Summary

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 (1996), was a landmark U. S. Supreme Court case which ruled that prior to police interrogation, apprehended criminal suspects must be briefed of their constitutional rights addressed in the sixth amendment, right to an attorney and fifth amendment, rights of self incrimination. Ernesto Miranda appealed his rape and child kidnapping charges to the U. S. Supreme Court. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled police officers, detectives and/or other law enforcement officers must inform criminal suspects of their right to an attorney as well as their rights against self incrimination in order for evidence to be admissible in court. It was established that the defendant must know, understand, and explicitly waive these constitutional rights in order for them to be used at trial. Due to this ruling police officers, as shown in popular media, must read the detained suspect his or her Miranda Rights.

First Timeline

Background

In the 1930s, the “third degree” – using physical threats on suspects to get confessions – was a widespread police practice, raising concerns over police interrogation techniques. The Supreme Court reacted in 1936, with the Brown v. Mississippi decision which stated that confessions obtained via physical torture were inadmissible in court, because they violated the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause. However, police brutality persisted in the South.

Going forward in the 1940s, and mostly in the 1960s, pressure started to be used against defendants not in the form of physical coercion, but in the form of psychological threats. In response to these practices, the Supreme Court decided to add protections to suspects held in custody. In 1963, the Gideon v. Wainwright decision extended the Sixth Amendment’s right to have an attorney in criminal cases to state felony cases; and in 1964, in Escobedo v. Illinois, the Supreme Court held that the police needed to notify suspects of their right to remain silent and their right to counsel. Therefore, before the Miranda v. Arizona case was brought to the Supreme Court, the Court was sending a clear signal to law enforcement: constitutional guarantees of due process for suspects had to be maintained, otherwise confessions would not be admitted in court and convictions would be overturned.

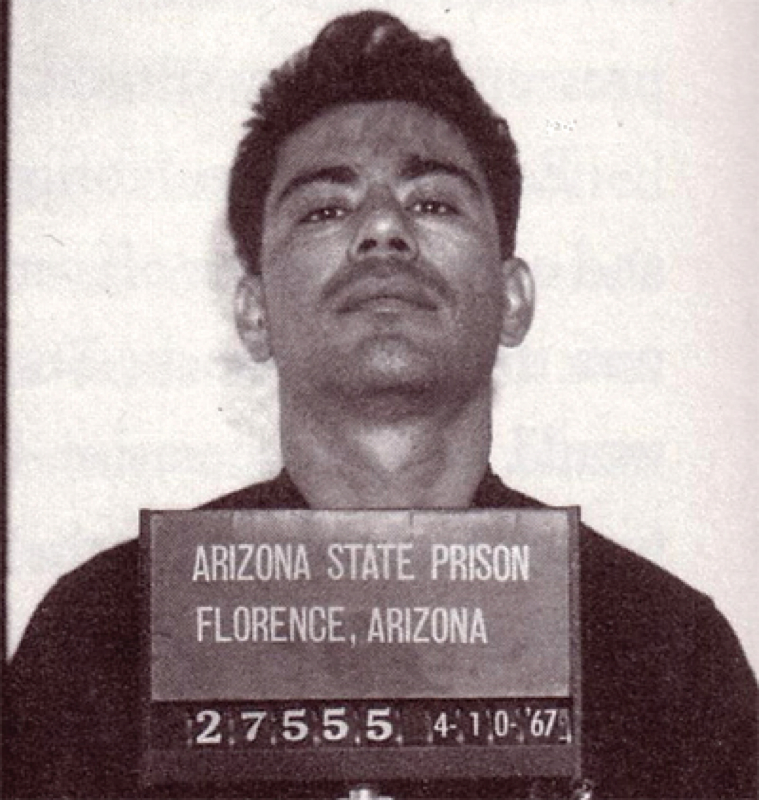

On March 13, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested under the charges of rape, kidnapping, and robbery. He was brought into the police station, where he was interrogated for two hours. During the interrogation, Miranda allegedly confessed to committing all crimes against him on a recording. However, he was not read his rights to remain silent and to have an attorney. When brought to trial, the prosecution’s only evidence was the confession, which was upheld in court. Miranda was found guilty of all charges and sentenced to 20 – 30 years in prison.

Procedural History

After his conviction, Miranda appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court. In 1965, the State Supreme Court affirmed the Superior Court’s decision where judgment was initially rendered against Miranda.

Thereafter, Ernest Miranda appealed to the United States Supreme Court where the case granted Certiorari. The case was argued in front of the Supreme Court on February 28th, March 1st and 2nd of 1966.

On June 13th, 1966, the United States Supreme Court decided to reverse the decision made by the State Court.

