From the frontier of controversial art forms, a new generation of modern artists from around the world has been called to gather in Los Angeles. As a part of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s exhibition, “Art in the Streets”, street art often deemed as graffiti and vandalism now warrants payment for famous street artists. Among these artists, names like Blu, Bank$y and Shepard Fairey can be recognized because of their mainstream and even commercial success. Fairey’s world-renowned Barack Obama “HOPE” poster and the “Art in the Streets” exhibit signal the induction and acceptance of street art into a world of contemporary art. However, the anti-establishment and uncontrollable nature of street art predisposes artists to censorship, which only confirms the value of their artistic messages.

Blu

Blu, the pseudonym of an anonymous street artist from Italy, has achieved fame for his murals in Europe and South America. These paintings materialize slowly and painstakingly on the epic canvas of urban and industrial architecture, and Blu specifically considers the location of his murals. Besides using architectural structures in the formation of his paintings, the particular location of Blu’s murals decides their themes, often of protest and commentary on the state of society. Blu travels throughout the world painting murals such as “Global Warming” and “Gaza Strip”, which demonstrate environmental and anti-war concerns, respectively. Common themes of war, corporate greed and the environment characterize Blu’s purist street art as a controversial outcry against the current state of society.

Bank$y

Bank$y is an immediately recognizable name pertaining to street art. Known for his stenciling techniques, the English artist is vocal about his subversion of society. Qualifying graffiti and street art as a medium of artistic protest, Bank$y says, “if you don’t own a train company then you go and paint on one instead.”(3) Challenging the so-called powers that be, Bank$y and other street artists express their criticisms of society through their art, location, and subject matter. Artfully juxtaposing stenciled images in relation to their surroundings and calling attention to societal problems allows Bank$y to express his disillusionment with different facets of the world. Such as in the images above, he uses a child to portray his disillusionment with the political process and war, specifically juxtaposing a little girl patting down a soldier or painting over a stencil. As such, Bank$y demonstrates the absurdity of such concepts and their relevance to even the most innocent members of society.

3. Losowsky, Andrew. “Banksy Graffiti: A Book About The Thinking Street Artist (PHOTOS).” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 30 Aug. 2012. Web. 06 Dec. 2016.

Shepard Fairey

photo by John Colombo

Shepard Fairey is an example of a commercially successful street artist that qualifies graffiti as a viable art form. Known for his portrayal of Andre the Giant proceeded by the word “OBEY,” Fairey’s street art has become a commercially successful business and clothing line. Fairey contributes revenue from these commercial endeavors to non-profit organizations like Hope for Darfur, Feed America, earthquake relief in Haiti, and the Alaskan Wildlife Refuge. While Fairey continues to raise awareness of societal problems using street art, his commercial success has allowed relief of these same societal problems, demonstrating the tactfulness and usefulness of so-called vandalism.

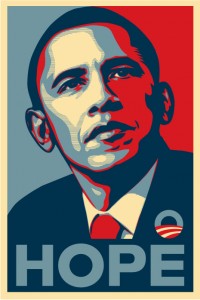

HOPE Poster

Shephard Fairey is the artist behind the iconic 2008 campaign poster for Barack Obama’s presidency. Much like many other of Fairey’s art pieces, this poster began as street art before becoming commercially successful and recognizable by pop culture, demonstrating an even further acceptance of street art in the mainstream.

The Gaza Strip

Blu’s street art provides ripe examples of the social commentary that graffiti often exhibits. Commissioned by a festival to paint “Gaza Strip,” Blu artfully juxtaposes bulldozers and tanks on a never-ending Möbius band to draw public attention to ongoing conflicts between Israelis and Palestinians.

Censorship Conclusion

An important distinction must be made between urban protest art and rebellious, anarchic, illegible tagging, as seen under interstate bridges. Street art occurs on a grand scale, and the themes and artistic forms are readily apparent. Such themes can be recognized in Blu’s mural through the analysis of his painting. Through the images depicted in his street art, Blu protests against a greedy corporate war machine, the rich that send the poor to foreign lands to fight for their financial interests. Relatively restrained compared to his previous anti-war murals, Blu’s censored depiction of coffins draped in dollar bills satirizes the well-recognized coffins of soldiers draped in American flags. This satire is meant to question the true motives of wars overseas. Yet the neat arrangement of the coffins and the coffins themselves are meant to respect the dead, honoring the sacrifice the soldiers have made. The mural simply questions the expense and value of life, in support of soldiers and war veterans against the arbitrary and unnecessary dispatch of soldiers and the ultimate loss of life. A private organization should value free speech, especially in their attempts to recognize this right in street art. The value and in fact the constitutional right to freedom of speech is meant specifically to protect unpopular and minority opinions. Now, as depicted in Blu’s mural, the favorable and popular opinions of wealthy men and corporations silence urban outcries for societal change and promote war. This protest, a protest against censorship, is the ideology behind street art. The censorship of street art, especially when commissioned by an organization with prior knowledge and therefore reasonable expectations, amounts to the censorship of the unpopular opinions and protest represented by the themes of street art.

The whitewashing of Blu’s anti-war mural characterizes censorship as the suppression of uncontrollable, unpopular opinions. No matter how unpopular the opinion, especially displayed in an appropriate way and commissioned by a museum, the value of free speech extends to art forms, especially those trenchant in protest and free speech themselves. Street art is a medium of uncontrollable protest and the outcries of unpopular opinions. The true motives of censorship often lie in a fear of the uncontrollable and an attempt to assert power over that which cannot be controlled. The value of unpopular opinions and public protest through all mediums of free speech could not be more important than they are in the wake of censorship. The Museum of Contemporary Art attempted to control an uncontrollable art, just as censorship attempts to control the uncontrollable outcry of people who believe it is time for society to change.

Commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art

Street art is characterized by its inability to be controlled. It fills lifeless architecture and blank industrial backdrops with an uncontrollable medium of protest, warranting censorship for the protest and change it could inspire. The Museum of Contemporary Art directly violated the principle purpose of street art in its attempts to cage an art form. Street art in museums is like “looking at wild animals in a zoo.”(1) Just as the true essence of wild animals is only displayed in the wild, their natural environments, street art belongs in the streets, and it certainly should not be surprising if it breaks containment. Art in the streets is a form of protest. It is controversial. It is uncontrollable. And it is not always pretty. Street art is regarded as graffiti and vandalism by masses of people disconnected from urban centers and urban youth because of its illicit display and controversial themes. Yet in an attempt to recognize the art form, the Museum of Contemporary Art failed to recognize the stylistic and demonstrative origins that define street art. The Museum of Contemporary Art’s whitewashing of an unfinished anti-war mural promotes the censorship of unpopular opinions, justified by their inability to be controlled.

Through the whitewashing of Blu’s unfinished mural, the Museum of Contemporary Art censored an artistic work meant to promote peace and inspire a desire for change in a society. With a full understanding of Blu’s schedule, local thematic strategy, and common themes, the Museum of Contemporary Art commissioned the world-famous artist to paint a mural on their Geffen Contemporary building. The museum and its directors gave approval to Blu to begin his painting upon his arrival, but a flight delay stalled the artist’s arrival, tightening the deadline for the mural’s display, intended before the full exhibit’s unveiling. The museum made little attempt to contact Blu, so, arriving late, the street artist began his work. Before it could even be finished, however, Blu’s mural was whitewashed by orders of museum director Jeffrey Deitch. The censorship of Blu’s mural received more controversial media attention than the mural itself. The mural was deemed too controversial and insensitive for its anti-war sentiment, but the censorship was often written off as another case of repairing the vandalism of graffiti or tagging.

1. Vaillancourt, Ryan. “MOCA Commissions Mural, Then Whitewashes It.” Los Angeles Downtown News. 14 Dec. 2010. Web. 11 Nov. 2016.

Censorship by the Museum of Contemporary Art

Unwavering from the principle purpose of street art, the mural’s inability to be controlled incited the censorship of Blu’s art, and the attempted justification serves to hide the museum’s lack of control. Despite prior knowledge of the wall’s location and the influence it would have on Blu’s ideas, museum director Deitch alone decided the mural was inappropriate for the area due to its proximity to a Veteran Affairs hospital and the Go For Broke monument honoring Japanese-American soldiers in World War II. Interestingly enough, the inscription on the monument apologizes for the internment of Japanese-American citizens as a response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Just as Blu’s censored mural contained anti-war themes, the war memorial maintains its own themes against the arbitrary actions of the American government during times of war. Even with a full understanding of Blu’s common themes against war and corporate greed, and especially his artistic process specifically involving coordination with the area, Deitch cited the Go For Broke monument as his main justification for the censorship of Blu’s controversial mural. Although the intention of the artist can be misconstrued, not a single person complained or asked for the removal of the mural, as the intention of the mural seems clear.(2) The depiction of controversial street art, especially as commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art and only exhibited temporarily, warrants no such censorship as justified by the museum director. Instead, the misinterpretation and presentation of unpopular opinions in street art justifies the censorship of an uncontrollable medium of public protest.

2. Vankin, Deborah. “Blu Says MOCA’s Removal of His Mural Amounts to Censorship.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 15 Dec. 2010. Web. 28 Nov. 2016.

Hourglass

Blu’s mural painting in Berlin, Germany depicts an hourglass with a melting iceberg and drowning city instead of sand in a particularly potent metaphor for global warming. The painting has since been removed in the year 2014, but its impact has persisted and been reproduced in many photos of the iconic street art.