One of the major projects that I will be working on this fall is a project coming out of the history department’s efforts to re-imagine the US history survey (2110). This is perhaps the key course offering of the entire history department. Certainly, it is the primary, and in many cases only, exposure that GSU students will have to history as an academic discipline. Two faculty members in the department, Rob Baker & Jeff Youngs, have been working for over a year on their version of the course, which will be a hybrid class featuring a custom-built and custom-written multimedia textbook. The course is being offered this fall for the first time as a hybrid course, meaning that students meeting physically only 1 time per week, using the other course period to engage with video segments, online activities (such as quizzes), and the traditional staple of 2110, reading assignments from a textbook coupled with a hefty dose of primary documents. As a SIF fellow, I’ll be helping primarily with editing ‘raw’ video segments, most of which take the form of conversations or debates between historians about important historical topics, adding visuals to the footage to make a more engaging viewing experience.

Today, though, I want to talk a little bit out the readings for Rob & Jeff’s version of 2110. Both the primary sources and the textbook itself exist as PDF files, which students access and read through D2l (Desire-to-Learn, GSU’s commercial class portal pages). Having all the readings available as PDF serves a number of very important purposes, not least of which is that they provide a much more convenient and flexible way of giving students free access to course material than the old standby, library reserves. Textbook costs, while not as outrageous in history as they are in many other disciplines, are still a significant expense for any college student, and even more so at schools like Georgia State, which educates an abnormally high percentage of students with very limited financial means.

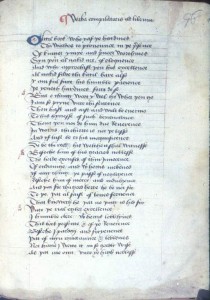

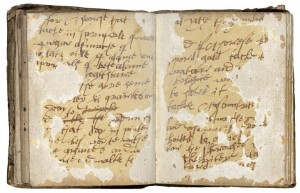

In the bigger picture, all of us now spend at least some time reading on PDF’s. For all practical purposes, academic journals are essentially now little more than part of the citation for a PDF file, and many of us are interacting with books this way as well. Even an early modernist like me mostly interacts with PDF facsimiles of old books, rather the real thing. There is little doubt that there are huge advantages to PDF’s. They are more convenient, more portable, and — take my beloved 16th and 17th books for example — much easier to get ahold of. The work I do would be almost impossible without PDF’s without long periods of travel, since most of the primary sources I need for my dissertation certainly aren’t available at GSU, and very few are even in the much better-stocked rare books libraries at major public or private universities in the southeastern U.S.

But for all their strength’s, PDF’s have significant disadvantages. Studies have shown that reading comprehension is lessened by interacting with material on a computer screen. I suspect that a lot of the reason for that is that PDF reading can easily be very passive. Good, well-trained readers can compensate for this. For example, I take pretty thorough notes in Zotero while I read material on PDF, which at least provides some of the advantages of writing/paraphrasing material that note-taking offers. But, many of the students in 2110 are not well-trained readers, and I worry that relying heavily of PDF’s might aggravate their worst habits as readers. In particular, it can discourage marking up texts, highlighting, underlining, making marginal notations, etc., all of which increase comprehension and make it easy to return to and reuse texts once they have been read.

Fortunately, there are ways around this. Even the basic adobe software needed to open PDF’s includes a highlighting feature and a ‘sticky’ note feature that can be used to make some kinds of notations on the PDF file. I know there are commercial software packages available as well that might offer more robust annotation features, especially the ability to write on PDF’s using a stylus (which might mimic some of the enhanced mnemonic advantages of a pen over typing). I have not personally used any of these, but perhaps some of my other SIFers may have a recommendation. If there is a standout product, perhaps GSU should consider adding it to the list of software it provides free or at reduced cost to students.

As a teacher, I think it is important that if we are going to us PDF files in the classroom we take the time to show students how to make notes on their texts, even if it is only the highlighting/sticky note options available through adobe acrobat. Many students will not know that these features exist, and may well use them if a few minutes of class time were spent familiarizing them with what they are and how they can be helpful. Perhaps it would even be worth requiring students to turn in their PDF’s. This would be a simple assignment that could yield useful information about how students are reading the assigned material, and give instructors an idea of how many of their students are picking up on the major points and arguments of the reading.

This is a simple little thing. But I think it is an important thing. Even a simple piece of software like a PDF viewer can be used more or less effectively, and in this case, meaningful gains in student comprehension and in their development as active and engaged readers might be possible with a small investment of class-room time.