At a Glance: The Contested Identity of Auburn

City planners have always been recognized for creating cities that are livable, beautiful, and inclusive. Almost anyone who knows about Atlanta knows about the skyline, the instrastructure, and of course, the traffic, but most people don’t look close enough to see the history and implications of the environment. City planners and creators of the built environment do more than just create a physical space that evokes these characteristics. Through decisions concerning the remodeling or preservation of certain elements in a given space, city planners have the power to likewise remodel or preserve the memory of a place, event, person, or even an entire movement. I intend to explain the many ways that the city influences memories of landscape by explaining the current dilemma of Auburn Avenue, the landmarks of the street, the mixture of historic and current buildings and businesses, and the hidden truths implicit in the landscape.

Fighting to Keep History

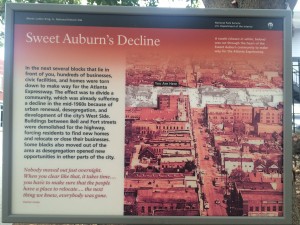

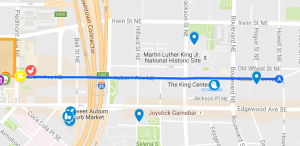

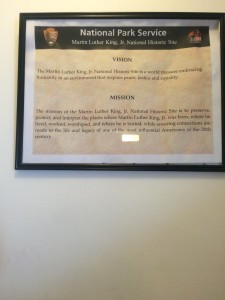

One largely fought over piece of Atlanta is historic Auburn Avenue. The street has been credited as the birth home of the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta, Georgia. It is the home and grave of Martin Luther King Jr. and his family’s church, Ebenezer Baptist. Some people believe this street should stay true to its historic roots and that the buildings should be maintained to reflect their past glory and to honor the movement. However, the street has been in a spiraling decline since the white flight of the area with the introduction of highway infrastructure. Therefore, there is a push to modernize the street to make it economically viable. Both sides of the argument admit the role the street has played in the city and both present pressing evidence for their claims. However, what both sides fail to understand is the role the city has played in the creating of the street. The city planners of Atlanta have crafted Auburn Avenue to highlight its role in the civil rights movement as well as its more appealing functions, but neglects to tell the entire story. By emphasizing the past, the present is forgotten as well.

The Function of Landmarks

Landscapes and the built environment have many functions. They are practical in that they are created to be used, experienced, and inhabited. However, they also have imbedded memories and histories, and the way an environment is built is an intentional practice. It does not just happen. Just like history textbooks, the way the world is constructed is not entirely truthful. There is always a bias. The environment is constructed based on how the geographers and city planners choose to write history. The way we imagine ourselves is linked to how we remember ourselves and our identity. There are many debates about what and who should be remembered and forgotten. However, opinions about these things change over time and are ultimately battled for in the landscape “arena.” The landscape is important to public memory because it is affected by the memory as much as it creates the memory. For this reason, the landscape of the built environment must be more thoroughly examined for the truth, as many landscapes do not acknowledge all points of the past are represented. This call for investigation applies directly to my research on Auburn Avenue and the King District.

Remembered and Forgotten Auburn Avenue

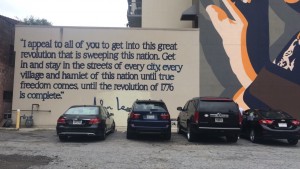

The Historic Site and surrounding area produce a story of the civil rights movement that glamorizes the integration of history but ignores continued legacies of racism. In making the site, Atlanta provides a story of positive social change to market a progressive southern city. It also presents an interesting example of the street naming system that supposedly commemorates historic leaders, but also symbolically keeps racial groups separate and labeled. The renaming of streets and other areas of cities after Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders in the Civil Rights Movement is done purposefully. There is a trouble faced by the African American population that is primarily responsible for the street renaming in these instances and it is done as a way to create a new geography of memory in a white dominated cultural landscape. Certain problems include the politics of place-naming as a way to inscribe exactly what is wanted as far as ideology and values, politics of constructing a cohesive history through commemoration, and the issue of spreading the message outside of only certain “black” areas. There is a call for violent pasts to be commemorated so that the full truth may be exposed. This will be a part of the peace and reconciliation process.

