Growing up thirty minutes outside of Atlanta has its perks. For me, the best thing about it was going to Braves games. By the age of 10, I considered myself a dedicated Atlanta Braves fan. I’d stay up late fantasizing about inviting Braves players to my birthday party or playing for the team in the big leagues. The main reason I live in Atlanta today is because those games made me fall in love with the city. Atlanta has so much life and energy so I’ve always been intrigued by its history. While Turner Field became the permanent home of the Braves following the 1996 Olympics, I never got the chance to witness a game in the Braves’ former ballpark, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Yet, the remnants of the coliseum still stand tall and firm, casting a long shadow over the infamous Turner Field ‘blue lot’ reserved for commuting fans. My passion for the Braves and curiosity of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium inspired me to identify the party responsible for bringing my favorite team to the city; that search led me to a familiar name, Ivan Allen, Jr. An individual whose impact on Atlanta stands tall and firm much like the memorial wall wrapping around the blue lot today.

Ivan Allen, Jr. (c. 1964), VIS 71.374.01, Floyd Jillson Photographs, reproduced with permission from Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center, Atlanta GA.

Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium Memorial Wall. Photograph taken by First Born, December 13, 2015.

Atlanta native, Allen Jr. ran a family owned office supply company and began his public service by serving as a treasurer of the state’s Housing Authority. Allen was a visionary, a man that wanted to bring a personal image of Atlanta as a national metropolis to fruition. According to the New York Times he “became president of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce” and in March 1961, as chamber president, “brokered an agreement between white merchants and black leaders for the desegregation of the city’s lunch counters at the same time schools were to be integrated.”[1] Allen’s public backing of integration led to notable support from the African-American community and gave him more influence over city affairs. Additionally, Allen outlined an extensive plan for the city while leading the chamber of commerce.[2] He advocated for completion of the expressway system, an urban renewal program, and a great stadium and coliseum. Allen initiated his plan by announcing his candidacy for mayor in 1962 and also pledged to bring a professional sports team to the city in order to place Atlanta on the national radar.[3] Because of Allen’s support of integration and his plans to improve the city, he was elected. Shortly thereafter, his plan developed during his tenure on the chamber of commerce commenced. Resulting from his push for an iconic stadium, Allen’s goal of urban renewal could be reached. By finishing construction on new expressways and building a coliseum, Allen assured the public a professional sports franchise.

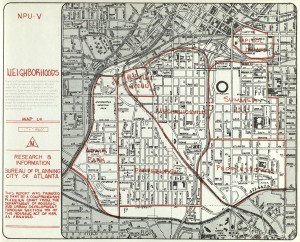

The Atlanta Constitution first reported Allen’s proposal of a potential site for the stadium. The newly elected Mayor identified Lakewood Park as a prime location due to its relative location to Five Points and several nearby expressways including some under construction.[4] The article claims that the city of Atlanta and Fulton County “will share costs of constructing a 40,000 to 60,000-seat sports stadium at Lakewood Park.”[5] However, despite Allen’s persistent efforts, he struggled finding a team willing to move to Atlanta. Initially, the Mayor had plans to bring the Kansas City Athletics to the heart of the South. Yet, Athletics executives feared the move would be vetoed by the American League conference of Major League baseball and abandoned the plan.[6] Eventually, Allen would reach out to the Milwaukee Braves. The Braves organization was looking for a fresh start in a new city and Allen convinced Milwaukee’s directors to seek approval for a move to Atlanta, Georgia. In 1964, the Atlanta Constitution reported that the Braves’ move was being finalized and quoted an extremely thrilled Allen who stated, “[the Braves] have chosen to make the ‘national pastime’ truly national, to give the 24 million people who live in these seven Southeastern states a share in the major leagues.”[7] Eventually, local leadership would select the Summerhill neighborhood as the prime destination for the stadium (pictured below).

“Atlanta, Georgia.” 1911-1925, Sheet 542, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Map of Atlanta Neighborhood Planning Unit V, 1976. Planning Atlanta City Maps Collection, Georgia State University Library. Courtesy of Georgia State University.

