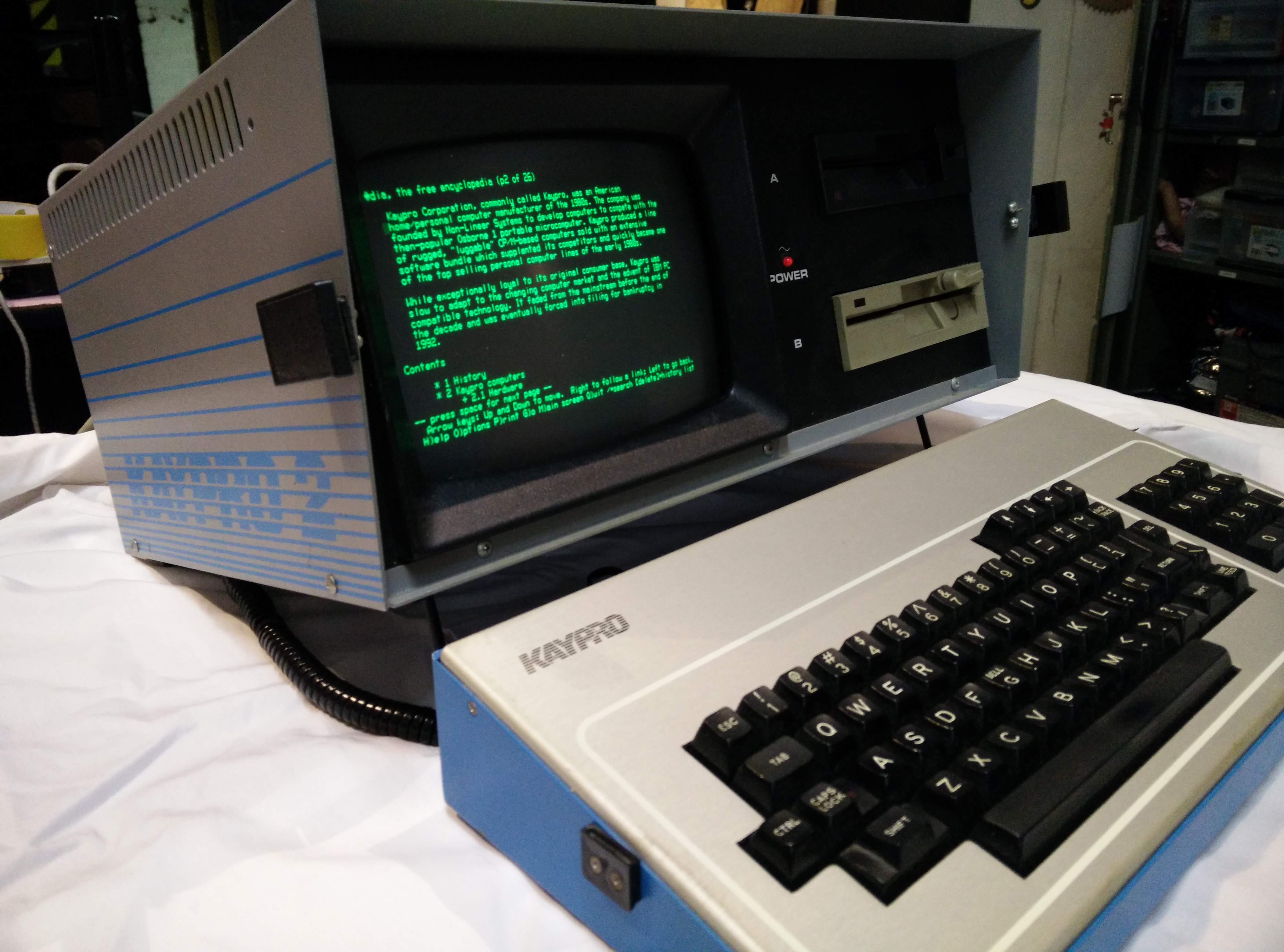

This semester, the Hoccleve Archive team has been steadily progressing towards a major goal, creating a searchable Lexicon out of a set of computer files, known as the HOCCLEX files, that were created over three decades ago. For a bit of perspective, consider that the work stations for cutting edge humanities computing projects at their creation looked like this.

First created in the early 1980’s as part of what was at the time a pioneering effort to bring computing power to humanist research, the HOCCLEX files are also a fascinating piece of the history of what we now call the Digital Humanities. It is that story I’d like to sketch today.

The HOCCLEX files were developed in the early 1980’s by Peter Farley, working under the auspices of an editorial team lead by D.C. Greetham. They contain semi-diplomatic transcriptions of the poetry found in Hoccleve’s three surviving holograph manuscripts (Huntington MS HM 111, Huntington MS HM 744, and Durham MS Cosin V.III.9). Each word in the transcription has been marked with a Middle English root form and tagged for grammatical and syntactical data including person, number, and part of speech. The original purpose of the HOCCLEX files was to create the raw data for a lexicon of the holograph manuscripts. Greetham proposed to use this lexicon to identify preferences in Hoccleve’s holograph manuscripts that could be used to normalize spelling variants and resolve accidentals in a critical edition of the Regiment of Princes, Hoccleve’s major poetic work. In a very real sense, the HOCCLEX files were the core of Greetham’s proposed edition, the key piece of the puzzle that he hoped would allow him to combine a Lachmannian base-text approach with a copy-text editorial approach.¹ Moreover, they were the medium through which Hoccleve’s authorial intentions, as displayed in the holograph poems, could be discerned and transferred to the Regiment, which survives in numerous manuscripts, but not in Hoccleve’s hand.

Greetham’s work proceeded far enough for him to publish several articles outlining how the HOCCLEX files would be used, and to inform Charles Blyth’s 1999 TEAMS teaching-edition of the Regiment.

However, Greethams’ proposed critical edition failed to materialize. After 1999, the HOCCLEX files, their purpose seemingly spent, might easily have been lost. Fortunately, Blyth kept not only the computer files but a wealth of materials, including microfilmed copies of most of the Hoccleve manuscripts and over 6000 handwritten collation sheets. In 2009, Blyth donated these items to Elong Lang, and they now serve as the core archival resources of the Hoccleve Archives project.

Over the past several years, SIF fellows have been working to make the HOCCLEX files accessible to scholars and to recreate the Hoccleve Lexicon in a more robust and, most importantly, public form. Unfortunately, the files were formatted for a now-lost piece of custom software, making them difficult to view and of limited view as working texts. In the first semester of the SIF program, back when we had essentially no clue about how to organize workflows, personnel, and projects, a team of SIFs successfully converted the

original HOCCLEX files into .TXT files, making them accessible to modern computers in a standardized format. An .XML transform soon followed. This transformation allowed us to make a teaching edition of the holograph poems available on our website, a simple, but useful edition that makes the poems accessible to students.

Since the creation of the original files, their potential utility has been amplifed by the subsequent coming of the digital age. Greetham’s original conception for the lexicon was to create a tool that would largely work behind the scenes to inform a printed critical edition. In contrast, our aim is to take advantage of the internet to bring the Lexicon to life in a digital format where it can serve as a public tool. As a web-based resource, the Lexicon, populated with data from the original HOCCLEX files, can function as a fully searchable and browseable research tool of use to Hoccleve scholars, students of the Middle English language in general, and serve as a key archival resource available to collaborators on the largest goal of the Hoccleve Archive, a digital critical edition of the Regiment.

Our goal this semester has been to create this resource, and (knock on wood here) we are on the brink of successfully launching a prototype. The computing team, with vital help from Jaro Klc, have created a JSON search capable of retrieving data from queries, and a user-interface is well on its way. The initial prototype will be limited in some respects – most notably, it will display an untranslated version of the grammatical mark-up, so parts of speech searches will unfortunately display in such user-friendly forms as ” ‘v1#adj%prp'” or “‘n[??FORM?CHK]'”. This is, ironically, because the mark-up language has proven as stubborn as the archaic computer files to parse, for reasons that (double irony alert!) have to do with authorial intention. The HOCCLEX files contain almost 250 different abbreviations for parts of speech, some of which are easy enough to understand, but many of which are ambiguous ( ‘n#propn[NOT-MED]’), seem to be human errors ( ‘ende’) or are just plain head scratchers. Unless we can find the key to them, we may need the services of a seriously talented linguist/grammar nerd to help us replace the abbreviations with more user-friendly terminology. As someone who is always looking for the angle of what is humanist about the digital humanities, here you have it: in the end, we need not only computing skills but the lowly skills of a grammar nerd, much less valued in society, but crucial to the success of our project.

That is an issue for another day, however. It’s a humbling and amazing thing to be working on a project that was started before most of the team members assigned to it were even born. In the meantime, the internet has made its powerful presence felt in the horizon of possibility that guides us. What began as an essentially private database, certainly one that would inform public documents and which gave rise to peer-reviewed articles, but which nevertheless stayed behind the scenes because there was no easy means to make it public, will soon be accessible by students and scholars around the globe thanks to the power of the web.

¹ D.C. Greetham, “Normalisation of Accidentals in Middle English Texts: The Paradox of Thomas Hoccleve,” Studies in Bibliography 38 (1985): 127.