Despite his relatively brief career, Bobby Jones is universally recognized of one of the greatest golfers of all time. His name, in the minds of the sporting world, does not sound out of place spoken among the names of far more contemporary players such as Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods or even those whose fame and feats are even more recent than they. The same can be said for few other athletes of his time- Jones retired from golf at the age of 28 in 1930. By that time, he had won 13 major championships. In the year of his retirement, he won all four, making him the only golfer in history to win the impregnable Grand Slam. The very next year, however, he would not compete in one tournament. Wrote the great sportswriter and best friend of Jones, “the greatest competitive athlete of history closed the book, the bright lexicon of championships, with every honor in the world to grace its final chapter.”[1] And yet, Jones never made one penny from playing golf. He was always keen to remind fans that “some things were more important than winning.”[2] This decision spawned from an intense modesty for which he is famed. On several occasions, Jones called penalties on himself in major championships- penalties that would not otherwise been assessed; one of these that cost him a victory.[3] And yet his scrupulous honesty, stringent self-governance and vivacious energy to achieve were not just limited to golf.

Double-decker buses in parade welcoming Bobby Jones to Atlanta, Five Points, Atlanta, Georgia, July 14, 1930. (AJCP338-037f), Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Jones was a lawyer by profession and his legal career was far more extensive in years than was his golf career. After his retirement, he joined his father’s firm, Jones, Evins and Moore in Atlanta’s Fairlie-Poplar District, where he would practice in its various incarnations until his death in 1971.[4] His legal education, however, began well before his retirement from golf in 1930. He entered Emory University’s Lamar School of Law in 1926, having already received a Bachelor of Science degree from Harvard and a mechanical engineering degree from Georgia Tech.[5] During the three semesters that it took for Jones to pass the bar, he led his class, and in the Spring of 1928, had the highest marks of any student in three of his five classes and received the first A in a contract law course in two years, while at the same time winning The US Open Championship, the US Amateur Championship and The Open Championship.[6] Legal practice, even as recently as the 1930’s, was not nearly as sectionalized as it is today and Jones’ specific legal profession was described as “General Practice.”[7] This included litigation as well as trial work, the latter of which Jones resented, once having said “I am not the sort of fellow who can do much standing on his feet and spouting a lot of words. I don’t believe that a sporting champion, as a rule, is much good at anything outside his game—but I’ve got a family to support.”[8]

Two stories added to Haas & Howell building; office space is in demand. (1922, Jun 11). The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945)

The history of the firms of which Jones was a part in his time as a lawyer is a convoluted one. Firms often merged and divorced, taking various sects of lawyers with them, dropping them altogether or adding new ones—even the handling of one sufficiently prestigious case might necessitate the rearrangement of a firm. This change would then be reflected in the name of the firm and in some cases in a change of location. By using city directories, one can trace the various incantations of Jones’ firms. As stated before, Jones joined his father’s practice of Jones, Evins, Powers and Jones in 1930. It was located on the 14th floor of the Citizens and Southern National Bank Building at 35 Broad Street. For a brief time, after dropping a partner and adding another, the firm was called Jones, Powers and Williams. It was located in the same office.[9] It would remain there, after becoming Jones, Williams and Dorsey, and then Jones, Williams, Dorsey and Kane until 1960. In that year, describes Frazer Durrett, a partner with Jones following this merger in 1960: “Bird & Howell [Durrett’s firm] advised its associates of a significant turn in our professional lives: Hugh Dorsey [of Jones’ firm] decided to accept the offer of Crenshaw, Hansell, Ware & Brandon… The remaining partners of Jones, Williams, Dorsey & Kane declined to move with Hugh, and instead proposed to merge with us, to become Jones, Bird, Williams and Howell.”[10] After this merger, Jones would practice on the fourth floor of the Haas-Howell building, located at 75 Poplar Street only three blocks northeast of the previous office. The last partnership of which Jones would be included was Jones, Bird and Howell. It was formed in 1961— ten years before his death. [11]

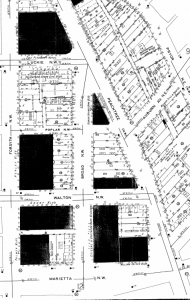

The following maps, which are adjoining, show the proximity of the buildings in which Jones worked.