According to the Atlanta Daily World, Mayor Allen proclaimed that urban renewal involves “three big R’s- rehabilitation, redevelopment, and relocation.”[8] Allen asserted that each plays an integral role in renewing rundown areas. Yet, his vision of a stadium proved costly as the facts portray a very different side of Allen and the Braves; a ruthless business partnership aimed at doing whatever necessary to build a stadium. The Mayor contended that the Summerhill neighborhood was perfect as the stadium would sit near the Capitol and have easy access to several expressways. However, the project destroyed the community as the new interstates and ballpark replaced homes and displaced thousands of residents. Even though Allen’s original plan for urban renewal asserted that “there is no one thing that is more important to the welfare of the colored people of this community than additional living space,” his very actions proved differently.[9] Allen’s plans for urban renewal largely displaced low-income families and the local leadership never developed a plan for relocating these very residents. Essentially, Allen never sought public approval for the project or the construction of Atlanta Stadium. In “Limitations of the Past,” historian Daniel Judt claims that Allen was sure of the image of Atlanta he wanted and took public approval for granted.[10] While the innovative side of Allen depicted a new and improved version of the city during his campaign, Mayor Allen failed to uphold his promise of relocation to the colored community.

Atlanta Stadium (c. 1964), VIS 33.45.04, Marion Johnson Photographs, reproduced with

permission from Atlanta Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History

Center, Atlanta, GA.

Essentially, Mayor Allen’s decision was a bad judgment call as the construction created a barrier between downtown Atlanta and the city’s ‘southern slum neighborhoods.’ According to Judt, “had Allen and the Braves looked a bit closer at their barren tract of revitalized land, they might have found a very different story. They might have heard voices, drowned out by Atlanta’s relentless push for business and economic progress, voices of people who felt differently about putting a stadium in their neighborhood.”[11] Allen’s concerted efforts to use the stadium as a catalyst for the local economy fell short as the construction cost and abysmal attendance record led to economic turmoil stretching into the next decade. The Atlanta Constitution reports, “sell Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium? Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson says he is not advocating it… But, he says, it is one of the possibilities as the city continues to wrestle with its growing financial problems.”[12] Allen’s successor, Mayor Jackson, had to consider the possibility of selling the ballpark to alleviate tax burdens on the city caused by the construction of Atlanta Stadium and major expressways. Mayor Allen’s once credulous plan was being uncovered for what it truly was, a massive mistake. The image of Atlanta Stadium as being iconic faltered.

However, during his tenure Allen continued to champion the Civil Rights movement. The Mayor appeared before the Senate Commerce Committee to “testify on the public accommodations section of President John F. Kennedy’s civil rights bill” and “told the committee that the task would have been easier if there had been a national law” for desegregation instead of leaving it up to state governments. [13] In addition, the Mayor defiantly protested the election of segregationist Lester Maddox as Governor of Georgia. The New York times reported Allen as declaring “the seal of the great state of Georgia lies tarnished” and that “it is high time all Georgians put aside their prejudices and begin to realize that a large segment of our population that is Negro is entitled to full rights and privileges as American citizens.”[14] In 1966, following Allen’s utmost support for civil rights legislation, tensions between whites and colored residents began to rise. African-American communities began clashing with the Atlanta police force and anti-segregation groups. Allen’s response was notoriously bizarre as he traveled to the neighborhoods to ease the tension. On one occasion Allen “personally broke up street groups” and “climbed to the roof of an automobile and tried to speak through a megaphone” to console the crowd.[15] Allen’s persistence combined with law enforcement and ‘negro’ leadership eventually put an end to the conflicts. Because of his open advocacy for equality, Ivan Allen, Jr. developed a relationship with civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Following Dr. King’s assassination in 1968, Mayor Allen established a panel to plan a memorial for King.[16] By organizing a memorial, Ivan Allen, Jr. demonstrated his extreme gratitude and admiration for King’s fight for equality. In a New York Times article discussing Ivan Allen Jr.’s death in 2003, journalist Douglas Martin quotes Gary M. Pomerantz, author of “Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn,” as stating “over the turbulent waters of the 1960’s, Ivan Allen was the human bridge from the old South to the new in Atlanta… literally on his own back, he carried the city’s white establishment to a more enlightened day.”[17] Pomerantz’s statements illustrated Allen’s support of the civil rights movement and painted a more vivid image of what Allen’s dream for Atlanta truly consisted of.

In conclusion, despite Allen’s shortcomings with the stadium, his intentions were clear. The Mayor aspired to change the culture of Atlanta in order to make it a world-class city. The stadium was just a façade and the Braves were Allen’s way of unifying a segregated city. In his two terms of office the city of Atlanta experienced a dramatic increase in population and a dynamic shift in the attitude of its residents towards a ‘new’ South. A city eventually deemed ‘too busy to hate’ began to integrate and progress forward.[18] Ivan Allen, Jr.’s legacy is a major reason why Atlanta is so full of life and still the heart of the Southeastern United States. He’s the reason my favorite baseball team, the Atlanta Braves, call this city home. I chose to live here because I fell in love watching baseball at Turner Field. Without Ivan Allen, Jr., I wouldn’t have had the opportunity. Ivan Allen, Jr. helped make Atlanta what it is today: a world-class city.

