Atlanta, the most populous city and also the U.S. state of Georgia’s economic and cultural nucleus, arose out of the ashes of the Civil War in 1837. Located at the end destination to two major railroad lines Atlanta was quickly established as a metropolis hub. The city of Atlanta, although diverse with heavy spacial connotations of hip-hop culture, trap culture, and the civil-rights movement and other aspects of specifically black, minority culture, promotes the gentrification and thus the evanescence of a primary characteristic of the city’s rhetoric via neighborhood rehabilitation. Atlanta is also known colloquially as the “capital city of black america” or “black mecca” and this is particularly because of its status as as a hub for black productivity especially in terms of culture. In fact, 80 percent of Georgia’s African-American population is concentrated in the Atlanta Metro area. Atlanta’s accretion of African-Americans can be directly attributed to the prevalence of the slave trade in Antebellum South. In 1850 the city of Atlanta had 493 enslaved blacks and 18 free-blacks. By the year 1870 African-Americans comprised 46% of the total population of Atlanta (21,700) this ratio of blacks to other races remained steady well into the 19th century.

In accordance to the prevalence of African-Americans in the city, aspects of African-American culture were and are still today heavily associated, rhetorically, with the city. Hip-Hop and Trap culture and the Civil-Rights movement all are major characteristics of African-American culture and Atlanta alike. The commonality between the two subcultures and the historical movement combatting Jim Crow south is that they are exemplary of the African-American struggle. The city of Atlanta, like many others in the south is no stranger to the promotion and maintenance of gentrification and other aspects of Caucasian socioeconomic superiority. The Civil Rights Movement was the uprising of African-American’s in the south against racist and segregationist Jim Crow laws.

Atlanta’s role as an epicenter of the Civil-Rights Movement as a whole is apparent with its status as the birth and living place of perhaps the most prevalent and well know Civil Rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr and city that houses many memorials to the Civil Rights Movement and African-American culture in the city such as the King Center and the Apex Museum. Hip-Hop and its subcategory of Trap which was created in Atlanta is specifically related to and talks about the struggle of “trapping”(to sell and or cook) drugs in metro Atlanta’s lower class, demographically African-American ghettos. The history of Atlanta as a travel stop or major destination and Atlanta’s abundance of highways, interstates, explains it’s prevalence in drug trafficking and how ‘Trap’ music came to be. Trap music is a form of rap music that relies heavily “the sound of the brass, triangle, triplet hi hats, loud kicks, snappy snares and low end 808 bass samples that are used when composing tracks”. The percussion samples of choice when making trap music are usually originate from the Roland T-R 808 drum synth (RunTheTrap.com). The rise in the mainstream media popularity of aspects of African-American culture coming out of Atlanta has worked to create an Afro-centric spacial rhetoric for the city and catalyzed its coining as a “black mecca.

This is especially true of Hip-Hop and Trap culture which according to Noisey Atlanta rose out of Atlanta’s Zones 1-6 and has since then rose to global popularity with songs like “Panda” by Trap artist Desiigner and Future’s trap album reaching number 1 status on Billboard’s Top 100 Charts. With the first line of the Top 100 song in America right now being “I got broads in Atlanta” Atlanta is getting a lot of popular media attention and the artists themselves as well as the city are capitalizing on Atlanta’s spacial rhetoric as an epicenter for black culture (Forbes). Despite this, Atlanta is aiding in the dissapearance of this inherently lower socio-economic Afro-centric culture through promoting the gentrification of this city with inherent Afro-centric connotations. Atlanta is accomplishing this architecturally through neighborhood rehabilitation. Neighborhood rehabilitation also known as urban renewal, or even urban revitalization is roughly defined as “a natural process through which the urban environment, viewed as a living entity 1, undergoes transformation. “As the years pass, transformations take place, allowing the city to constantly rejuvenate itself in a natural and organic way” (mcgill.ca). Within the boundaries of metro Atlanta or greater Fulton county, examples of this gentrification are apparent everywhere. In my own research I visited CabbageTown Atlanta, a little town adjacent to Oakland Cemetery located to the east of downtown Atlanta. Cabbage town is a clear example of a town within Atlanta that went through some neighborhood revitalization. Cabbage town started off as a the location of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill and housing for the factory workers. Since then these houses for poor factory workers have been partially torn down and converted into lofts or business offices. The juxtaposition of traditional southern homes and bungalows with wrap around porches and A-frame roofs sitting perpendicular and parallel to high end lofts exemplified the change in not only architectural styles, but the inherent and insidious hinting towards the change in socio-economic demographic makeup of the area.

