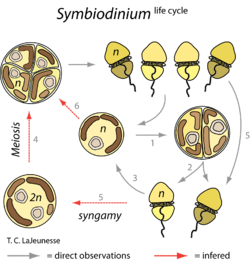

Hello again! This week we will be talking about the life cycles of our new favorite algae friend, Symbiodinium. Last week we talked about how this organism starts its life as a motile mastigote and then settles in a suitable host, most commonly a coral, and loses its flagella to become a stationary cell. Through my research, I am learning that there is not a ton of information of how Symbiodinium actually reproduces. Some sources say it’s sexual and there is some recent evidence to support asexual mitosis (Liu, et al, 2018). There are others who claim there is mostly asexual reproduction with only some evidence of sexual recombination (Porto, et al, 2008). I believe the general consensus is that they can probably do both means of reproduction depending on the conditions.

https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/File:SymbiodiniumLifeCycle.png

(On a side note, I have found the research of this microbe very frustration because there is a ton that is unknown about them. It seems like people only started caring about corals and the organisms that keep them alive when all the reefs started dying.)

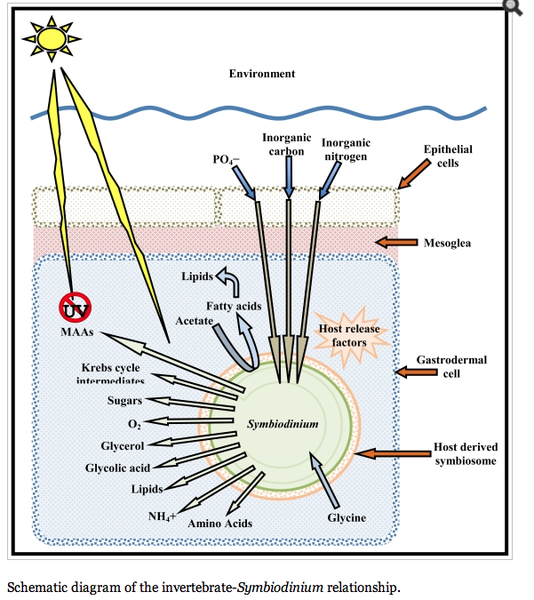

The host is an essential part of this process because it is when they begin this symbiotic relationship with a mollusk or cnidarian where they can begin photosynthesis. The coccoid cells of the Symbiodinium can be found in the gastrodermal cells of coral polyps (Zooxanthellae and their Symbiotic Relationship with Marine Corals., n.d.). Please watch this short video that shows a coral polyp under a confocal microscope. You can see the Symbiodinium in red and really understand where the algae allocate on its host and it’s actually a beautiful clip.

Symbiodinium has a very interesting relationship with its host in that it uses the byproducts of the cellular respiration which are carbon dioxide and water to perform photosynthesis. These algae will then use the suns energy and the coral’s carbon source to photosynthesize and produce carbohydrates and oxygen which the coral can then put back into cellular respiration (NOAA, 2017).

https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/File:Screen_Shot_2014-04-19_at_2.07.20_PM.png

Pretty cool how these critters rely on one another! Next week we will be talking about how essential Symbiodinium actually is to the survival of coral reefs and what the term “coral bleaching” refers to.

Until next time,

-L

Liu, H., Stephens, T. G., González-Pech, R. A., Beltran, V. H., Lapeyre, B., Bongaerts, P., . . . Chan, C. X. (2018, July 17). Symbiodinium genomes reveal adaptive evolution of functions related to coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-018-0098-3

NOAA Ocean Service Education. (2017, July 6). Retrieved March 19, 2019, from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/media/supp_coral02bc.html

Porto, I., Granados, C., Restrepo, J. C., & Sánchez, J. A. (2008, May 14). Macroalgal-Associated Dinoflagellates Belonging to the Genus Symbiodinium in Caribbean Reefs. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0002160

Zooxanthellae and their Symbiotic Relationship with Marine Corals. (n.d.). Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/media/supp_coral02bc.html