Central Sector of Fairlie-Poplar District, Atlanta 1931-1932, sheet 7, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Southeastern Sector of Fairlie-Poplar District, Atlanta 1931-1932, sheet 8, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Jones was known known among the Atlanta legal community for his unwavering commitment to ethicality. In fact, Emory University hosted an annual lecture on legal ethics from 1975-2005 in his name. The inaugural lecture, which focused specifically on Jones’ character was given by Harry A. Blackmun, an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He said of Jones, there is a “complete absence, so far as I know or have read, of any besmirching or demeaning or unethical aspect in his legal or extra-legal career.”[12] According to popular legend, one of Jones’ first cases and one of his only trial cases was a wrongful death case involving an automobile struck by a train in 1936. Jones represented the railroad company, and upon hearing that Jones would be in his courtroom the judge presiding over the case invited Jones to play a round of golf, which Jones arranged from his Atlanta office the day before the trail commenced. Jones successfully defended the railroad company, but “his conscience began to gnaw at him,”[13] for he began to think that his fraternization with the judge might have perhaps been unethical. In the end, supposedly, “[h]e took out his personal checkbook and wrote the plaintiff a check for the full amount of the prayer for damages.”[14]

C & S Bank Building, Marietta Street and Broad Street (LBGPF1-049a), Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

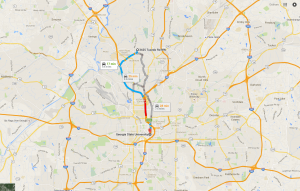

The cause of Jones’ death was a rare neurological disease called syringomyelia with which he was diagnosed in 1948. It progressed gradually, and as Frazer Durrett recalled, “initially he could walk with aluminum canes that fastened around his arms… Eventually he was in a wheel chair.”[15] Despite his status as an amateur golfer, Jones was quite wealthy not only from book sales, endorsements and his successful law practice, but from other ventures as well. Jones held stock in the Joroberts Corporation, a holding company for Coca-Cola Bottling in the South. Durrett recalls one amusing incident when he was in New York with Jones who was selling his stock in the corporation. One of his travelling companions was shocked to find he had been charged a dollar for a coke, to which Jones replied, “You know, Arthur, this is the only place in the world where they charge what they’re worth.”[16] He lived in Buckhead, at 3425 Tuxedo Road, even then a luxurious part of Atlanta.[17] The commute to downtown would have been considered lengthy, for there were no highways during the 1930’s into the 50’s, but this pattern was typical of wealthy Atlantans at the time—to work in the city and live in the surrounding suburbs. His affluence was also no doubt able to afford him more comfort and longevity given his condition. Bobby Jones historian Stephen A. Lowe describes his daily routine in the latter years of his disease thusly: “Each day around 11 AM his chauffeur would drive him in his tan Cadillac to his law office at the firm of Jones, Bird and Howell in downtown Atlanta. Once inside the building on Poplar Street, Jones would spend several hours answering mail or conducting an interview… Sometime between 4:00 and 4:30, Jones would be driven back to Whitehall. He sustained that routine until the last year of his life.”[18]

The following map shows possble routes that Jones might have taken to work in the Fairlie-Poplar district from his Buckhead home. The highlighted route would have only been possible following the completion of I-85 in the 1960’s.

Map of Bobby Jones Commute. 2016, Google Maps.

Jones’ time as a lawyer was not conventional by any means. He was enormously famous even long after his golf career had ended, and taking into account his ethical sensitivities, one might easily imagine that his celebrity might have given him some qualms about his practice. To quote an email from Sidney L. Matthew, a foremost Jones biographer, “Bob was a rainmaker and brought clients to the lawfirm but he did not ‘work’ on the cases and did no litigation. He helped to consult and negotiate contracts including his own.” This contracts refer primarily to those he negotiated with Coca-Cola. Jones’ was an Atlantan through and through and his involvement with the company seems only too appropriate.

Jones took on a somewhat heroic, but not a transcendent persona after his retirement from golf. Here was a man who has achieved arguably more than any other athlete in the world in his time, was globally recognized and yet, practiced law on a busy Atlanta street. His two lives, the first in golf and the second in law are almost formulaic for the construction of a civic icon: the sporting champion leaves home, returns victorious and reintegrates to the city of his birth, where he would die and is buried. There is scarcely a better testament to the type of man he was than the contents of his office in the Haas- Howell building. They were simple. There were many books (none were legal,) a layout of Augusta National, which he helped to design, a photograph of himself with his good friend Dwight Eisenhower and illuminated excerpt from a poem by his friend Grantland Rice that read: “For when the One Great Scorer comes To mark against your name, He writes – not that you won or lost – But how you played the Game.”[19]

[1] O.B. Keeler, The Bobby Jones Story (Atlanta: Tupper and Love, 1953), 301.

[2] Stephen R. Lowe, “Bobby Jones (1902-1971),” New Georgia Encyclopedia, accessed 15 April 2016.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Atlanta City Directory, 1931.

[5] Sandy Clower, “Bobby Jones Enters Emory University Law School,” The Atlanta Constitution, Septemeber 29, 1926, 8.

[6] BOBBY JONES LEADS CLASS AT EMORY IN LAW COURSE. (1927, Apr 08). The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945): 14.

[7] Atlanta City Directory, 1959.

[8] Robert T. Jones, quoted in Sidney L. Matthew, “The Trials of Bobby Jones,” Litigaton, Spring 2002: 53.

[9] Atlanta City Directory, 1958.

[10] Frazer Durrett, Jr., “Bob Jones,” article courtesy of Sidney L. Matthew, 1.

[11] Atlanta City Directory, 1962.

[12] Harry. A Blackmun, “Thoughts on Ethics,” Emory Law Journal, 3 1975: 1.

[13] Matthew, “The Trials of Bobby Jones,” 53.

[14] Ibid.

[15] James Frazer Durrett, Jr., interview by Erica Danylchak, Buckhead Heritage Society, January 12, 2012, transcript.

[16] Durrett, “Bob Jones,” 5.

[17] Atlanta City Directory, 1962.

[18] Stephen R. Lowe. “Demarbleizing Bobby Jones”. The Georgia Historical Quarterly 83 (4). Georgia Historical Society: 660–82.

[19] Durrett, “Bob Jones,” 2.

Works Cited

Atlanta City Directory. N.p.: n.p., 1931, 1958, 1962. Print.

Blackmun, Harry A. “Thoughts on Ethics.” Emory Law Journal 24 (1975): 3-20. HeinOnline. Web.

Clower, Sandy. “Bobby Jones Enters Emory University Law School.” The Atlanta Constitution, 29 Sept. 1926: 8. Web.

“Interview with James Frazer Durrett, Jr.” Interview by Erica Danylchak. Buckhead Heritage Society 12 Jan. 2012: n. pag. Print.

Durrett, Frazer. “Bob Jones.” Web. Unpublished article provided courtesy of Sidney Matthew

Keeler, O. B., and Grantland Rice. The Bobby Jones Story, from the Writings of O.B. Keeler. Atlanta: Tupper & Love, 1953. Print.

Lowe, Stephen R. “Bobby Jones (1902-1971).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.

Lowe, Stephen R. “Demarbleizing Bobby Jones.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 83.4 (1999): 660-82. Web.

Matthew, Sidney L. “The Trials of Bobby Jones.” Litigation 28.3 (2002): 53-74. HeinOnline. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.

“Bobby Jones Leads Class at Emory in Law Course.” The Atlanta Constitution [Atlanta] 8 Apr. 1927: n. pag. Web.