Engaging Students in STEM Writing Courses

By Hongmei Zhang, Ph.D. (Department of Biology)

One of the major challenges in the writing-intensive course is the lack of student engagement and motivation. I have struggled a lot to get students engaged in one of the writing courses I teach: Molecular Cell Biology Laboratory-Critical Thinking through Writing (BIOL3810-CTW). The 50-minute CTW component aims to assist STEM major undergraduate students in writing scientific reports. I have paid close attention to the challenges students have encountered and developed a variety of active learning activities accordingly with years-long effort. Here are a few examples:

“Post-It” Activity: Demystifying the Rubrics

Many students do not know what exactly to write even the “rubrics” is provided, so instead of just explaining the rubrics, I asked students to practice through the following activity.

Step 1. Four students as a group discuss and write several complete sentences (e.g., 5 sentences) for a specific writing assignment (e.g., the Introduction of the Enzyme Kinetics) within a certain amount of time (e.g., 15 minutes). Sentences are written on Post-its (one sentence per Post-it), and different groups have Post-its with different colors.

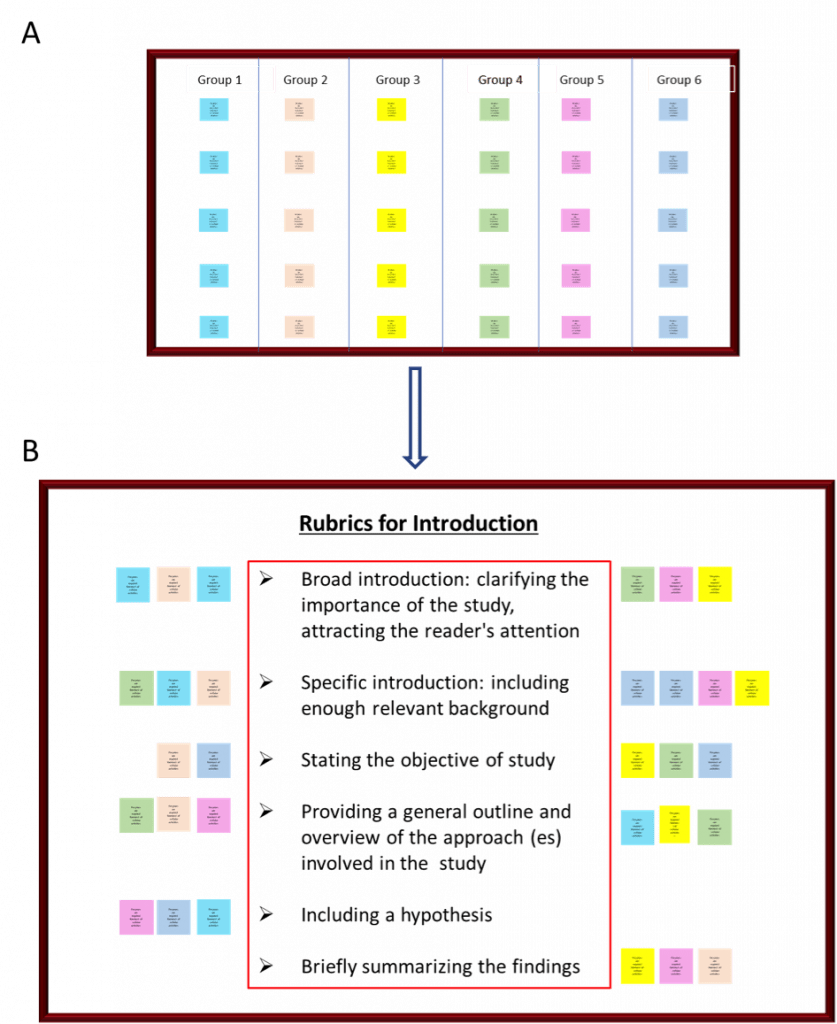

Step 2. Each group puts all Post-its with sentences up on the classroom whiteboard (each group has a column on the board as shown in Fig. 1A), and all students go to the front of the classroom instead of sitting in the back to go through these sentences.

Step 3. The instructor randomly chooses one group to read what they have written.

The entire class analyzes each sentence and determines where the sentence belongs in the Introduction (according to rubrics) under the instructor’s guidance (Fig. 1B). Sentences from more groups are analyzed in the same way, depending on the availability of class time. At the end of the activity, an overall structure or a draft of the Introduction can be visualized.

Figure 1. “Post-it” sentences on the whiteboard. Students in each group put their “Post-it” sentences in their assigned columns on the whiteboard (A). “Post-it” sentences from different groups are analyzed and placed in order according to rubrics (B). For example, some sentences belong to “broad introduction”, and some belong to “specific introduction”. Sentences delivering the same information are placed in the same rows on the whiteboard.

“Paper Puzzle” Activity: Promoting the Understanding of the Structure

Students often struggle with what exactly should be written in the Results section when some information has already been displayed in figures and tables. Then, how about the captions of figures and tables? The following activity gives students a clear picture of each part.

