THE BEGINNING OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Public housing began because of the ambitions of Charles F. Palmer, an Atlanta real estate developer, and Dr. John Hope. Charles moved to Atlanta for the opportunity to grow his business and make money in real estate. Once in Atlanta he noticed the slum-like conditions and wanted to help low-income residents.[1] Palmer met and began working alongside Dr. John Hope, a leading African American educator, and leader in the Civil Rights movement. Palmer and Hope began organizing a plan to rid Atlanta’s slums and ease the stress of the poor. It was in 1933 when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office in the midst of the Great Depression. Roosevelt began passing legislation to help the country get back to work. It was during that time that Palmer made his way to Washington D.C. to speak to Roosevelt about the slum conditions of the Atlanta people. Roosevelt agreed to the funding of two public housing developments. The first being Techwood/ Clark Howell Homes, and the second University Homes. Atlanta began to build various government housing developments throughout the city, including “Grady Homes“ in 1942. Henry Grady Homes would house African Americans, one of four housing developments built at that time. Grady Homes amenities would include a recreational space with an auditorium, rooms for the Boys and Girls club meetings, a nursery school, and a playing field.[3]

Grady Homes Public Housing

Grady Homes was considered one of the top slum areas in Atlanta. Located in the Sweet Auburn neighborhood and the center of African American life, at 100 Bell Street just five blocks from Georgia State University. Grady slum houses were old, poorly built, and badly deteriorating. The wooden slum area almost met its demise in the 1917 “Great Atlanta Fire” but was left unscathed. Though in 1938 that was not the case. Twenty units from Grady Homes was consumed by fire causing $500 worth of damage. Fires in Atlanta did not come as a surprise because of the building materials at that time consisted of wood, which was flammable. Many of the houses had no indoor plumbing, running water or baths. The birth rate was two and one-half times the city’s average, and the death rate was twice the average amongst Atlanta residents. The infant mortality rate was three times the city’s average during a time of increased tuberculosis cases.[4] Grady Homes Housing Development like other public housing developments were built to help low-income families who were unemployed and living below the poverty line during the ails of the Great Depression. Building public housing would not only give working men jobs and a way to provide for their families, but the outcome would rid the city of some of the worst slums in the nation. In 1934, before the development of Grady Homes public housing, there were small businesses located on Bell Street (pencil factories and auto repair shops). By 1942 and just before public housing consumed the area. Bell Street consisted of wooden residential structures, home to Black African Americans during a time “Jim Crow” laws.

Grady Homes public housing was constructed in 1942 for African American families. 616 wooden-slum houses were demolished to build 495 newly barrack style brick homes on 22.8 acres. The apartments were located East of the city and were densely constructed. The new residents fell in love with the neighborhood, as it was viewed as vibrant and friendly. The community offered daycare for working parents, a playground for children and many activities promoted by management to engage the residents. The young residents engaged in activities like the Boys and Girls Clubs, and Youth Football League games (Golden Bears). Working residents had access to child care at the Grady Homes Head Start Daycare facility, where children prepared for grade school. Though by 1984, the daycare was faced with a cut in funding from the government. The community tried to raise the $28,000 needed but came up short. The Economic Opportunity Atlanta closed the Head Start Program of Grady Homes, leaving over a hundred students without childcare.

Additionally, public housing developments all over the city began to become disastrously affected by the lack of funds from the Federal Housing Act, which was created to build housing, but not for the upkeep of the developments. The apartment units suffered from broken windows, lights, doors, and low maintenance on all levels. By the mid-1980’s crack cocaine became a major epidemic and took over almost all public housing causing an increase in criminal behavior. When a gang by the name “Miami Boys” moved into the city, death, robbery, and gun violence increased inside Atlanta’s housing units. The Miami Boys were able to move into neighborhoods around the city including Grady Homes and took over vacant apartments, where they sold drugs.[5] Residents felt unsafe, and while only a small amount could afford to move out, most did not, and the vacant apartments turned into drug camps. In 1992, the Atlanta Police Department logged 276 crimes classified as Type I in the Grady Homes housing development. Just two years later the conviction of two men in the death of a 13-year-old girl was handed down. In this criminal case, a young girl was used as a human shield during an altercation over drugs.[6] (Grady Homes crime)

Despite the increase in crime, “administrative records indicated that by 1994, adults that lived at Grady Homes were more upwardly mobile than the adults that lived at most other public housing developments around the city.”[7] As time progressed, the operations of Atlanta Housing Authority became deliberately corrupt and poorly managed, leading to a Federal audit that scored their performance at 37%. As a result, a new housing director was appointed in 1994, and the Atlanta Housing Authority set their sights on revitalizing public housing, which has become the new modern-day slums of the city.

REVITALIZATION

Revitalization of Grady Homes and other public housing developments came to most as swift, unjust, and a human rights violation. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development created the HOPE VI policy. Named formally as the Urban Revitalization Demonstration Program, created by Congress in 1992. The policy was intended to revamp public housing into new mixed-income housing and forward-thinking, innovative businesses. In 1993, Atlanta’s Housing Authority received a HOPE VI grant to revitalizes two of its twenty-five public housing developments. Atlanta’s public housing, though crime-ridden and dangerous, was a place where residents felt a sense of community, comfort, and a sense of “home.” The discourse between government policy on public housing and its community is one of debate.

Government officials on the national level felt that “public housing is not merely a failure, but an apocalyptic tragedy.”[8] Public Housing became known as a nightmare and a place of poverty that was decaying around the city. Constituting a community of mixed-income housing would improve and alleviate the living standards of the poor modern-day slum residents. The argument that public housing was anachronistic and old-fashion aided in the discourse to revitalize them. “More common, however, was the belief that local housing authorities willfully neglected the properties to receive HOPE VI and justify demolition.”[9]

Antagonistically, the residents that have lived in public housing for decades, and have raised their children there, believed the revitalization was to make way for a more prosperous and more lucrative neighborhood. Public Housing residents “find that close social ties are more common and stronger in public housing than in other forms of assisted housing.”[10] There is a sense of security and strong place attachment within the comfort of public housing. Residents equated public housing to a “village” to which they do not want to leave but have been forced to relocate.

END OF GRADY HOMES

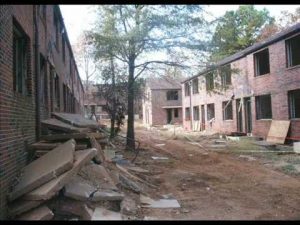

The relocation of residents and demolition of Grady Homes started in 2005. HOPE VI funds were allocated at the beginning of the redevelopment of public housing, however by 2006 President G.W. Bush felt that “the results achieved thus far did not warrant its continuation.”[11] Residents chose between housing vouchers, section 8 vouchers, or relocation to a housing project that would not be demolished. “Atlanta Housing Authority’s (AHA) innovative revitalization program, in partnership with private real estate developers, created sixteen master-planned, mixed-use, mixed-income communities on the sites of former public housing projects.”[12] Grady Homes turned into Ashley Auburn Pointe, a mixed-income community with 304 apartment units. Atlanta made history once again, not only was they first to build government housing for low income impoverished people, but they were also the first to rid the city of its’ developments.