Thesis: The built environment of Auburn Avenue looks the way it does today from its long history of segregation and its cultural representation of Civil Rights

Topic 1: Segregation of Auburn Avenue, making it the most successful black American street in the world.

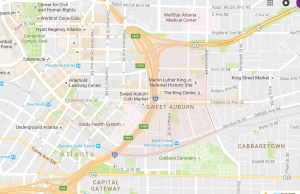

Map of Sweet Auburn District

“Sweet Auburn.” Sweet Auburn. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Early Segregation on Auburn Avenue

In 1900, businesses and professional firms at this end of Auburn Avenue were primarily White-owned and segregated, including United Investment Corporation Holding, Equitable Credit Union, and the Southern Belle Telephone and Telegraph Company. Within the next ten years, African American Peyton Allen and James Spratlin integrated this block of Auburn Avenue. Spradlin established the Atlanta Steam Dye and Cleaning Company. Alan, a teacher and an Atlanta University alumnus, opened a law office and advocated equal rights for African Americans. Atlanta’s streetcars were segregated by ordinance after 1890, prompting black citizens to boycott the trolleys around the turn of the century. Men such as Alan rode bicycles rather than sit in segregated streetcars, but they were unable to reverse the trend toward legislated segregation.

“Early Segregation On Auburn Avenue Marker – Historic Markers Across Georgia.” N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2016.

Golden Era Of Sweet Auburn

Originally called Wheat Street, the road was renamed in 1893 at the request of white petitioners who believed Auburn Avenue had a more cosmopolitan sound. During the next two decades, as restrictive Jim Crow legislation was codified into law, the city’s African American population became confined to the area between downtown and Atlanta University and to neighborhoods on the city’s east side, known today as the Old Fourth Ward. It was during this period that Auburn Avenue first achieved prominence as a commercial corridor and became home to the city’s emerging black middle class.

Originally called Wheat Street, the road was renamed in 1893 at the request of white petitioners who believed Auburn Avenue had a more cosmopolitan sound. During the next two decades, as restrictive Jim Crow legislation was codified into law, the city’s African American population became confined to the area between downtown and Atlanta University and to neighborhoods on the city’s east side, known today as the Old Fourth Ward. It was during this period that Auburn Avenue first achieved prominence as a commercial corridor and became home to the city’s emerging black middle class.

Although

The old Atlanta Life Insurance building, pictured in 2005, is boarded up on Auburn Avenue. Established by Alonzo Herndon in 1905, Atlanta Life was one of three financial institutions, all headquartered in the Sweet Auburn district, that served the black middle class in Atlanta before the civil rights movement.

Atlanta Life Insurance

composed mostly of small businesses, Auburn Avenue was also home to what historian Gary Pomerantz describes as Atlanta’s “three-legged stool of black finance.” The first of these institutions was founded by Alonzo Herndon, a former slave who became the city’s first black millionaire. After earning a modest fortune as the owner of a barbershop on Peachtree Street, Herndon founded the Atlanta Life Insurance Company in 1905. Six years later an enterprising Texan named Heman Perry formed a second black insurance company, Standard Life. Citizens Trust Bank formed the third leg of the city’s black financial stool, extending credit to black homeowners and entrepreneurs who were underserved by the city’s white lending institutions. Because Auburn Avenue’s financial institutions amounted to a consolidation of African American wealth unique for its time, black Atlantans referred to the street as “Sweet Auburn.” Coined by John Wesley Dobbs, a civic leader and the neighborhood’s unofficial “mayor,” the name reflected the avenue’s prominence as a national center of black commerce.Auburn Avenue was not simply a place to do business. Black Atlantans worshipped at Auburn’s many churches, including Ebenezer Baptist Church, where three generations of Martin Luther King Jr.’s family were pastors, and Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; dined at the legendary Ma Sutton’s; and spent late nights listening to ragtime at the famous Top Hat Club (later the Royal Peacock). The National Association for the Advancement

Auburn Avenue was not simply a place to do business. Black Atlantans worshipped at Auburn’s many churches, including Ebenezer Baptist Church, where three generations of Martin Luther King Jr.’s family were pastors, and Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; dined at the legendary Ma Sutton’s; and spent late nights listening to ragtime at the famous Top Hat Club (later the Royal Peacock). The National Association for the Advancement for Colored People (NAACP), the Odd Fellows, the Masons, and the National Urban League maintained offices on Auburn Avenue, which was also home to the nation’s first successful black-owned daily newspaper, the Atlanta Daily World. Whether for work or play, Auburn Avenue was the center of African-American life in Atlanta.

“Auburn Avenue (Sweet Auburn).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2016.

Topic 2: Civil Rights Movement

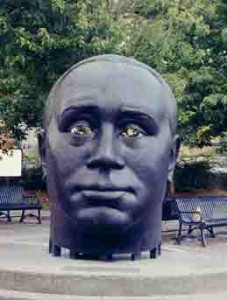

John Dobbs

Dobbs fervently believed that African American suffrage was the key to racial advancement. He announced a goal of registering 10,000 black voters in Atlanta and preached the importance of voter registration in Masonic halls, in African American churches, and on street corners. Dobbs also founded the Atlanta Civic and Political League in 1936 and, with attorney A. T. Walden, cofounded the Atlanta Negro Voters League in 1946. Both of these leagues advocated voter registration and black political unity.

Due largely to Dobbs’s efforts, African Americans achieved two significant political victories in the late 1940s. In the spring of 1948 Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield fulfilled a promise he had made to Dobbs by hiring eight African American police officers. Although they could patrol only black neighborhoods and could not arrest whites, the hiring was a significant challenge to segregation. The following year Hartsfield fulfilled another campaign promise by installing street lamps on Auburn Avenue, the center of Atlanta’s black community. Both of these achievements served to solidify Dobbs’s position as a leader. (Dobbs himself coined the term “Sweet Auburn,” an expression of the area’s thriving businesses and active social and civic life.)

During the 1950s Dobbs continued his work toward African American equality. He constantly pressed Hartsfield to fulfill other promises made to the black community. Dobbs’s influence began to wane, though, as the decade ended and a younger generation of African American leaders emerged at the forefront of the civil rights struggle. By this time he was suffering from arthritis, often unable to get out of bed.

“John Wesley Dobbs (1882-1961).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2016.

“Jwd_headft.jpg (JPEG Image, 259 × 343 Pixels) – Scaled (88%).” N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Martin Luther King Jr

During the less than 13 years of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership of the modern American Civil Rights Movement, from December, 1955 until April 4, 1968, African Americans achieved more genuine progress toward racial equality in America than the previous 350 years had produced. Dr. King is widely regarded as America’s pre-eminent advocate of nonviolence and one of the greatest nonviolent leaders in world history.

Drawing inspiration from both his Christian faith and the peaceful teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. King led a nonviolent movement in the late 1950’s and ‘60s to achieve legal equality for African-Americans in the United States. While others were advocating for freedom by “any means necessary,” including violence, Martin Luther King, Jr. used the power of words and acts of nonviolent resistance, such as protests, grassroots organizing, and civil disobedience to achieve seemingly-impossible goals. He went on to lead similar campaigns against poverty and international conflict, always maintaining fidelity to his principles that men and women everywhere, regardless of color or creed, are equal members of the human family.

Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Nobel Peace Prize lecture and “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” are among the most revered orations and writings in the English language. His accomplishments are now taught to American children of all races, and his teachings are studied by scholars and students worldwide. He is the only non-president to have a national holiday dedicated in his honor, and is the only non-president memorialized on the Great Mall in the nation’s capitol. He is memorialized in hundreds of statues, parks, streets, squares, churches and other public facilities around the world as a leader whose teachings are increasingly-relevant to the progress of humankind

“About Dr. King | The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change.” N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

“MTE5NTU2MzE2MjgwNDg5NDgz.jpg (JPEG Image, 1200 × 1200 Pixels) – Scaled (25%).” N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Historic King Center

Established in 1968 by Mrs. Coretta Scott King, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change (“The King Center”) has been a global destination, resource center and community institution for over a quarter century. Nearly a million people each year make pilgrimage to the National Historic Site to learn, be inspired and pay their respects to Dr. King’s legacy.

Both a traditional memorial and programmatic nonprofit, the King Center was envisioned by its founder to be “no dead monument, but a living memorial filled with all the vitality that was his, a center of human endeavor, committed to the causes for which he lived and died.” That vision was carried out through educational and community programs until Mrs. King’s retirement in the mid-1990’s, and today it’s being revitalized.

As we move into the second decade of the 21st century, the King Center is embarking on a major transformation into a more energetically-engaged educational and social change institution. Supported by our Board of Directors and an infusion of new thinking, the King Center is dedicated to ensuring that the King legacy not only remains relevant and viable, but is effectively leveraged for positive social impact.

In short, the King Center is repositioning to meet the challenges and opportunities of today. Squarely-focused on serving as both a local and global resource, the King Center is dedicated to educating the world on the life, legacy and teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., inspiring new generations to carry forward his unfinished work, strengthen causes and empower change-makers who are continuing his efforts today.

Plans include a state-of-the-art renovation to the King Center’s Atlanta campus, the preservation and digitization of our one-of-a-kind archives, the launch of an innovative digital strategy and conference series to bring the King legacy to a modern audience and the development of new programs and partnerships that further Dr. King’s work in sustainable, measurable ways worldwide. Through such efforts, the King Center can rise to its true potential as a beacon of hope and progress, to a world that still desperately needs Dr. King’s voice and message.

“About The King Center | The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change.” N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

“m1g_martin_luther_site.jpg (JPEG Image, 350 × 467 Pixels) – Scaled (64%).” N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Topic 3: Declination of Street due to Historical Preservation

Silver Moon opened in 1904. It was one among many businesses run by African-Americans, for African-Americans, along Auburn Avenue. During the period of segregation this street was called the “richest Negro street in the world.” The street existed because of the bleak realities of segregation, but in those days the corridor had a vibrant feel.”This was a street full of people on Friday and Saturday nights. If you were in a car it would take you perhaps 15 or 20 minutes to go a block,” recalls Wellington Cox Howard, a small-business owner on Auburn Avenue.

