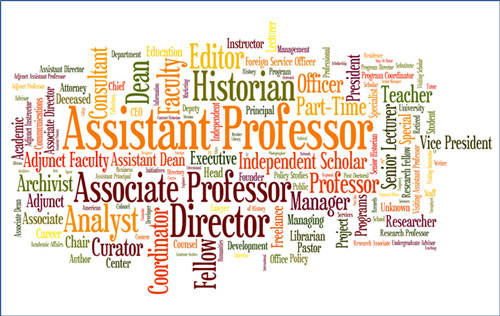

Jim Grossman’s day-long presentation was a thoughtful and very thorough account of the current state of PhD training in the humanities and an equally well-considered plan to improve career outcomes for humanists, especially those who end up in the vast contingent labor pool on which universities depend. At the heart of his talk were two key ideas. The first was that the problem is not one of oversupply. He rejected the commonly expressed argument that the answer to the shrinking number of tenure track faculty jobs is to shrink PhD programs, refusing the logic of tackling the statistical disparity between academic jobs and PhD’s on the supply side. Instead, he advocated shifting the conversation to what he calls “under-utilization” and redefining those outcomes that PhD programs identify as “successes.”

For me, at least, the virtue of this term is that it identifies the tragedy of the many talented, well-trained, smart and ambitious people who end up stuck in the vast pool of exploitative adjuncting jobs, shuffling around in the only slightly less cruel VL, VAP pipelines, or holding on to academia in other temporary jobs. Finding better outcomes for these people is, I think, the key to Grossman’s other main point, that we need to redefine success. In my mind the key to doing so is to switch metrics – instead of measuring success in terms of how many people get tenure track jobs, we ought instead to define success in terms of measurable declines in the number of folks stuck in the pool of academic contingent labor.

At GSU’s history department, we have tons of room for improvement on this statistic. Our PhD’s are twice as likely as those from other universities to end up on the margins of university teaching: almost 33% of our PhD’s are toiling outside the tenure track several years after earning their degrees. Nationally the average is about 15%. We are, frankly, below average both in terms of getting students onto the tenure track AND at getting them out of the contingent labor pool. Moreover, the percentage of our PhD’s who are employed “outside the professorate” is also below average.

When we think about improving these numbers, I think we should be honest about the fact that increasing our “placement” of students in the tenure track is going to be very difficult,not because of the quality of the program or students here but because the number of tenure lines is in free-fall and because history is a particularly hierarchical hiring discipline, with a very small handful of programs holding near monopolies on the market. There are, of course, strong arguments to be made that faculty and professional organizations ought to be putting real effort into reversing at least the first of those trends. I personally find the AHA’s readiness to concede the point that improving opportunities within academic is doomed a bit disappointing, even as I understand that the decline of the academic job market is caused by very well-entrenched and formidable economic, political, and social changes that, frankly, don’t look like they are going to do much besides worsen in the near future. Despite these trends, I think there is a case to be made that developing a distinctively focused PhD program at GSU may, at least on the margins, help our students do better on the traditional job-market by giving their education a focus and an angle that will differentiate them.

More significantly, we can and should be doing much better at providing an education that can take people out of the contingent labor pool and into other forms of professional employment. As Grossman emphasized, many of these jobs are within the university, in the form of (in truth still scarce) technology focused “alt-ac” jobs, or the much more common administrative jobs which modern universities seem to generate in nearly limitless supply. Putting aside questions about the relationship administrative bloat and the decline of tenure track lines, administrative work is a growth field with several advantages for history PhD’s. Universities value PhD’s, for one thing, and more than a few of us are in graduate school because we enjoy the atmosphere and perks that come from being employed by a university. Moreover, and I say this as someone who has spent a lot of time over the past six years working with administrators at GSU, much of the work they do is both immensely important, intellectually satisfying, and engaged (albeit at different levels) with questions of research, pedagogy, and activism that most PhD candidates love.

Grossman made several specific recommendations designed to ease pathways into this kind of work, such as floating the idea that PhD funding packages should include semesters devoted to academic work. This is a good idea, but I think the kinds of program we are looking towards, in particular the project management aspects of the SIF program, go even further in preparing PhD’s to perform administrative work. It’s also worth noting that there is no reason for current grad students in the department to wait on the department to build these skills. The university is full of options, both volunteer and paid, for grad students to engage with administrative work. Very few currently do so, in part because they are socialized to consider such work as a sideline that takes away from their “real” work.

Outside the academy, jobs abound, but we have a problem here of graduating students who feel unprepared for any work other than teaching. I hear this again and again from friends in the program. Many of these people will find themselves trying to hang on, working for peanuts teaching survey courses over and over before they find a path to work that better compensates them for their high level of training. One of the critiques of the project of building pipelines out of the academy is that it contributes to the commodification of intellectual life and the neo-liberalization of the economy. These are not entirely groundless critiques, but it is equally true that the way we (both at GSU and nationally) are training our grad students NOW leaves many of them trapped in low-wage, contingent labor sectors of the university world, and thus that they are already victims of those very forces. It is these folks, the 33% who are hanging onto the margins of academia, are those whom we are most failing, and who stand to benefit the most from redefining success.