“Student Innovation Fellows: INNOVATE !”

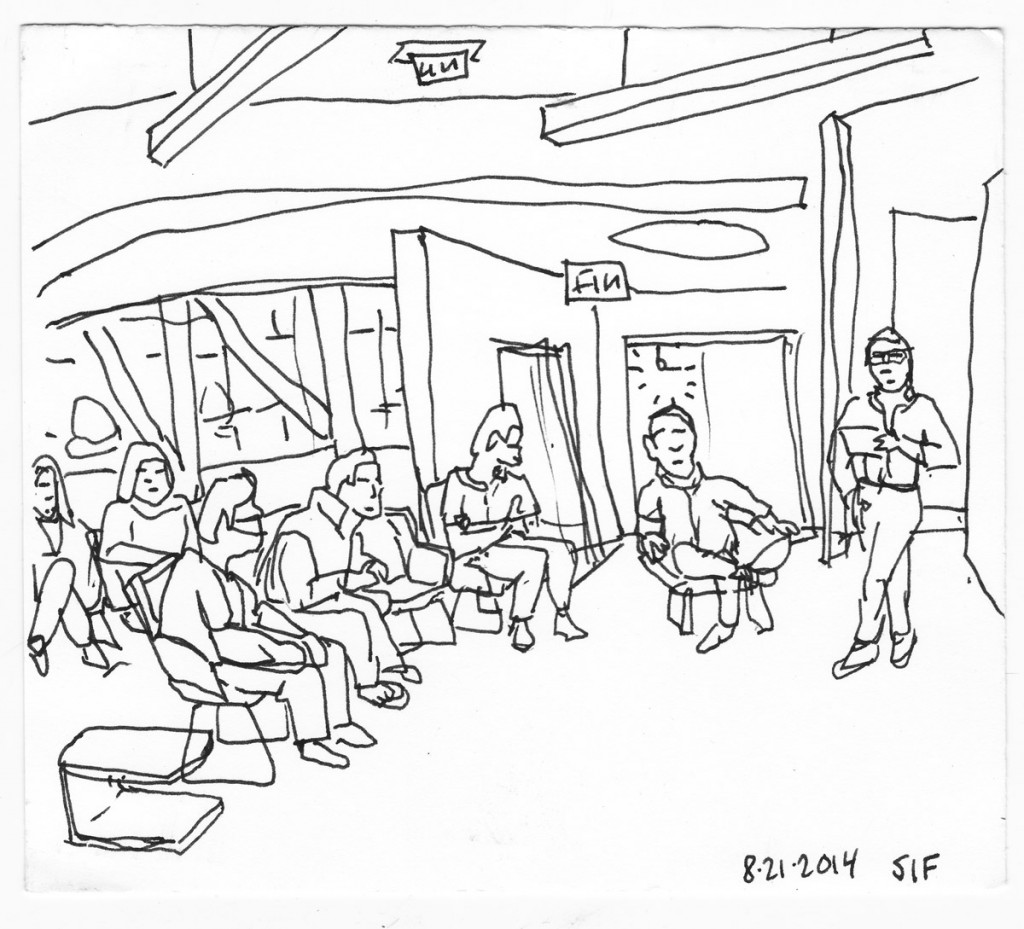

All the Student Innovation Fellows gathered for an initial meeting last Thursday. It was wonderful to see the breadth and energy of the group, with SIFs from GSU undergraduate and graduate programs across a range of disciplines. We are all looking forward to the exciting prospects that the SIF program opens up, for us and for the GSU community.

The i has it.

The reader of an ebook faces the question: which reader software should I use? The creator of an ebook faces the question: which ebook format should I use? In neither case is there a universally “best” answer.

As business interests have scrambled to try to capture the ebook market, many formats have been introduced. This completely unregulated environment has created a certain amount of confusion and a lack of uniformity.

Ebook (or ebook or eBook) formats fall into some broad categories. First, those based strictly on their internal structure:

- epub (or ePub)

- text (or txt)

Next, ebook formats based both on internal structure and the means to read them:

- iBooks (read exclusively on iOS devices)

- MOBI (Third party readers such as Stanza, FBReader, Kindle for PC and Mac, and STDU Viewer can open MOBI files.)

- AZW (used exclusively on the Amazon Kindle)

It is important to note that these categories are not mutually exclusive. That is, while one must use ibook reader to read an ibook, one can also use ibook reader to read epubs, pdf, and text files (but not MOBI or AZW formats). In general, the formats based strictly on internal structure are the most adaptable to the widest range of reader software. However, it is also true that ebook formats based on internal structure and the means to read them offer more bells and whistles: design options, interactivity, multimedia, etc.

(There are myriad other ebook formats; I list above only the most popular.)

Amazon, as the big player in the online shopping world, seeks to force its format on the world. Thus, if one buys an ebook on Amazon, it will be in a format readily on Amazon’s product: the Kindle.

Similarly, Apple (as the big player in the tablet market), seeks to force its format on the world. So, buying a book through the Apple store means buying a book in iBook format, readable on Apple’s reader product, which runs only on Apple devices.

All of these is rather unsatisfying. It is as if Apple (or Amazon) decided only to release its books in the French language. If you can’t read French, then get French lessons! Oh, and Apple is the only French teacher in town.

In some respects, the iBook format stands apart.

Consider as evidence of this the fact that, these recent articles surveying ebook formats (via Google search) don’t even mention ibooks: 1, 2, 3, 4. This kind of general inquiry into the web reveals that the general internet population has resisted viewing ibooks as a significant ebook format. At most universities, Windows-based machines still dominate, and certainly Windows is the overwhelming platform for the less advantaged parts of the world. Further, ibooks (unlike epub, pdf, txt, etc.) isn’t a format that one can read online, cutting off another large chunk of the population. On the other hand, iBooks has created a format which offers the widest range of design features, making it attractive to book designers who want to create a book with style, multimedia, and other advanced features. Authors simply have to decide whether or not these features are worth the enormous shutting out of possible readers that goes along with the iBooks format.

Finally, it is important not to demonize Apple too harshly: Amazon had already initiated its attempt to corner the market, and Apple’s response was largely “business as usual.”

A somewhat onerous option that many choose is to create their book in multiple formats: a design-rich format for iBooks, and a widely useable epub format for other devices: this is the approach we are working toward for our Tobacco Study book, the goal being to produce an innovate ebook (through ibooks author) and a widely useable one (a reflowable version).

Innovating an Ancient Innovation

My first SIF project predates my appointment as a Student Innovation Fellow by several weeks. Now that’s innovative!

I was brought onto a project of the School of Public Health to generate an ebook based on the School’s research into the effects of Tobacco use on public health. My own exposure to this project predates even further: I attended a talk at the College of Law (where I am student) last year, shortly after the School of Public Health received a $19 million grant to pursue this research, the largest grant in GSU history. My interest in public health fits within my general interest in public interest legal work. It is a great honor for me to be a part of this project.

Initially, I began a broad inquiry into ebooks, truly untamed jungle of formats, features, and (in)compatibilities. An ebook is perforce defined by its method of reading. Thus, speaking most broadly, if a text is read on an electronic device, it is an ebook.

Marie Lebert of the University of Toronto wrote a “Short History of eBooks” in 2009, “based on 100 interviews conducted worldwide and thousands of hours of web surfing during ten years.” It begins with Project Gutenberg, the first digital library of texts, initiated in 1917: long before “e” meant “electronic”. The Government Printing Office offers a (much shorter) article focused on the state of things at present: “The History of eBooks from 1930’s “Readies” to Today’s GPO eBook Services.”

Marie Lebert of the University of Toronto wrote a “Short History of eBooks” in 2009, “based on 100 interviews conducted worldwide and thousands of hours of web surfing during ten years.” It begins with Project Gutenberg, the first digital library of texts, initiated in 1917: long before “e” meant “electronic”. The Government Printing Office offers a (much shorter) article focused on the state of things at present: “The History of eBooks from 1930’s “Readies” to Today’s GPO eBook Services.”

A familiar comparison is: the ebook vs. the book. This contrast is premised mainly on the long and rich history of books. Any new form of the book must measure itself against that, just as any innovative technology will be judged not merely on the “new” in innovation, but also on its superior qualities with respect to the old. Another way to put this: if a purported innovation isn’t better than what already exists, then in what sense is it an innovation?

The famous essay by Isaac Asimov, “The Ancient and the Ultimate” (1973) lays out this challenge quite effectively. (The link is to an essay about the essay… you can find Asimov’s essay in several of his collections, including “Asimov on Science” and also here on JSTOR.) Asimov’s clever inquiry isn’t designed to question technology, but mainly to illuminate just how technologically perfect a book is.

Seemingly the promised ebook revolution (throw away those bulky, dusty, paper-cut-inducing books and get whizbang-modern!) arrived when… sellable products arrived. I.e., the revolution will be marketed to you. The ubiquity of ebooks owes everything to Amazon (who makes Kindle) and Apple (who makes the iPad). Even though electronic book formats have existed for as long as the internet, suddenly the “We Have EBooks” moment had arrived. This is, I suppose, little different than the original print revolution. Books had been around for centuries, but it was only when the technology for delivery appeared in the form of the printing press that the book became a power in itself.

The product-based nature of the current ebook revolution makes a cynical person wonder that the original revolution of printing, which freed ideas from the exclusive control of a few, creating to opportunity for an explosion in learning and information transmission, isn’t being co-opted by the media controllers? Is knowledge freed, or merely the purse strings of the masses?

The truth is, myriad ebook formats are free and the tools for their creation open source. And too, many writers and activists fight for more open copyright standards and more free means of distributing texts.

The desire to make an ebook with the widest possible distribution figured significantly into my work on the School of Public Health ebook… more on that in the next entry.