“This was a street full of people on Friday and Saturday nights. If you were in a car it would take you perhaps 15 or 20 minutes to go a block,” recalls Wellington Cox Howard, a small-business owner on Auburn Avenue.

2010: Sweet eats = Sweet success

When Howard first arrived in Atlanta in the 1960s he made a beeline for the street. He had his first meal on Auburn, resided on the street, and when he graduated from college in 1970s, he decided to open his insurance business there.

But by that time, change had already arrived on Auburn. Howard recalls telling a friend about his decision to open up shop there.

“He said why do you want to go to Auburn Avenue? He said the city has integrated. He said we’ve all left.”

Before integration, Howard says, Auburn was a city unto itself. African-Americans would come here for doctor’s appointments, they’d come for entertainment, they’d come for banking and to start large construction projects. When integration came, African-American businesses spread throughout the city and the corridor lost much of its vibrancy.

This year, for the second time, the Sweet Auburn District was listed as endangered by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a private nonprofit organization. This designation does not mean automatic funding for improvements, but the group says the attention often galvanizes efforts at preservation.

Sweet Auburn’s designation is somewhat unusual, because sites normally aren’t listed more than once. Since the initial designation, residential options have improved on the corridor, the group said, but “the commercial area concentrated on Auburn Avenue has not fared as well.” The concern is that without greater resources devoted to planning and preservation, many buildings could be lost along with the history they hold.

Along the corridor, news of the designation passed with mostly tepid curiosity. About a half-dozen local business owners CNN spoke to expressed surprise about the news but remained hopeful. Many spoke about recent positive changes they’ve seen, like a streetcar project that’s breaking ground with federal funds, and wondered whether the designation might spur more positive changes.

Councilman Kwanza Hall, who represents this district, has taken the news quite seriously. Hall, whose parents were civil rights leaders, spent many days on Auburn as a child.

“There’s a very rich treasure in terms of African-American history,” Hall said, rattling off a long list of buildings and their historical significance. For Hall the endangered designation necessitates a big response. He calls it a “Marshall Plan”: a concept to revitalize the community by bringing all the disparate interests on board.

But Hall is not naïve. “It’s not easy to move multiple entities, all who have their own boards and organizational goals that are sometimes in conflict,” he said. Hall is well aware that for historic preservation to get buy-in from existing landowners, there must be a clear incentive for everyone.

Up and down the street that message is well-received. Owners of new and old businesses alike stressed the need to respect history but not to let it get in the way of progress.

Windsor Jones, who owns Sweet Auburn Bread Co. with his mother, said they’d moved to the street five years ago because of the history. The bakery routinely gets tourists wandering down from the Martin Luther King Jr. Center, a major point of pride for the business that turns out muffins and sweet potato cheesecake.

Also nearby are the home were King was born and Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he was pastor. Still, doing business on this street has drawbacks. Jones shoos away a woman asking for change as he squints out the window looking at the ruins of a building across the street.

“They’ve already torn down some buildings,” he says, “and I understand why they want to save some, but some of them are eyesores.”

Around the corner from Jones’s bakery, a lush green garden provides a vivid picture of how the legacy of this corridor can live on even with radical change. Rashid Nuri and Eugene Cooke run the space here known as Wheat Street Gardens, and turn out beautiful organic produce. The small but productive farm bustles with activity. There’s a summer camp here and the garden just got funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to train urban farmers.

Cooke pauses from a lesson in harvesting to explain how their work fits in with the area’s history.

“Every human definitely deserves to eat good food, so it is absolutely in that lineage of human rights issues,” he says.

This view is reinforced by the landscape. Beyond the rows of peppers and sunflowers, historic buildings peek out, buildings that keep Cooke focused on his mission of spreading social justice through good food.

Despite the visible challenges on this street — the empty storefronts and a handful of rundown buildings — Hall says he thinks this is actually a good time for Auburn. It’s a view shared by many who work on the street every day.

Right now, federal dollars are flowing in for the streetcar project, and many see the future for this street with the neighboring Georgia State University continuing to expand its downtown footprint. Hall says now is the time to move forward with new projects while keeping alive the memories of this street’s role during segregation, and its famous residents’ roles in ending it.

Conclusion: Auburn Avenue built from its politics and civil rights history.

Although economically governed by the restrictive Jim Crow Laws, from the 1920’s through the 1940’s Sweet Auburn Avenue was at the height of its social vigor and the present day buildings reflect this energy. After this golden era, the west side of Atlanta around the Atlanta University Center became a more fashionable area to locate an African American business or residence. Desegregration in the 1960’s furthered an exodus of people and energy from the area, leaving the street somewhat depopulated as it is today.