The Kirkwood area of Atlanta has also gone through some neighborhood revitalization that has resulted in a racial divide and then the over taking of a traditionally black, minority neighborhood, as Caucasians moved into these areas like Edgewood, Kirkwood, and other East Atlanta towns prevalent in the “Trap Culture” of Atlanta: “You can still find small houses in need of repair, older black men hanging out on front porches, the occasional homeless addict wandering the streets. Yet they share space now with cafes, clothing galleries, expensively renovated homes and factories converted into upscale lofts. Almost any day of the week, one finds young white couples pushing baby strollers or checking out the progress of the new Japanese restaurant that’s going in…White newcomers are picking up houses and condos in Cabbagetown and Midtown, in Edgewood, Kirkwood and Castleberry Hill, up at the new Atlantic Station project and downtown in mixed-income developments that have replaced some of the most legendarily dysfunctional public housing in America. “It has become classy,” says local political consultant Angelo Fuster, “to live in the city.”

There is really only one way to put it: Atlanta is becoming whiter, and at a pace that outstrips the rest of the nation. The white share of the city’s population, says Brookings Institution demographer William Frey, grew faster between 2000 and 2006 than that of any other U.S. city. It increased from 31 percent in 2000 to 35 percent in 2006, a numeric gain of 26,000, more than double the increase between 1990 and 2000″ (Governing.com). With gentrification comes the ideal that the “traps” and the “ghettos” of the city that house mostly African-Americans of lower socio-economic stature are blemishes on the face of the city of Atlanta, although these areas that are being stripped of their original homeowners and image, are also being stripped of the black culture that is so often attributed to Atlanta. It is not only the understandably negative or problematic connotation of trap and drug culture that is being slowly snuffed out by the white paint of gentrification, but also areas key to African-American Civil Rights, like Auburn Avenue (the birth place, burial place, and location of Ebenezer Baptist Church of Martin Luther King’s) is slowly but surely facing white-washing as these neighborhoods are being changed over to welcome those of a higher socio-economic stature, with percentage of white collar workers in these areas averaging around 60.2% (points2homes.com).

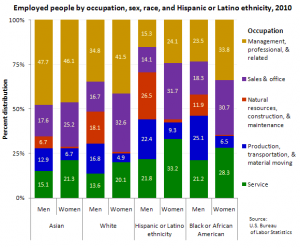

While Atlanta is not seemingly directly targeting African-Americans, it is statistical knowledge that Caucasians possess higher paying jobs to be able to live in these rehabilitated or revitalized areas with White males averaging at about 34.8% with managerial or professional jobs and 16.7% with sales and office professions. Whereas on average, African-American males sit at about 23.5% with professional or managerial jobs and 14.1% with sales or office professions (bls.gov). Although, while the morphing and changing of a neighborhood overtime is natural, neighborhood revitalization is problematic because a lot of the time it results in the uprooting of a people and the complete loss of historic neighborhood characteristics.

Other examples of this are popping up everywhere as urbanism continues to promote the building up of its spaces. In regards to Atlanta, because it has such a heavy spacial connotation of African-American culture (enough for it to be mistakenly coined as a black mecca) this neighborhood rehabilitation or gentrification is resulting in the a literal white-washing or white out of a crucial part of Atlanta’s overall culture and aesthetic.

Bibliography

“Charts.” Billboard. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

Caldeira, T. P. R. “Fortcified Enclaves: The New Urban Segregation.” Public Culture 8.2 (1996): 303-28. Web.

“Atlanta and the Urban Future.” Governing Magazine: State and Local Government News for America’s Leaders. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

Levatino, Adrienne M. Neighborhood Commercial Rehabilitation. Washington: National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials, 1978. Print.

“Chapter 1: Urban Renewal.” Home Page. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

Richard Lloyd, “Urbanization and the Southern United States,” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (2012): 483–506.

The Civil Rights Movement.” The Civil Rights Movement. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

“What Is Trap Music? Trap Music Explained | Run The Trap.” Trap Music Blog Run The Trap The Best Hip Hop EDM Club. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

“Earnings and Employment by Occupation, Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2010 : The Economics Daily : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

United States. National Park Service. “African-American Experience–Atlanta: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

United States. National Park Service. “African-American Experience–Atlanta: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.

“Segregation’s New Geography: The Atlanta Metro Region, Race, and the Declining Prospects for Upward Mobility.” Jjoh238. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016.