Growing up, I was a little boy who was in love with the sport of baseball. Wherever I went, I had a ball and glove close by me. If somebody had a question about who was leading the league in home runs, or who won the World Series in the most random year, there was a high chance I knew. This love was sparked by a Major League Baseball team that resided just an hour south of where I grew up: the Atlanta Braves. Being an hour away, my family did not travel down to see them play live much when I was growing up, but I did watch every game on television. Every time we made it down, I enjoyed every minute of it. I still vaguely remember my first game at Turner Field. I got to watch and learn from the players who became my heroes. When I began to get older, I started going to at least five games a year. Through all the times that I showed up, the thought never popped into my head that there was something that resided in this spot before the stadium did. But the area where Turner Field currently stands and Atlanta-Fulton County stadium had once stood, was the area that several individuals lived and worked. My mission here is to carry you on the journey from the early settlements to the events that brought us to the Turner Field area as it is known today.

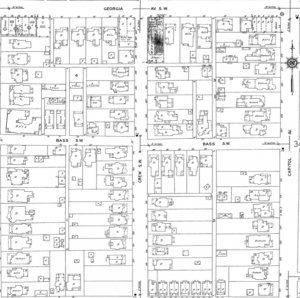

Area where Fulton County Stadium once stood. Atlanta 1931-1932, sheet 336, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Journeying back to pre-World War II times, the present day Turner Field complex was an 8 block residential area that was surrounded by three communities: “Summerhill to the north and east, Mechanicsville to the west, and Peoplestown to the south.” These communities had consisted of descendants of freed slaves as well as Jewish immigrants.[1] The freed slaves that moved to Atlanta, began building in south Atlanta. The settlement was first known as Baileyville. Later, it was renamed to Summerhill due to the bright hopes of the citizens, as well as, the hills that to roll through the landscape.[2] In 1932, the area was home to many local businesses and buildings such as: Paragon Pharmacy, Empire Theater, Superfine Ice Cream Company, and many more small service business and housing complexes and apartments. One small business stuck out to me and it was located at 29 Georgia Avenue SW and Capitol Avenue intersection. It was a miniature golf course. [3]Not something one would necessarily expect from the early 1930’s. But nonetheless, the residents of these areas were in well functioning community. They held many local events and clubs that residents could be apart of and join. This community had everything that you could begin to ask for, in order for it to succeed.

Area where Turner Field currently stands. Atlanta 1931-1932, sheet 342, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

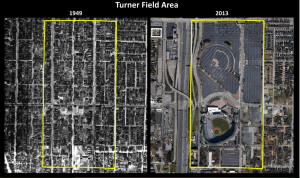

After World War II, the area began to change. Industries began to leave the city and not long after the residents did as well. The Jewish community moved north to the Druid Hills area, and blacks moved west to the Cascade area. What was left was a part of the poor and working class. This led to a slow deterioration of the communities. The area became an area of mostly poor African American families. Then, in June of 1946, Atlanta City council began to seek funds for a north south expressway that would run through Atlanta. The city asked for a 20.4-million-dollar bond that would be taking out of the 40.4-million-dollar bond that was given to the city for improvements.[4] This expressways purpose was to easily bring in individuals from suburban areas for jobs by running this north south expressway just east of the central business district. But in doing so, they would be displacing many residents of the community. Larry Keating wrote that an unstated goal of this expressway was “to remove as many poor blacks from the downtown area as possible.[5] The construction of the expressway “created rigid barriers between once-close communities” and completely changed the look of the area.

Map of Turner Field Area 1949 and 2013. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Hurley, Georgia State University Library Blog.)

The expressway relocated 3,800 residents, and when the local residents became fewer, local business shut down. Leaving the area to begin to decay as if life had stopped there all together.[6]

Moving to the 1960’s, the area had become a slum. But with the condition that the area was in, it made it easier for the city to choose this portion of the Summerhill area for there next project. Mayor Ivan Allen had been wanting to build a stadium in the city of Atlanta since before he was elected mayor of the city.[7] He wanted it to bring money for the city, as well as, to try and attract a Major League Baseball team. This was not so welcomed form the residents of the area. They wanted to see low-income housing built for the community. As Larry Keating wrote in his book, Atlanta, to the residents of Summerhill and Peoplestown, “Allen’s actions seemed like betrayal, for they had been promised that their neighborhoods would be redeveloped. But Allen was set on getting his stadium. So on March 6, 1964 the city held a hearing for the stadium in order to determine the location, how much the state was going to help, and the final cost of the project.[8] In April of 1964, they broke ground on the stadium. It took less than a year for the stadium to be completed.

“Exterior construction of the Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, 1965.” (Photo courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.)

Then in 1966, the Milwaukee Braves signed a contract that moved them to Atlanta in 1966 where they have been up to present time. Atlanta gained prestige and a new source of entertainment with the Braves but for the city “it contributed very little to the downtown economy.” The statistics go on to support that “the stadium actually diminished downtown commercial activity.” [9]

The early 1990’s brought news of another huge event, as well as, another huge transformation scheduled for the area. In 1990, Atlanta won the bid for the 1996 Summer Olympics. With that, Atlanta spent the first 5 years preparing. But the city wanted to make a statement by building a complex that would host a variety events. This complex was an 85,000-seat stadium that would be just south of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. As one would think, residents of the area were not for this decision at all. The residents were upset because Atlanta already had a stadium. “There should be only one stadium before and after the Olympics,” said Vincent Forte, who was a community spokesman.[10] Demonstrators against the stadium, tried to protest the Olympic Stadium groundbreaking, but to no avail. The building of the Olympic Stadium began in July of 1993 and ended two years later in the summer of 1995.[11]

Aerial view of proposed site for Olympic Stadium, 1992. (Photo courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.)

After losing the battle to stop the stadium being built, the residents of Summerhill changed their opinion on the stadium in order to push to gain benefits from it. They wanted to be the “primary stadium-area neighborhood,” in order to receive funding to the redevelopment. The accomplished this by securing both the area of Fulton-County Stadium, as well as, the area of the Olympic Stadium. Unfortunately, the promises of the city were not strong enough in their outcome. The community of Summerhill continued to further degrade. [12]

Olympic Stadium on left being remodel after the Olympic Games and Atlanta-Fulton County stadium on right. Sept. 5, 1996 (Photo Courtesy of AJC Staff Joe McTyre.)

After the Olympics, the Olympic Stadium was remodeled for the Atlanta Braves. The 85,000 –seat stadium was transformed into a just under 50,000-seat stadium while Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was demolished and turned into parking. In 1997, the Braves played their first season inside the park. Olympic Stadium was then renamed Turner Field after then owner, Ted Turner. The Braves have continued to be residents of the stadium for the last 18 years. But on “November 2013, the Atlanta Braves announced plans to relocate to Cobb County, building a new stadium and leaving Turner Field after their lease expires in 2016.”[13] With the decision of the Braves leaving, the City of Atlanta began pondering on what would replace Turner Field. They received many offers from companies such as: residential and commercial development, and also an offer by Georgia State University. Georgia State looks to demolish Turner Field and transform the area into a “mix of student housing, stadiums, and retail.” The community surrounding this area want a development that will benefit the community. Local resident David Holder stated, ‘“We don’t want to necessarily be Midtown or Old Fourth War, but we want something to walk to on the weekend. We want to spend our money in our communities and watch it prosper.”’[14]

So now, what the future holds for the Summerhill community is up for grabs. Being a resident of the community for the past two years, I can say there have been improvements to the area. But the next question is, what is going to be done in the wake of The Braves leaving town? If there is one thing that is for sure, it is that this community not only wants to thrive but it deserves it. It has been through neglect from the city since the early 1900’s, but now it is time for it to begin to prosper like the settlers intended for it.

[1] Burns, Rebecca. “The Other 284 Days – Atlanta Magazine.” Atlanta Magazine. June 21, 2013. Accessed November 5, 2015. http://www.atlantamagazine.com/great-reads/turner-field-development/.

[2] SKIP MASON, Contributing Editor. 2001. “Three Atlanta Neighborhoods: Summerhill, Washington Park, Vine City.” Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), May 27

[3] “Householders and Occupants of Office Buildings and Other Business Places.” Atlanta City Directory. Atlanta: Atlanta City Directory Company, 1932. 1302-1303.

[4]“Council Will Seek Survey Funds for North-South City Expressway.” 1946.The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Jun 13, 1946.

[5] Keating, Larry. “Redevelopment, Atlanta Style.” In Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion, 91. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 2001.

[6] Burns, Rebecca. “The Other 284 Days – Atlanta Magazine.”

[7] Jesse OUTLAR, Sports Editor. 1963. “Stadium Wanted?” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Feb 02

[8] Thompson, Wayne. 1964. “Stadium Hearing at City Hall Today.” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Mar 06

[9] Keating, 102

[10] Roughton Jr., Bert. “Panel: Raze Stadium, Use Site for New One; But Still Prefers ’96 Facility Go Elsewhere.” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, August 9, 1991, Local News: Section F sec.

[11] “Demonstrators have Little Effect on Olympic Stadium Groundbreaking.” 1993.Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), Jul 15

[12] Keating, 174

[13] Burns, Rebecca. “The Other 284 Days – Atlanta Magazine.”

[14] Lee, Maggie, and Thomas Wheatley. “The Bids Are In: The Contest to Redevelop Turner Field Appears to Be Georgia State’s to Lose.” Creative Loafing, December 3, 2015, Cover sec.