Who is buying ebooks? And who is reading them?

By some metrics, the ebook wave has crested.

While they have not yet been around long enough to merit a Gibbon-esque Rise and Fall, some web authors offer only moderately partisan summaries of the state of the book, claiming that ebook sales and readership have reached their peak, and that the trend indicates that there will always be more traditional books than ebooks.Of course, statistics, like voting districts, are most often cultivated ways to describe a result, rather than a raw measure of factual information.

First, some general comments on the reasons behind a general flattening in e-book sales. First, ebook prices have risen, perhaps driving readers back to used print copies or libraries. As the writer of that article (on the site called dear author.com) notes, the reduced price of ebooks ought to follow not only from lower overhead costs, but also due to the limited set of rights one acquires when purchings an ebook: “If a publisher wants me to pay a price nearly commensurate with a hardcover copy from Target or other big box chain, I expect the same rights to come with the digital copy, including, the right to lend or borrow, the right to re-sell, and the right to own my copy outright without limitations like DRM.”

The comments (118 — the article was posted on 10 March) to the above-linked article reveal that perhaps the reading public has settled on a fair price for an ebook — six or seven dollars — and that many readers refuse to budge. For ebook sellers, this presents a problem: elevate prices and lose sales, thus perhaps stalling the industry, or accept the what the market will bear and become stuck on a pricing structure difficult to move, even with “special features.”

Dan Cohen (“Executive Director of the Digital Public Library of America”) in “What’s the matter with Ebooks?” writes that after an initial surge on the release of the Kindle and iPad, “ebook adoption has plateaued at about a third of the overall book market, and this stall has lasted for over a year now.”

New statistics from Nielsen Books & Consumer show that ebooks were outsold by both hardcovers AND paperbacks in the first half of 2014.

According to the survey, ebook sales made up 23% of unit sales for the first six months of this year, while hardcover’s accounted for 25% and paperbacks 42% of sales. [link]

Cohen frames these findings in light of the fact that such surveys are usually comparing books “from major publishers in relation to the sales of print books from those same publishers“. Expanding the field to include medium, small, indie, and self-publishers changes things a bit. One must consider books that are only published in one format or the other. It is obvious that the ease of publishing an ebook is going to lead to more and more of them appearing.

Gauges of ebook sales must, I think, cut out some of the chafe. A market is always market-driven, and thus the big fish are going to weigh more heavily in the scales that determine whether ebooks are surpassing traditional books in the marketplace. On the other hand, as the small fish multiply, the big publishers will have to take note of the fact that people are choosing to read on electronic devices (if only because the small fish don’t swim in the print pool… as ’twere).

One could imagine a market trend similar to the one that is transforming entertainment and news: web-based content, produced far from the highly developed production world of television and cable, has forced that advertisers to rethink how they disperse their money. Similarly, social media transformed the way people consume every kind of web-based content, effecting a similar change in economic perspective.

Examining a population that is both presumed to favor electronic devices, and also one that might presage future trends, a Publishing Technology survey of “1,000 consumers across the U.S., aged between 18 and 34”

found that in the last year, nearly twice as many respondents had read a print book (79 percent), than an ebook on any device – the closest being a tablet (46 percent).

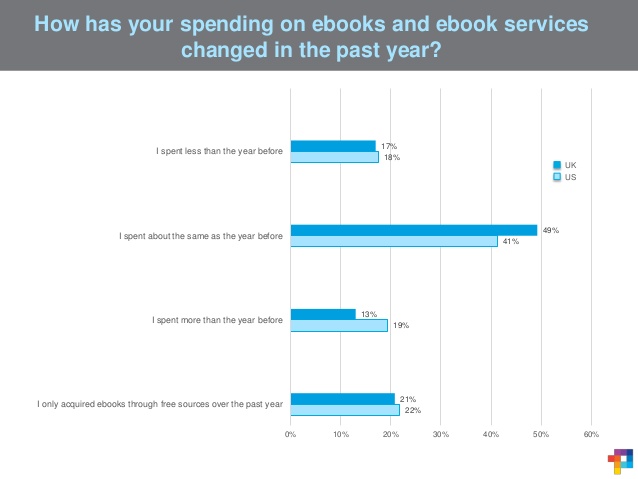

One question seems to corroborate the general flattening out of the ebook market:

Analysis of the survey reveals some of the psychological roots in resistance to ebooks:

This rising cohort of book-buyers relies on peers for suggestions of what to read, often prefers cheaper, smaller bites that can be shared freely, and revels in the luxury of being able to read whenever and wherever it likes – regardless of format or platform.

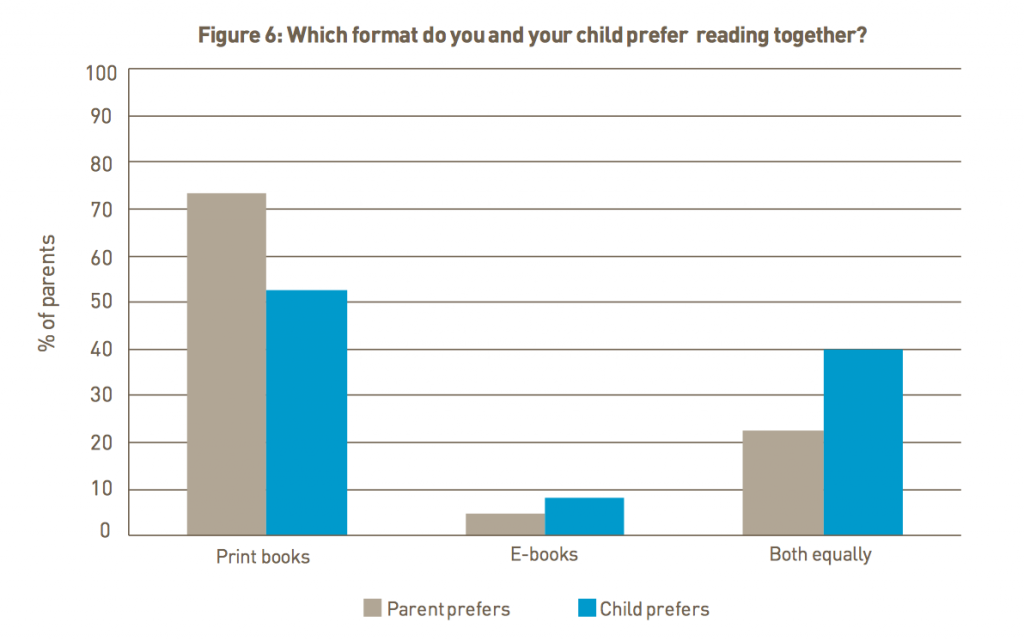

Another psychological (or motivation) limit thus far on runaway ebook sales is a 2012 study showing, among other things, the reasons why some parents do not co-read e-books with their children (mean age of child, around four years old):

The same study reveals that, generally, parents (and children) don’t prefer co-reading ebooks: