This building, which is the result of a sequence of viaduct constructions that began in 1899, lies on top of what is currently known as “Underground Atlanta”.[1] A viaduct project commenced in response to the growing traffic problem. The automobile’s growing popularity clashed with the preexisting railroads. The rise in the automobile’s popularity contributed to significant increases in traffic congestion as well as accidents on the city’s roadways.

VIADUCTS

In 1928, the last viaduct construction commenced, thereby completing the puzzle for the area. The Alabama Street-Pryor Street-Central Avenue viaduct system stood 776 feet above the original ground level.[2] The completion of the viaducts in these areas made travel safer for pedestrians and streetcars.

View of Alabama Street (now Lower and Upper Alabama Streets) looking towards the Georgia Railroad Freight Depot during construction of the viaduct that would support Upper Alabama Street in downtown Atlanta, Georgia.

The viaducts allowed streetcars to travel with much more ease. “…Before the Central Avenue and Pryor Street viaducts were completed in 1929, streetcars making north-south crosstown trips had to cross the railroad tracks—which bisected the downtown area—by means of three bridges: one at Whitehall Street, another at Broad Street, and a third at Forsyth Street.”[3] The viaducts also ensured safer travel for the automobile, which began to gain popularity around this time.

UNDERGROUND ATLANTA

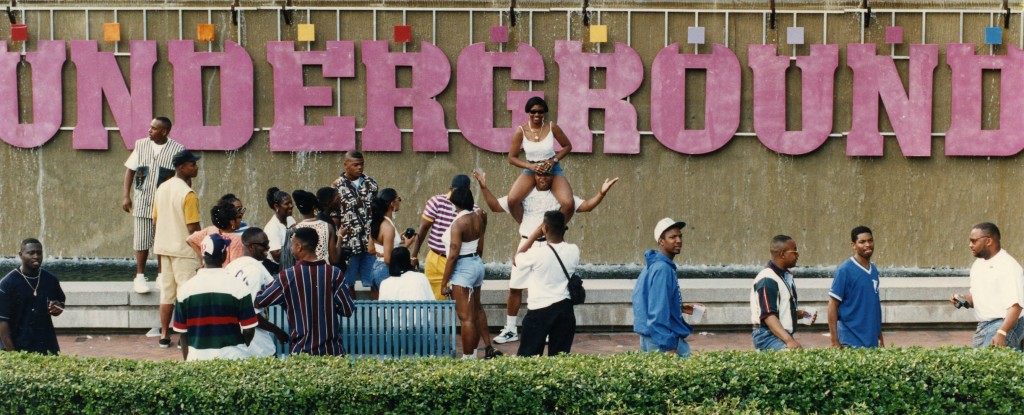

Marlene Karas, “African American college students posing outside of Underground Atlanta during Freaknik, Atlanta, Georgia, April 23, 1994.” AJCP196-050a, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The name Underground Atlanta is a rather misleading term since this area is the original ground level of the city. Workers completed the viaducts in 1929, but the area remained largely vacant and unaccounted for. In 1969, the goal of creating city nightlife spurred the completion of a development that transformed the area. The nightlife scene was booming with bars and clubs but soon plummeted in 1981, shortly after its opening.[4] In 1989, the government used city efforts, including $85 million in bonds, to revitalize Underground. Despite the efforts to refresh the Underground scene, presence fell short and left many businesses failing.[5]

BACKGROUND

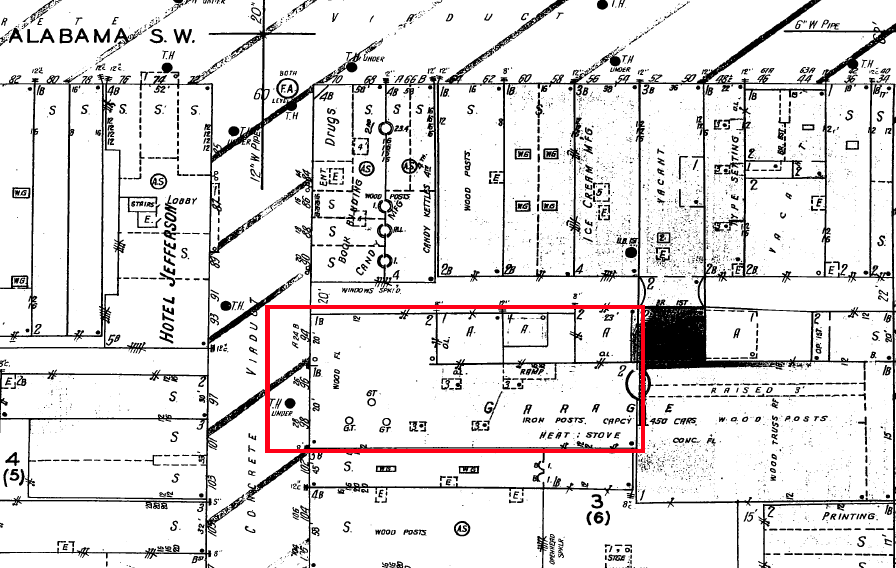

Pryor Street, Atlanta 1931-1932, sheet 16, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