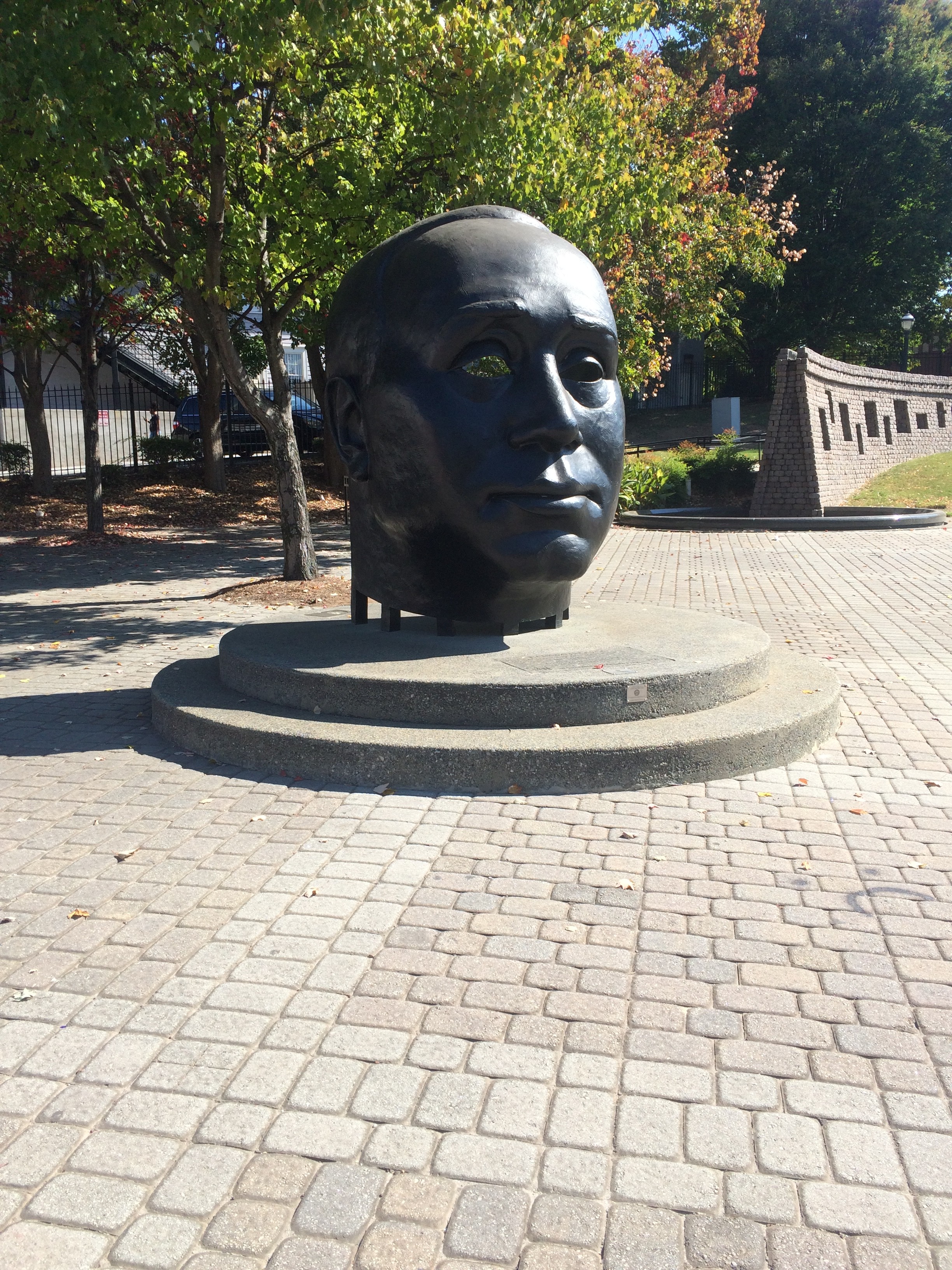

Auburn Avenue, specifically the King District, has worked to shape Atlanta’s characterization and the way it is remembered. Specifically, “the memorials along Auburn Avenue are powerful sites to interrogate the intersections of race, nation and the cultural landscape as they encourage us to remember certain aspects of US history and to forget others; the monuments dedicated to Dr. King become ‘selective aids to memory’ and are related to the production of hegemony.” Memory is expressed through memorials such as King’s in a certain way that communicates specific economic, cultural, and political ideas. King’s site is utilized to emphasize aspects of non-violence and unity, while ignoring more radical aspects of the movement.

Delving into Auburn Avenue

“The study of landscape should move beyond mere surface readings and delve instead into the gritty, often ugly, sometimes energizing social history of specific places.” Marginalized groups can take advantage of the geography of landscapes that shaped their history to make statements and give them a voice. Sometimes the built environment is misused, but it can be changed and utilized to effectively portray the true history.

There is a counter-public nature to Auburn Avenue. It was once a social hub for the black community to get together and organize change when they could not interact in the usual public spheres. Auburn Avenue was one of the most influential counter-publics for the civil rights movement, but Auburn Avenue is far from its hay-day. There are many opinions about what can and should be done with the remains of such a prosperous and historic street. The development project for Auburn Avenue, Big Bethel, is emblematic of contemporary black counter-public spaces and links its identity to African American identity. Because the street has not only been recognized in the past as a black neighborhood, but also as a richer black neighborhood, there is also intersectionality of race and class and the two groups affect one another.

The issues that Auburn Avenue faces are not black and white. They are not merely a racial issue of what African Americans want versus what white Americans want, but are rather issues of what various groups of people want regardless of race. There are conflicting interest groups within the Auburn Avenue community that are adamant about their stances on what should happen to the street in the future.

Sources:

Atlanta’s historic Auburn Ave. again at crossroads | Fox News

CONSTRUCTING AFRICAN AMERICAN URBAN SPACE IN ATLANTA, GEORGIA

Contested Memory in the Birthplace of a King

Forum on Social Justice in the South: Introduction

Creating a New Geography of Memory