As the Hoccleve project nears our first major milestone, the digital publication of an edition of Hoccleve’s holograph poems, we are beginning to ask questions about how to transform our XML into an HTML display. Thus, we are embarking on a graph design/display phase of our work. One of the things we have been discussing is creating data visualizations of the poems as an ornament to the edition. Most likely, these will be simple. Word clouds for instance. I have been asked to explore some options for this.

This is not something that I have done before, but it is something that I have been curious about as a tool for my own work. Because the plain text versions of the poems weren’t quite ready, I decided to take a little time to begin explore what might be possible, from a historical perspective, with data visualization tools.

I also figured it would make an interesting first blog post of the semester, even if at this point my foray into data visualization and data mining is completely amateurish. Even so, I am reporting on some early experiments using Voyant, a free web-based tool for textual analysis. I want to to see how it worked with early modern texts and with some of the documents I am using for my dissertation. This post is also offered in the spirit of a simple review of the software.

My dissertation is a study of relations of power between the English and Native Americans in colonial Virginia. For this reason, I decided to run William Hening’s old edition of the Colonial Statutes of Virginia into Voyant. Hening’s book prints most of the surviving documents from the legislative branch of Virginia’s colonial government, so this is essentially a book of laws. I was curious to see what textual/data analysis might be able to show about Indians as the object of legal proclamations.

Step one was quite simple. I went to the Internet Archives and copied the URL of the full text version of Vol. 1 of Hening’s Statutes (which covers the period between 1607 and 1660). In Voyant terms, this is a very small sample — only 233,168 total words, and about 21,000 different words. (I have put in several million while playing around, without any problem at all, so Voyant seems capable of handling large samples of text).

If you are using a modern book, with standardized spelling, these numbers should be essentially complete and usable. But the first issue with dealing with early modern texts in Voyant is that we are going to be dealing with texts written before standardized spelling. Voyant is counting “she” and “shee,” “laws” and “lawes” as different words. This is immediately going to make all the data less than 100% accurate.

For those of you not familiar with texts of early modern documents, look at this, for example. This is a randomly chosen page from The Records of the Virginia Company of London, which was published in an essentially diplomatic transcription (one that keeps as close as print will allow to the manuscript sources on which it is based)

You can see first off how difficult it would be to OCR this. Hening’s text is a much more user-friendly semi-diplomatic transcription, which is part of why I am using it as the main text for this blog post, but even it has some irregularities in the OCR full text generated by the Internet Archive based on its irregular textual conventions. But, Hening preserves original spelling, and this poses issues for running it through Voyant.

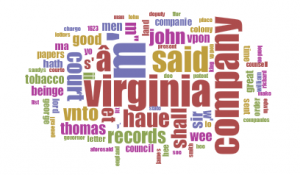

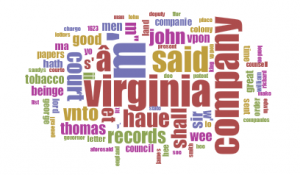

You can see this, visually as it were, on the word clouds. Here, for example, is a word cloud for Volume 1 of the Records of the Virginia Company of London. In order to screen out very common, but generally uninteresting words, I have turned on Voyant’s so-called “stop words” (words which are screened out from the word cloud).

As you can see, even with those turned on, the cloud is still rather cluttered with basic words, repeated words, and other oddities, because of variations in spelling:

Now, you can manually add stop words to Voyants list, and slowly purge the word cloud of oddities. That might work for something simple like making a word cloud, but its not going to solve the larger problems that early modern spelling present to data mining/analysis. One possible long term solution to this is another piece of software, called VARD 2, which I obtained this week but have not yet had the chance to learn. VARD 2 is designed to generate normalized spellings for early modern texts, making data mining more possible and accurate. Even with this tool, however, a lot of text preparation work is required in order to end up with a “clean” text.

And that is the first big lesson about data mining/visualization/analysis on early modern texts – they present issues about the ‘text’ that do not arise with modern typefaces, spellings, etc.

For now, though, since I’m just playing, I’m hoping to work around these rather than solve them. So, I go ahead an do something very basic by asking Voyant to track all the times the word “Indians” (in its modern, and most common early modern spelling) appears in the text. By asking Voyant to show me the results as a trend line, I can see the relative frequency of the word rise and fall over the course of Virginia’s statutes. Because the statutes are published in chronological order, they are also, conveneniently, a time line.