[1] Douglas Martin. “Ivan Allen Jr., 92, Dies; Led Atlanta as Beacon of Change.” New York Times

(1923-Current file), Jul 03, 2003, 21.

[2] “Ivan Allen Outlines ‘Big Program’ At Southside Civic League Rally.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), July 13,

1961, 1.

[3] Kenneth Fenster. New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium,” August 11

- Web. April 5, 2016.

[4] “Allen Tells Plan for Stadium.” Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Mar 07, 1962, 10.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Max Rieper. SB Nation: Royals Review, “Losing a sports team: The relocation of the Kansas City Athletics,”

January 20, 2016. Web. April 10, 2016.

[7] Marion Gaines. “Mayor Allen Overjoyed by the News.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Oct 22, 1964, 1.

[8] “Urban Renewal is Praised by Mayor Ivan Allen Jr.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003),

Apr 03, 1964, 5.

[9] “Ivan Allen Outlines ‘Big Program’ At Southside Civic League Rally.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), July 13, 1961, 1.

[10] Daniel Judt, “Limitations of the Past: Atlanta’s Stadium and Atlanta’s Image, 1960-2015.” Yale Historical Review (Spring 2015): 91.

[11] Ibid.

[12]Joe Ledlie. “Jackson: Serious Economic Questions.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Dec 10, 1978, 1.

[13] E.W. Kenworthy. “Allen Still Sees Segregation as Biggest Issue.” The Atlanta

Constitution (1946-1984), Jul 28, 1968, 1.

[14] Reese Cleghorn.”Allen of Atlanta Collides with Black Power and White Racism.” New York Times (1923-

Current File), Oct 16, 1966, 251.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Alex Coffin. “Allen to Establish Panel to Plan Memorial for King.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Apr

16, 1968, 6.

[17] Douglas Martin. “Ivan Allen Jr., 92, Dies; Led Atlanta as Beacon of Change.” New York Times

(1923-Current file), Jul 03, 2003, 21.

[18] Reese Cleghorn.”Allen of Atlanta Collides with Black Power and White Racism.” New York Times (1923-

Current File), Oct 16, 1966, 251.

Bibliography

Alex Coffin. “Allen to Establish Panel to Plan Memorial for King.” The Atlanta Constitution

(1946-1984), Apr 16, 1968, 6.

“Allen Tells Plan for Stadium.” Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Mar 07, 1962, 10.

Atlanta Stadium (c. 1964), VIS 33.45.04, Marion Johnson Photographs, reproduced with

permission from Atlanta Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History

Center, Atlanta, GA.

Daniel Judt. “Limitations of the Past: Atlanta’s Stadium and Atlanta’s Image, 1960-2015.” Yale Historical Review (Spring 2015): 81-100.

Douglas Martin. “Ivan Allen Jr., 92, Dies; Led Atlanta as Beacon of Change.” New York Times (1923-Current file), Jul 03, 2003, 21.

E.W. Kenworthy. “Allen Still Sees Segregation as Biggest Issue.” The Atlanta

Constitution (1946-1984), Jul 28, 1968, 1.

Ivan Allen, Jr. (c. 1964), VIS 71.374.01, Floyd Jillson Photographs, reproduced with permission

from Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History

Center, Atlanta GA.

Joe Ledlie. “Jackson: Serious Economic Questions.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Dec

10, 1978, 1.

Kenneth Fenster. New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium,” August 11,

- Web. April 5, 2016.

Marion Gaines. “Mayor Allen Overjoyed by the News.” The Atlanta Constitution, (1946-1984), Oct 22, 1964, 1.

“Major Baseball Team Ready to Sign Contract To Move Here in 1965: Sole Hurdle Is Letting Of Stadium.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Mar 05, 1964, 10.

Max Rieper. SB Nation: Royals Review, “Losing a sports team: The relocation of the Kansas City Athletics,” January 20, 2016. Web. April 10, 2016.

Miracle Bisher. Fulton County Recreation Authority, “Assault on the Impossible,” Atlanta Stadium: Special Dedication Edition (1966): 15-16.

Reese Cleghorn.”Allen of Atlanta Collides with Black Power and White Racism.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 16, 1966, 251.

“Urban Renewal is Praised by Mayor Ivan Allen Jr.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), April 03, 1964, 5.