Step 1. Example sentences of a specific experimental section (e.g., the Results of Polymerase Chain Reaction experiment) are constructed by the instructor and placed logically in a document.

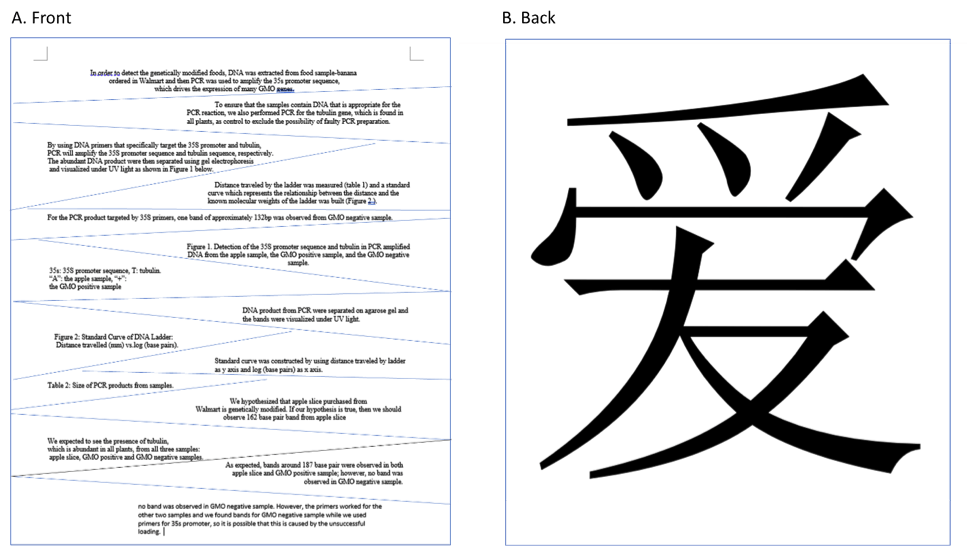

Step 2. The document is printed and cut into different pieces with one sentence on each piece (Fig. 2A, Front). The instructor mixes all pieces together and puts them in one Ziploc bag (one bag for each group).

Step 3. Students, in groups of four, are asked to put different pieces back together just like how they play the puzzle. To complete the task, students need to analyze each sentence and determine the flow of information throughout the entire section.

Step 4. Students receive participation points if they can complete the task; in addition, they have been notified that there is a surprise on the back of the paper if they correctly put the paper puzzle together; for example, Chinese words “Beautiful” or “Love” (Fig. 2B, Back, “Love” in Chinese). At the end of class, an example of the Results can be reconstructed by the students themselves.

Figure 2. The printed document with all sentences in the front (A) and Chinese word (as a special surprise) in the back (B).

“Minute Game” Activity: Enhancing Critical Thinking

In BIOL3810-CTW, writing the Discussion section of the scientific reports particularly requires students’ focus and higher-level critical thinking skills. A “Minute-game” below was designed to facilitate deep discussion.

Step 1. A pair of chopsticks and a small bag of M&M candies are provided for each group. Students are asked to use chopsticks to pick up M&M candies. Whoever picks up the most M&M candies within 10 seconds will be the leader of that group.

Step 2. Students in each group discuss what they should include in the Discussion section of the scientific report for approximately 10 minutes. The group leader is responsible for facilitating brainstorming, recording ideas, and then sharing the group ideas with the rest of the class. Comments from the other groups are always encouraged.

“Musical Chairs” Activity: Improving Technical Writing

The “Musical Chairs” activity was incorporated to provide immediate feedback from their peers as well as the instructor. “Musical Chairs” activity also creates a positive learning environment.

Step1. To maximize the learning efficiency in class, students are asked to complete a homework assignment, which is composed of many sentences, before they come to the class. Students need to either identify and correct errors in the sentences or improve the writing of the sentences to make them more professional.

Step 2. Each sentence is printed on paper by the instructor, wrapped with foil, and mixed in a Ziplock bag so that students can pick one randomly; whoever is eliminated when the music stops will take a sentence out from the Ziplock bag and share how they improved the writing of this sentence in front of the entire class.

Step 3. Other students can also share how they did or give comments on what has been shared. This will be followed by feedback from the instructor. To avoid the possible negative feelings of being eliminated, some surprises (small international souvenirs) instead of sentences can also be wrapped in foil and mixed with sentences. The activity continues until all sentences have been discussed in class (if class time permits).

Highlights of the activities:

1) Providing immediate and quality-guaranteed feedback;

2) Engaging ALL students in class;

3) Being “simple, quick, but critical”.

A student self-survey demonstrated that these activities are very helpful! In addition, with the transition to online learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic, some of these activities (e.g., ‘Post-it’ and “paper puzzle” activities) have been modified and implemented in the online course.

Please feel free to reach out to me at hzhang3@gsu.edu if you have any questions about implementing these activities in your class!