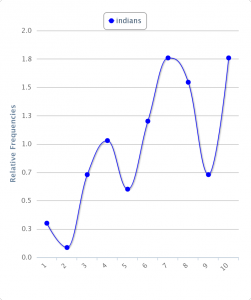

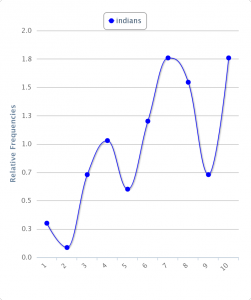

With the full text of Hening’s, a trend line of references to “Indians” looks like this –

Note that references to Indians spike at the end of the text, which in this graph is divided into 10 segments of equal length. This spike at the end is a reflection of another problem with the source text, the index and the rest of the prefatory material that surrounds the actual statutes themselves, which are the part of the book that I am interested in.

The only way around this is cutting and pasting – a lot of it. So, I hand-delete everything in the text that is obscuring my sample. This amounts to a lot of cutting. Without the index and introduction, the text drops from 233,000 words to 183,000.

Using this text, I run the trend line again, and the change is clear. Most notably, the “index” spike no longer appears.

The relative frequency of the word, however, is largely unchanged. In the ‘full’ version, the word Indians appears 9.74/10,000 words. In my ‘new’ version, 9.96.

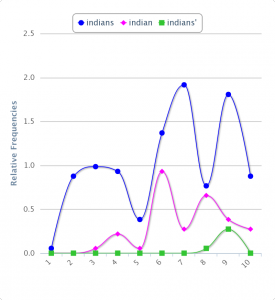

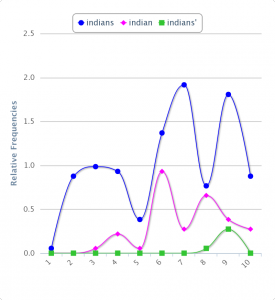

What do these charts show? Not a whole lot in isolation. What is more interesting is what happens when you begin to make this a comparative project by importing the second volume of Hening’s Statutes, which covers the period 1660-1682. This period is an important one to my dissertation for historiographical reasons. Most scholarship on Indians in Virginia has focused heavily on the period between 1607-1646, the “contact” era period when settlers and the Powhatan chiefdom were aggressively trying to establish their power over the other. These battles were largely decided by 1646, and with the decline of the Powhatan as a major power, historians of colonial Virginia have generally begun to rapidly loose interest in Indians, who go from central to bit players in narratives of Virginia’s history. This partially because historians become, around mid-century, interested in telling the story of the rise of slavery in Virginia, but partially because there is a sense that “Indian” history in Virginia is largely by that time.

Yet, references to Indians in Virginia Statutes increase in Volume 2, which covers 1660-1682. They now appear 13.53/10,000 words. Less than words like “tobacco” (25.97) and court (24.12), but more than “burgesses” (10.14) and king/kings/king’s (combined 10.23) and servant/servants (combined 11.00).

This is potentially interesting because it doesn’t fit with the impression of conventional historiography. Indeed, it suggests that Indians importance, at least in the eyes and words of the law, is increasing. By themselves, of course, the numbers don’t really mean anything. That’s where deep reading as opposed to computer assisted shallow reading comes into play. By they are an interesting numerical representation of an intuitive observation that helped shape my dissertation, which was initially prompted by a sense that historians had been too quick to turn their attention away from Indians as a subject in Virginia history. This little exercise in Voyant doesn’t itself mean much, but it does allow me to quantify that sense in a relatively easy way, by pointing out that Indians become more prominent in Volume 2 of Hening’s Statutes than in Volume 1.

It would be absolutely fascinating to see if this trend continues after 1682. But, that thought leads me to the next challenge I ran into in my early experiment in data analysis — finding source texts to analysis. As wonderful as Internet Archives and Google Books are, neither seems to have a copy of volume 3 of Henings Statutes. So, my curiousity about whether this trendline would continue is stymied by the lack of access to a text to import.

My aim in this post has been pretty modest. Mostly, it is a simple report of a couple of hours playing around with what for me is a new tool. It also points to the continuing resistance of early modern texts to data mining techniques, and to the reliance that people like myself, who are not going to be readily able to generate text files of huge books for analysis, on the vagaries of even extensive resources like the Internet Archive.

Will any of this factor in my dissertation? Who knows – these kinds of tools are still, I think, more commonly used by literary scholars than historians and as you can see from this post – they are not within the purview of my disciplinary training. At this point, I’m not even sure I’ve learned anything from my several hours of exploration, except that it was fun and that I’d like to spend more time with it, thinking about how to make it do more interesting work.

Have any SIF’s worked with these kinds of tools before and if so, with what kinds of results?