The history of Atlanta’s Carnegie Library is the story of a building, the story of the people who used its services and the story of the systems that were built to maintain and take advantage of it. Unknown to most Atlantans is that the public library system, seen as an everyday, normal part of life in Atlanta, had its very beginnings in that building. The story of this old building is particularly difficult to grasp because it has been torn down and replaced with the new Atlanta-Fulton Public Library on the same piece of land. In this report, I found it important to embrace the human element by discussing the works of individuals to create the Carnegie Library system, such as Anne Wallace and Andrew Carnegie. But I also did not wish to ignore the social and economic factors that affected it, such as the racial politics of the Jim Crow South. The connections between an international system of Carnegie libraries and the specific Atlanta branches helped to bring historical context and answer questions of continuity and perception.

Carnegie Way and Fairlie Street. “Carnegie Library,” LBGPF3-055p, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The roots of Atlanta’s first public library are, of course, very humble and small. During the aftermath of the Civil War and Atlanta’s subsequent rebuilding, a group of prominent Atlantans organized a private library system that used, depending on the years, rented office buildings or even the front rooms of some of its members. This Young Men’s Library Association usually allowed the public to come view its books in their reading room, but only members could take the books home. The first of these buildings was rented for the appallingly low amount of five dollars a month on Alabama Street. Soon, as Jamison states, “the library had become firmly established as an integral part of the social and cultural life of the city.”[1] This social nature resembles those of other civic organizations that were so prominent in the late 19th and early 20th century, such as the Chamber of Commerce is today. The YMLA’s civic organization nature puts it firmly in a category that generally excluded based on class, race and gender. Though they later allowed select women to become members, the YMLA still excluded many working class and minority Atlantans. These unfortunate people were not able to adequately educate themselves outside of a developing public school system.

The story of the Carnegie Library building itself, however, originates within the philanthropy of Andrew Carnegie, one of America’s wealthiest businessmen at the time. The initial donation of $100,000 was received in 1899 and was requested by Anne Wallace on behalf of the YMLA and public of Atlanta. As with all of Carnegie’s donations, the City of Atlanta promised to maintain and staff the library with at least $5,000 budget coming from public sources. The Atlanta Constitution article announcing the donation talked of YMLA interacting with the mayor and the city council to accept the donations and to help merge the organization with the Carnegie Library. The acceptance of the donation seemed to be uncontested and seen as the natural progression of the city’s public sphere, with the mayor predicting a unanimous vote within the city council. Remarkably, Atlanta was the first city in the Southeast to accept a Carnegie donation, following the example of many cities in the industrial Midwest, Washington D.C. and New York City.[2] Finally, the Carnegie Library opened its doors on March 4th, 1902.[3]

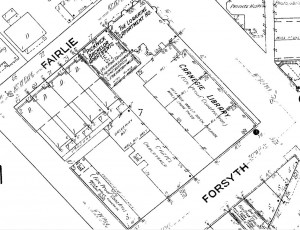

Carnegie Place between Forsyth St. and Fairlie St., “Atlanta 1911-1925”, sheet 12, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Anne Wallace seemed like a very interesting figure to me, because she was one of the most prominent figures of the early Carnegie Library as well as the first librarian. In this role, she went beyond the pale and did more than just manage the books. She wrote one of the first histories of the Atlanta library up to 1908. While reading this, I was struck by the amount of times she had to refer to herself, usually as “Anne Wallace, the librarian.” This wording, to me, reveals a certain pride in her profession and a premonition the unique history of the public library system as something worth remembering, long after her lifetime. She and some of her successors, like Alma Hill Jamison, are also notable because they were leaders and head figures of their public institutions, in a time when powerful and influential women were often scorned and never the norm. In addition to her writings, she took several additional steps to secure the future of the library, which was constantly receiving and purchasing new books, by receiving funds for branch expansion and additional buildings. One of the largest donations was again from Andrew Carnegie, who gave an additional $30,000 to build more branches of the library outside of Downtown Atlanta.[4]

Image from “Andrew Carnegie offers the City of Atlanta $100,000 with which to build a free library,” Atlanta Constitution, Feb. 8, 1899. 1

When discussing an early 20th century public institution in the South, issues of race and racial discrimination are impossible to ignore. When the Carnegie Library in Atlanta first opened, there were very few institutions available for black Atlantans to gain access to books. As Barbara Mamie Adkins quantifies in her master’s thesis to Atlanta University’s Library Science school, the only places that let blacks borrow books in Atlanta were the African-American universities in the city, such as Atlanta University. Continuing a tradition of separation and exclusion, when the Carnegie Library was built and opened, blacks were likewise denied access to its books and service. The efforts of W.E.B. DuBois and other black leaders to gain representation on the Library Board and be given “the same privileges that you propose giving to whites,” were initially resisted and ignored.[5] It took the head librarian of the Carnegie Library to personally contact Carnegie in 1916 asking if there were funds available for such a branch to be built. During this 17 year time frame, several other major Southern cities opened up segregated branches for blacks, including another city within Georgia itself, Savannah.[6] This resistance is representative of the cities common reluctance to maintain even the minimum Jim Crow standard of “separate but equal.”

The Atlanta Carnegie Library’s creation through the philanthropy of Andrew Carnegie is not unique. The capitalist’s donations created a system of public libraries that city and state governments supported through their own public funds. Throughout this system, there was a myriad of laws and boards set up to deal with these new institutions. However, these new measures were unable to keep up with the work of librarians and the desires of the public. The majority of these libraries were vastly underfunded and their collections were unable to expand beyond to the original building’s walls. Atlanta’s own public library system was in some ways exceptional, in that multiple branches were soon opened up to meet the needs of citizens throughout the Atlanta area. However, its annual budget was far smaller than the Carnegie Corporation or its employees recommended and needed. The Carnegie public library system, through its donation of “free” libraries, confirmed the public’s dedication to education throughout America to go along with the developing public library systems that were popping up around the same time.

While most of the historical tradition has praised the philanthropy of Carnegie’s donations to public libraries, others have criticized his efforts because of his connection to the labor struggle around the turn of the century. Siobhan Stevenson wrote of Carnegie’s connection with a rising capitalist and industrialist class that sought, through philanthropy, to gain favor amongst the public. Stevenson, and other radical scholars, argue that Carnegie’s public education endorsements have crowded out discussion of the labor movement’s role in the education and general well-being of the working class[7]. This view tends to focus on a discourse that has largely been ignored and forgotten because of a tendency towards monumental history that focuses on the individuals whose has been immortalized in brick-and-mortar.

The Carnegie Library in Atlanta operated for decades and was the foundation for a system that now serves Fulton County’s 920,000 residents with book lending, adult education and youth programs as part of a larger educational effort within the community.[8] Unfortunately, the Board of Trustees and City Hall alike decided in the 1970’s to replace the building. These two groups battled for their proposals to be enacted. The City of Atlanta preferred that the site of the Carnegie would be sold and another site on Peachtree Street would be bought and built upon to replace it. The Board of Trustees had the final say, however, and decided that the Carnegie Library would be demolished, due to worries that the sale of the site would not be enough to finance buying a new site.[9] Many of those worried about historical preservation protested against the demolition of the old library, such as William M. Griffin. In his article titled “Save Carnegie,” he advocated for the adaption of the property with newer buildings added on to supplement what was already there. He cites the efforts of cities such as Boston and Houston to preserve their old libraries as examples for Atlanta to follow.[10]

“Carnegie Library Demolition,” VIS 115.08.01, Martin Stupich Photographs. Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center.

And so the Carnegie Library became no more, and has been replaced by a building that is now being considered potentially replaceable. It is quite sad that the history within the walls of a building once heralded as the beginning of a new dedication to public service is seen as temporary and not worth preserving. It seems like the City of Atlanta has not considered itself amicable to the old, always aligning itself with the “Atlanta Spirit” idea that sees destruction as the key to a thriving city. Buildings that do not rely on much interaction with the public sphere, such as the Flatiron Building less than a block away, are more often than not renovated and considered historically significant. Perhaps Atlanta’s public library will always be this opportunistic cyclic beast that seeks to draw more business and people in through new buildings and shiny exteriors, while alienating and destroying the principles and hard work that made it special to begin with.

Photo taken by author

[1] Alma Hill Jamison “Development of the Library in Atlanta.”Atlanta Historical Bulletin, v. 4 (1939)

[2] “Andrew Carnegie offers the City of Atlanta $100,000 with which to build a free library,” Atlanta Constitution, Feb. 8, 1899. 1

[3] J.R. Nutting, “Carnegie’s Gift to Atlanta will become active today; attractive,” Atlanta Constitution, Mar. 4, 1902. 1

[4] “$30,000 Given Local Library for Branches,” Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 2, 1906: B1

[5] William F. Yust “What of the black and yellow races?” Bulletin of the American Library Association Vol. 7, no. 4, Papers and Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Library Association (1913): 164

[6] Barbara Mamie Adams, “A History of Public Library service to Negroes in Atlanta, Georgia” (master’s thesis, Atlanta University, 1951) : 7.

[7] Siobhan Stevenson, “The Political Economy of Andrew Carnegie’s Library Philanthropy, with a Reflection of its Relevance to the Philanthropic Work of Bill Gates,” Library & Information History 26, no. 4 (2010): 237-257.

[8] United States Census Bureau, General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010

[9] Jim Gray, “Trustees Say Demolish Carnegie Way Library,” The Atlanta Constitution, Jan. 30, 1976: 9A

[10] William M. Griffin “Save Carnegie” The Altanta Constitution, Mar. 2, 1977; 5A

[1] Alma Hill Jamison “Development of the Library in Atlanta.”Atlanta Historical Bulletin, v. 4 (1939)

[2] “Andrew Carnegie offers the City of Atlanta $100,000 with which to build a free library,” Atlanta Constitution, Feb. 8, 1899. 1

[3] J.R. Nutting, “Carnegie’s Gift to Atlanta will become active today; attractive,” Atlanta Constitution, Mar. 4, 1902. 1

[4] “$30,000 Given Local Library for Branches,” Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 2, 1906: B1

[5] William F. Yust “What of the black and yellow races?” Bulletin of the American Library Association Vol. 7, no. 4, Papers and Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Library Association (1913): 164

[6] Barbara Mamie Adams, “A History of Public Library service to Negroes in Atlanta, Georgia” (master’s thesis, Atlanta University, 1951) : 7.

[7] Siobhan Stevenson, “The Political Economy of Andrew Carnegie’s Library Philanthropy, with a Reflection of its Relevance to the Philanthropic Work of Bill Gates,” Library & Information History 26, no. 4 (2010): 237-257.

[8] United States Census Bureau, General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010

[9] Jim Gray, “Trustees Say Demolish Carnegie Way Library,” The Atlanta Constitution, Jan. 30, 1976: 9A

[10] William M. Griffin “Save Carnegie” The Altanta Constitution, Mar. 2, 1977; 5A