Issue

How far do the fifth amendment’s self-incrimination protection and the sixth amendment’s right to an attorney go when someone is accused of a crime, as applied through the fourteenth amendment?

Arguments by Petitioner

Arguments by Respondent

Decision

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Miranda in a 5 to 4 decision. The Supreme Court ruled that a citizen’s 5th amendment rights must not be violated and must be accessible no matter where the citizen is. This means law enforcement may not make claims that could incriminate suspects during interrogations with acknowledging them about their 5th amend right to not incriminate themselves. The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice Warren and was joined by Justices Brennan, Fortas, Douglas and Black. On the other hand, the dissenting opinion was written by Justice Harlan and was joined by Justices White and Stewart. The Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision.

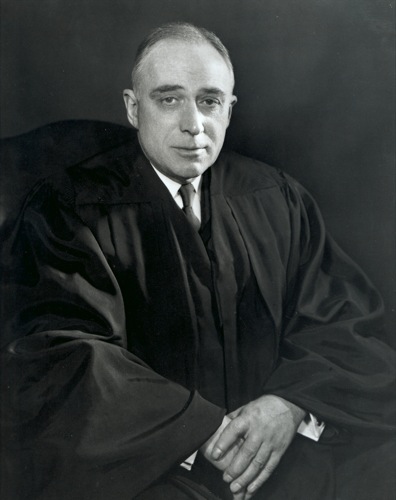

Majority Opinion (Warren)

Justice Warren wrote the majority opinion. The Supreme Court claimed, through the exclusionary rule, that statements obtained from defendants while being held in custody were only admissible in court if they were preceded by certain procedural safeguards, in order to protect the Fifth Amendment. Indeed, the accused must be made clearly aware of his privilege against self-incrimination and must have the possibility to exercise this privilege. These procedural safeguards include informing suspects of their right to remain silent, warning them that anything they say may be used against them in court, and notifying them of their right to an attorney, either chosen by the defendant or appointed to them if they lack the financial resources. Therefore, if the suspect indicates at any time that he wishes to remain silent or to consult with a lawyer, all interrogation must cease. The accused can also decide to waive exercise of these rights, as long as this decision is made willingly, consciously and intelligently. These measures aimed to prevent the police from using “third degree” stratagems, as Warren explained, which meant resorting to physical brutality or psychological coercion to extort confessions, and which was a clear infringement of individual liberty and human dignity.

Dissenting in Part (Clark)

Justice Clark’s opinion is dissenting in part. He argued that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Fifth amendment was too strict and added too many requirements to the admissibility of confessions in courts. He claimed this decision undermines the efficiency of law enforcement, for which custodial interrogation is an essential tool. Confessions shouldn’t be automatically excluded just because the police failed to inform the suspect of his rights. Instead, Justice Clark suggested to rely not on the exclusionary rule, but on the “totality of circumstances” in each case in order to decide whether a statement resulting from interrogation should be admissible in court.

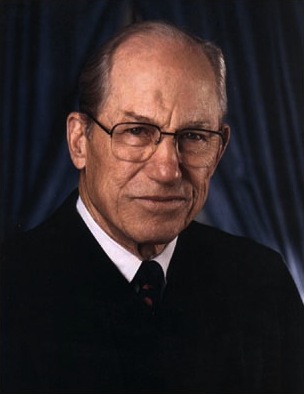

Dissenting Opinion (Harlan)

Justice Harlan wrote a dissenting opinion. He believes that the Court’s decision will not be effective in preventing police brutality nor other forms of coercion. He also claimed that the majority opinion’s interpretation of the Fifth amendment forbidding all pressure on the suspect was not backed by any constitutional precedent. Therefore, the Court’s view that the Fifth amendment requires suspects to be informed of their rights wasn’t supported by any legal precedent neither. Moreover, before this decision, the Court had already developed an effective approach to deal with the admissibility of confessions.

Dissenting Opinion (White)

Justice White wrote a dissenting opinion. He argued that the Fifth amendment forbids suspects to incriminate themselves only if they are compelled. He also disagreed with the Court’s opinion that custodial interrogation is inherently coercive. Finally, he criticized the consequences of such a decision, which he sees as impeding on the ability of the law to prevent crimes. Indeed, by making custodial confessions much more difficult to be admitted in court, he believes this decision will increase the likelihood of releasing criminals on the streets.

Full Text of Opinions

- Syllabus

- Majority Opinion (Warren)

- Dissenting in Part (Clark)

- Dissenting Opinion (Harlan)

- Dissenting Opinion (White)

Decision Analysis

Significance/ Impact

The significance of Miranda v. Arizona was that it’s not sufficient to have rights if you don’t know them. The police has to honor rights and make one aware of their due process. It was found that prosecution may not use statements arising from interrogation unless procedural safeguards were in place (an element of the exclusionary rule, which states that statements illegally obtained during an interrogation are inadmissible at trial). The purpose is to make sure the alleged suspect spoke on their own free will and were not coerced. The ‘Miranda Rights’ has created a specific procedure for cops to follow so that when individuals are informed of their rights, they are well aware of the statements they are saying, and that later, their statements can (if need be) be used against them in the courts without any statements being considered inadmissible. ‘Miranda Rights’ has also shown that there has to be a negative consequence if the police does not tell one their rights.

‘Miranda Rights’ do have some exceptions though. Although many other court cases have set a precedent for the exceptions, one in particular, NY v. Quarles (1984), set a precedent of the exclusionary rule that there is, however, a public safety exception to the ‘Miranda Rights’. This means that if one has created a threat to public safety, then the ‘Miranda Rights’ and exclusionary rule are null and void.

The precedent set in this court case was proof that the suspect was aware of his:

- Right to be silent

- Any statements may be used against him

- Has the right to have an attorney present

- Has the right to have attorney appointed to him

- May waive rights if done so voluntarily

- If attorney is requested, no further questioning until one arrives.

Second Timeline

Scholarly Commentary and Debate

Constitutional Provisions

- Fifth Amendment

- Self incrimination clause

- Due process clause

- Sixth Amendment

- Right to counsel

- Fourteenth Amendment

- Due process clause

Governmental Law or Action Under Review

The action under review was based upon the fifth amendment and an individual’s protection against self-incrimination – specifically when a suspect is interrogated by the police. So the question under review was, “Could the suspect be arrested upon his responses to the interrogation by the police, even if he was not notified of his fifth amendment rights?” Because Miranda was arrested upon a crime in which he was not notified of his 5th amendment rights, it was held that the prosecution could not use statements from an interrogation unless the suspect was notified of his rights prior to the interrogation.

Important Precedents

- Bram v. United States (1897)

- Brown v. Mississippi (1936)

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963)

- Massiah v. United States (1964)

- Escobedo v. Illinois (1964)

Important Subsequent Cases

- Doyle v. Ohio (1976)

- Edwards v. Arizona (1981)

- New York v. Quarles (1984)

- Colorado v. Connelly (1986)

- Illinois v. Perkins (1990)

- Pennsylvania v. Muniz (1990)

- Maryland v. Shatzer (2010)

Web Resources

McBride, Alex. “Miranda v. Arizona (1966).” PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_miranda.html

“Facts and Case Summary – Miranda v. Arizona.” United States Courts. http://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-miranda-v-arizona

Holland, Brooks. “Miranda v. Arizona: 50 Years of Judges Regulating Police Interrogation.” American Bar Association. http://www.americanbar.org/publications/insights_on_law_andsociety/15/fall-2015/miradavarizona_holland.html

“Miranda v. Arizona: Liberty and Justice for All.” Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vfv0ksDreFw

“Miranda v. Arizona.” Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Kx0aSkZN7Y

Academic Book, Articles and Law Reviews

Beechy, Melissa. “Miranda v. Arizona (1966): Its Impact on Interrogations.” Kennesaw State University (2014). http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=mscj_etd

Elsen, Sheldon H., and Arthur Rosett. “Protections for the Suspect under Miranda v. Arizona.” Columbia Law Review 67, no. 4 (1967): 645-670.

Taylor, Bryan. “You have the right to be confused! Understanding Miranda after 50 years.” Pace Law Review 36, no. 1 (September 1, 2015): 1-58.

Ulrich, Paul G. “Miranda v. Arizona: History, Memories, and Perspectives.” Arizona Summit Law Review 7, no. 1 (2013): 203-288. http://www.heinonline.org.ezproxy.gsu.edu/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/phnxlwrv7&start_page=203&collection=journals&id=231

Wrightsman, Lawrence S., and Mary L. Pitman. “The Miranda ruling : its past, present, and future.” Oxford University Press (2010).

Contributors

Spring 2017: Claudia S. Martinez Diaz, Marion Andreani, Lauren Jones, Usama Lakhani, D’vontis Arnold.

Tasks for Future Contributors

We encourage future contributors to conduct research on the following topics: arguments by petitioner, arguments by respondent, decision analysis, and scholarly commentary and debate. It is also highly suggested to read over our brief and edit whatever is deemed necessary to make it more well-rounded for the public. Specifically sections such as the summary, background, decision and analysis could be better addressed. It is also encouraged to add photos and media, for example videos to make this page more appealing to its readers.