned to the new Grady building. 27

Academically, many nurses attended classes at Spelman University until 1964. Blacks rested in the Piedmont and Armstrong Hall dorms. Again, Black physicians couldn’t teach African American nurses and work alongside them in the wards. During the time, African American medical interns didn’t exist at Grady. In 1952, Blacks could only treat private African American patients at Hughes Spaulding, now Children Healthcare of Atlanta.29 The Hughes Spalding building near Grady operated under the Fulton-Dekalb Hospital Authority. White staff doctors from Emory educated African Americans. A graduate nurse recalls her experience, mentioning that some nurses didn’t make it through the program because they suffered illnesses, didn’t pass exams, or experienced disciplinary issues.30 Here, African Americans suffered harsh treatment in the program. In 1958, Georgia State and Spelman College agreed for nursing students to take introductory science courses at the collegiate level. The uniforms at Grady were different. Caucasian nurses wore white uniforms and caps, and African Americans wore black uniforms and caps. Also, in 1958, the Fulton-Dekalb Authority shifted the program’s name to the “Grady School of Nursing Program.” 31 For this cause, many would expect both races to wear the same uniforms since the name merged. However, nurses didn’t wear the same uniform until 1964, when John Bell, a Black dental surgeon, fought for equality and the desegregation of Grady.

Bell V.S. Fulton-Dekalb Hospital Authority, and the Integration of Grady Hospital (1962-5)

As aforementioned, Hughes Spalding Hospital’s staff doctors and surgeons experienced the same issues as the nurses at Grady Hospital in 1952. Sadly, there weren’t many graduate nurses on-site, and many ill patients had to wait hours for treatment. Dr. R. C Bell, a pioneer who witnessed the illnesses of the private patients and segregation at Grady Hospital, pushed for the desegregation of Grady Memorial Hospital. Grady hospital received public and federal funds from the government for construction. However, the funds implemented to repair the hospitals didn’t support African Americans. Unlike whites, Grady didn’t offer African Americans medical internships. Those who were physicians couldn’t work in the wards alongside their black sisters. The social reformer Bell took the issues to the Supreme Court in 1962, calling for integrating Grady Hospital. The court rejected the problems, sending the issues back to the FDA. 32 Fearing change, the Authority called for a meeting, but didn’t notify Bell. The industrious leader applied pressure on the committee, adding the civil rights leader, Dr. King and all college students in Atlanta to protest against the cruel injustices of African Americans. After three years of attacking the commissioners, the federal court passed the law, announcing the integration of the hospital, patient care, medical staff, and training in 1965.33

The Integration and Ending of the Grady School of Nursing Program (1965-1982)

After the school of nursing program integrated, they shared the same dorm rooms, took classes together at Georgia State College, had the same curriculum, wore the same uniform, caps, pins, and worked together in the wards. Caucasians didn’t know how to communicate with Black nurses and patients. Adapting to an unfamiliar environment and experience, one graduate student recalled the experience as weird. 34 Grady’s Authority placed Caucasian and African Americans in the dorms alphabetically by their last name. Some became close friends, while others switched their roommates. After the South integrated, the race relations grew slowly. As time passed, Grady experienced a low enrollment rate until 1982, the date when the authority graduated its last class and end the program. For this reason, nursing students attended four-year colleges to get a bachelor of science in nursing rather than seeking Grady’s three-year associate program.

The Legacy Pioneers and the Grady School of Nursing Left Behind for Grady Memorial Hospital Today

After Grady Memorial Hospital removed the School of Nursing Program in 1982, they allowed nursing students to train from Emory and Georgia State University. Because of Grady’s nursing program and infrastructure development, both races can work alongside each other, providing the best care and treatment to patients. The largest public hospital in Georgia is expanding its buildings today to support the community’s health. The pioneers who pushed for equality in the healthcare system and Grady created a promising future for Grady Hospital.

- Penn Nursing, “American Nursing: An Introduction to the Past.” Penn Nursing, University of Pennsylvania. https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/american-nursing-an-introduction-to-the-past/ (Accessed April 13, 2022) ↩

- Patricia D’Antonio, “History of Nursing.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/nursing (Accessed April 13, 2022) ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Grady’s Board of Trustees, Grady Hospital Annual Report, 1929 ↩

- Conner Lee, “The Grady Hospital.” ↩

- Grady’s Board of Commissioners, Grady’s Hospital Annual Report, 1899 ↩

- Lee, “The Grady Hospital.” ↩

- Conor Lee, “The Grady Hospital.” History Atlanta. http://historyatlanta.com/the-grady-hospital/ (Accessed April 12, 2022) ↩

- Emily Friedman, “U. S Hospitals and the Civil Rights act of 1964,” Hospitals and Health Networks Daily 2014, 2. ↩

- Grady Memorial Hospital, Grady Memorial Hospital Ninth Annual Report, Atlanta, Georgia: Fulton-Dekalb Hospital Authority. 1954, 20 ↩

- History.com Editors, “Florence Nightingale.” History. https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/florence-nightingale-1 (accessed April 12 2022) ↩

- History.com Editors, “Florence Nightingale.” History. https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/florence-nightingale-1 (accessed April 12 2022) ↩

- Louise Selander, “Florence Nightingale.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Florence-Nightingale (accessed April 13th, 2022) ↩

- Ibid. 2. ↩

- “Civil Rights Act of 1964.” ↩

- “The History of Grady Hospital and its people.” Undated, Vl, Box:44, Folder:43. Bernice Dixon Papers, L2016-06. Special Collections. ↩

- “U. S Hospitals and the Civil Rights act of 1964,” 5 ↩

- The Atlanta Constitution, “Grady Memorial Hospital.”Grady Hospitals desegregated, June, 2nd, 1965, 1 ↩

- Atlanta Constitution, “Final Rites Today for Ludie Andrews,”. The Atlanta Inquirer, January 1969, 5 ↩

- Conclave Constitution, Ludie Andrews Committee, Eighth Conclave 1975, 1977, 1987, Subseries A., Box 9, Folder 1. National Conclave of Grady Graduate Nurses Collection, aarlo5-oo1. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History. ↩

- Ibid, 1. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- U.S Hospitals and Civil Rights of 1964. ↩

- U.S Hospitals and Civil Rights of 1964. ↩

- American Nursing. ↩

- Friedman, U. S Hospitals and Civil Rights of 1964, 4. ↩

- Atlanta Constitution, “Grady Memorial Hospital.” The Grady News, December 23rd, 1890, 1 ↩

- Ibid, 6. ↩

- Grady(Hospital) 1961-1962, Box 1, Folder 2. Ray Moore Collection, aarl93-003. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. ↩

- Grady School of Nursing publications, 1978, 1989, 1992 undated, Subseries U., Box:12, Folder:22. National Conclave of Grady Graduate Nurses collection, aalo5-oo1. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History. ↩

- Ibid, 10. ↩

- George. M. Coleman, “Grady Accepts Negro Interne; ” Hospital Authority reduces Pavillion to a “Ward,” The Atlanta Constitution, February 3rd, 1962. ↩

- Sit-ins, 1959-1963, Box 1, Folder 20, Ray Moore collection, aarl93-of. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History. ↩

- Emily Friedman, “The U. S Civil Right Act of 1964,” 3. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Grady Nurse Programs, Series Vll, Box 32, Folder:9. National Conclave of Grady Graduate Nurses Collection, aarlo5-oo1. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History. ↩