As I discussed last week, one of the things I find most compelling about the digital humanities is the way they bring together communicative technologies from various historical epochs, creating a new medium through which some of the basic humanistic skills developed in the renaissance can continue to flourish, in the process revitalizing them and perhaps reminding a higher-education industry that is currently infatuated with high-tech, with STEM fields, and with chasing the shiny and the new, of the enduring — I would even suggest foundational value — of the humanities to knowledge.

That, however, is a bigger nut than I want to crack today. Instead, I want to focus on one teeny example of a rather un-sexy technical skill, paleography (the reading of old handwriting), and how important it is to some of the most interesting and sexy digital humanities projects being undertaken today. In the last few years, very large amounts of manuscript material from the early modern era has been scanned and made available on the internet. Yet, much of that material is largely illegible. Posting it to the web has made it accessible, which is a massive step in the direction of the democratization of knowledge. But simple availability is very different from legibility – much of this material remains for all intents and purposes inaccessible, despite being only a google search away. OCR software has enough trouble with early modern printed texts (the recent project to transcribe the entire corpus of Early English Books Online has resorted to paying humans to make transcriptions of PRINTED texts because OCR technology is too inaccurate), and with manuscripts, or with hybrid-forms such as annotated books, displaying artifacts is really only the beginning of the work necessary to make them useful to researchers, especially undergraduates and non-specialists, and to data-miners and other computer-assisted researchers.

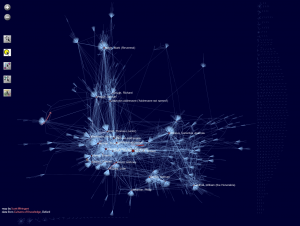

Let me just cite one example of how 21st century communicative tools intersect with early modern ones. Oxford’s University’s Cultures of Knowledge project, which is collecting metadata from what will eventually be literally hundreds of thousands of early modern letters, is creating amazing visual representations of early modern correspondence networks like this:

Behind the fancy graphics, however, is an immense amount of bibliographic and paleographic legwork – people have to read the letters, cataloging them, and identifying names and other key pieces of metadata that make these maps possible. For the most part, this needs to be done by people who can read the original manuscript letters, very few of which have been made legible for automated data-mining.

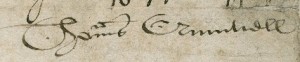

To make that map, in other words, you have to be able to read this: