Before the genre existed, Frederick Douglass wrote an autobiography entitled Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, often referred to as the Narrative. Douglass chronicled his intervallic existence from a man turned into a “slave” and, through hardship, into a man with agency. Born to an enslaved black mother and white enslaver father, Douglass grew up isolated as a “house negro.” Throughout the memoir, he examines the evolutionary process of overcoming the mental binds of enslavement through knowledge. Douglass learned to read from his enslaver’s wife, Sophia Alud, and white children in the neighborhood. Learning to read freed him more than physical freedom ever could, he states, “true knowledge unfits a man to be a slave.” With this knowledge, his contempt for enslavement and his enslavers heightened until he attempted to escape. After the first failed attempt, he finally escaped into physical freedom. In this Narrative, he condemns the false religious zealots, political hypocrisies, and the evil presence of enslavement within America. A critical aspect Douglass attempted to correct was his image. He attempts this through multiple mediums, including written and photographic forms.

Before the genre existed, Frederick Douglass wrote an autobiography entitled Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, often referred to as the Narrative. Douglass chronicled his intervallic existence from a man turned into a “slave” and, through hardship, into a man with agency. Born to an enslaved black mother and white enslaver father, Douglass grew up isolated as a “house negro.” Throughout the memoir, he examines the evolutionary process of overcoming the mental binds of enslavement through knowledge. Douglass learned to read from his enslaver’s wife, Sophia Alud, and white children in the neighborhood. Learning to read freed him more than physical freedom ever could, he states, “true knowledge unfits a man to be a slave.” With this knowledge, his contempt for enslavement and his enslavers heightened until he attempted to escape. After the first failed attempt, he finally escaped into physical freedom. In this Narrative, he condemns the false religious zealots, political hypocrisies, and the evil presence of enslavement within America. A critical aspect Douglass attempted to correct was his image. He attempts this through multiple mediums, including written and photographic forms.

The battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood. It recalled the departed self-confidence, and inspired me again with a determination to be free. The gratification afforded by the triumph was a full compensation for whatever else might follow, even death itself. He only can understand the deep satisfaction which I experienced, who has himself repelled by force the bloody arm of slavery. I felt as I never felt before. It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain as slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me. (137-138)

Frederick Douglass stole himself from the bondage of enslavement. After being placed with an exceptionally cruel “slave breaker” in Edward Covey, he unravels the emotional wound exposed from his time with Covey. He paints a complex portrait of a man freed from an oppressive force. There’s a sense of heroism in his words as he describes the climactic moment where the adversarial foe has been defeated, as he emerges victorious. This heroism is prevalent when he writes, “My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place,” and concludes with, “I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me.” The grimmest task of abolitionists was humanizing “the slave,” and he succeeds here by portraying himself as a positive force within the Narrative, where he presents himself as a free man first, and enslavement as a millstone or anchorage to iniquity.

Frederick Douglass stole himself from the bondage of enslavement. After being placed with an exceptionally cruel “slave breaker” in Edward Covey, he unravels the emotional wound exposed from his time with Covey. He paints a complex portrait of a man freed from an oppressive force. There’s a sense of heroism in his words as he describes the climactic moment where the adversarial foe has been defeated, as he emerges victorious. This heroism is prevalent when he writes, “My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place,” and concludes with, “I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me.” The grimmest task of abolitionists was humanizing “the slave,” and he succeeds here by portraying himself as a positive force within the Narrative, where he presents himself as a free man first, and enslavement as a millstone or anchorage to iniquity.

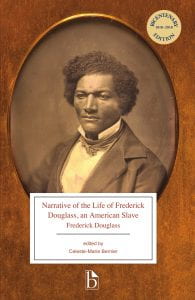

Photography garnered global popularity in the mid-to-late 1800s, and in the 19th century, Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American. People around the world were lured to these images, and more importantly, they were utilized as weapons to fight against the rhetoric of enslavement in America. Douglass successfully crafts himself in an image of freedom and fought against the “happy slave” trope. He purposely refused a smile to avoid with his grimaced fixed straight, forcing the audience to witness the true image of a “fugitive slave,” that has taken ownership of themselves. The image he promoted was fierce and unapologetic, which had a transatlantic audience.

Douglass’ most receptive audiences were located in Europe, where he shared correspondence with Scotland, Ireland, and the UK abolitionists. He reiterated his stances on enslavement everywhere he went, including his speech in Cork, Ireland. He again questions the “justifiable” system of enslavement when speaking to his audience.

The people of America deprive us of every privilege—they turn round and taunt us with our inferiority!—they stand upon our necks, they impudently taunt us, and ask the question, why we don’t stand up erect? they tie our feet, and ask us why we don’t run? that is the position of America in the present time, the laws forbid education, the mother must not teach her child the letters of the Lord’s prayer; and then while this unfortunate state of things exist they turn round and ask, why we are not moral and intelligent; and tell us, because we are not, that they have the right to enslave [us]. (Douglass)

He begins strong, identifying the southern rhetoric of enslavement such as inferiority and ignorance, but follows it with a retort. He begins challenging the usage of Christianity to justify enslavement and also the reasons behind the inferiority of Blacks, all circling back to education. He exposes the democratic system set that, “deprive…of every privilege” and then dare to speak of inferiority. After spending much of his time traveling in Europe, Douglass was more focused than ever on seeing his fellow “slaves” free, while also finding himself in freedom to just be a man.

Works Cited

Douglass, Frederick “FROM Cork Examiner.” 23 Oct. 1845, Cork, docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/support8.html.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Broadview Press, 2018, pp. 137-38.

Frederick Douglass. The Bridgeman Art Library, London. Frederick Douglass photogravure Brady Mathew Private Collection The Stapleton Collection The Bridgeman Art Library. n.d. , www.art.com/products/p9788798979-sa-i5576635/mathew-brady-frederick-douglass.htm?upi=PCHHXC0&PODConfigID=8880730&sOrigID=1841.

Miller, Samuel J. Frederick Douglass. 1852, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. www.whatitmeanstobeamerican.org/identities/why-abolitionist-frederick-douglass-loved-the-photograph/.

I was fascinated by the various images presented of Douglass within the Narrative. The “happy slave” depictions made me severely uncomfortable, but probably only because I had seen the original and correct ones. It’s interesting that the initial effect was the opposite of what the intention was for them. Douglass’ insistence on accurately capturing the spirit of a “fugitive slave” paves a way for the truth of slavery gripping its perpetrators.