94 Pryor is located in red box.

Located on 94 Pryor Street, this building has a long history of automobile-related businesses. Shortly after the completion of the viaduct construction in 1929, the building remained vacant.[6] Bell Bros Garage became the occupier beginning in 1930. The business remained the occupier up until 1935. B Franklin Bell was listed as the business owner during this time.[7] From 1936 to 1937, Gilbert Storage Garage occupied the building for two short years. A man named Milton T. Gilbert operated the building.[8] Following this two-year period, Mason-Kominers Tire Co. converted the place into a storage space and utilized it from 1938-1939.[9] Claude C. Mason Jr. and Seymour K. Kominers owned the business.[10] Robinson and Stephens Garage Auto Repair became the new occupants in 1940 and remained the occupants until 1955.[11] In 1956, Central Parking Inc. was formed and remained tenants until 1964 when Allright Auto Parks bought out Central Parking.[12]

LOMBARDI’S

It is unclear when exactly this long history of garages transformed into an outlet for hospitality. In 1989, Alberto Lombardi made his way from Dallas, Texas to Atlanta. This was his first venture to expand the Lombardi name outside of Texas. [13]

“Alberto Lombardi in his Highland Park Village restaurant, Bistro 31.” Photograph taken by Lara Solt on July 27, 2012, The Dallas Morning News.

Lombardi was born and raised in Forli, Italy. He resided in Forli up until he turned fourteen. At age fourteen, he moved to attend a “hotel school” in a different part of Italy. A few years later, he began traveling around Europe, and working in hotels and restaurants. At the age of twenty-four, he made his way to Dallas where he would eventually settle and begin his journey in creating the Lombardi’s restaurants. His first expansion to an Atlanta location was such a huge success at the time that it made way for him to open several other locations in Phoenix, Orlando, Miami, and Las Vegas.[14] The first location for Lombardi’s new venture landed him right in the heart of downtown Atlanta at 94 (Upper) Pryor Street.[15]

TRINGALI’S

Sandi Tringali was born and raised in Brookhaven, Georgia. At the age of thirteen she began her first job as a busser at The Clock Restaurant in Doraville. She worked at The Clock until 1981, where she started working for the family-owned chain Primos Pizza in Jonesboro. In 1987, Tringali co-owned her first restaurant with her then-husband, Dominic Tringali. The restaurant they opened was part of the Primos chain and was located in Peachtree Corners. In 1993, Tringali sold the Peachtree Corners Primos location. The couple remained working in other Primos locations to help family members until 1995. In 1995, the two began opening Goodfellows Pizza restaurants. The first Goodfellows location was at the intersection of Wieuca Road and Roswell Road, but closed a year later in 1996. The second Goodfellows location was opened directly after the first one closed. This Goodfellows location was situated at Northeast Plaza off of Buford Highway. In 2000, the couple sold the Buford Highway Goodfellows.[16]

Fast-forward to 2003, the year in which Sandi Tringali purchased the space from Lombardi. The restaurant she purchased would later become Tringali’s. The space was bought as the operating Italian restaurant Lombardi’s Ristorante Italiano. The name change to Tringali’s Ristorante Italiano occurred three years later in 2006. The menu and recipes at the time remained the same despite the name change. Lombardi’s (later Tringali’s) became a very popular restaurant for lawyers and judges due to its close proximity to the Fulton County Court House. Customers recognized the restaurant for its “legislative power lunch.”[17]

Lauren Tringali at the entrance of Tringali’s Ristorante Italiano.

Photograph taken by Sandi Tringali on December 23, 2008.

In the six years that Tringali operated Lombardi’s and Tringali’s, she did not notice much change in the population of the area. The location was always what she called an “in and out” spot. Tringali described that the homelessness in the area was prevalent as long as she owned the business. She noted that customers (aside from the regular lawyers, judges, and government workers) tended to be people who were forced to come to the area for responsibilities such as court dates, paying taxes, and other unwanted government obligations.[18]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_QB7wBMt0g

In 2007, the World of Coca-Cola moved from Underground Atlanta to a new location next to the Georgia Aquarium. Tringali explained that the Coca-Cola move caused many other businesses in the Underground area, including hers, to notably decrease. To make up for lost business, Tringali’s started a club scene on the weekends. This added venture did compensate for the lost revenue, however, it only lasted a year. The short life of the club scene at Tringali’s was due to the “wild” aspect that came along with the masses of partygoers. On multiple occasions, irreplaceable items in the restaurant were broken from the large crowds getting out of hand. Tringali’s Ristorante Italiano later closed down in 2009. [19]

LOOKING FORWARD

On December 17, 2014, Mayor Kasim Reed announced the sale of Underground Atlanta. A company based in South Carolina, WRS, Inc., purchased the twelve-acre space for $25.8 million.[20] According to the tentative plans for the Underground area, the public can anticipate that the area will become “a residential living room.” The area is expected to become a “mixed-use complex that includes housing and retail.” The project will, however, shy away from being aimed towards Georgia State University students. The tentative plans call for a “higher end” expansion.[21]

[1] Michael Rose, Atlanta Then and Now (London: Pavilion Books, 2015), pg 19.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Howard L. Preston, Automobile Age Atlanta: The Making of a Southern Metropolis, 1900-1935 (Athens: The University of Georgia Press,1979), pg 48.

[4] Michael Rose, pg 17.

[5] Frederick Allen, Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996), pg 243.

[6] Atlanta City Directory: 1929.

[7] Atlanta City Directory: 1930-1935.

[8] Atlanta City Directory: 1936, 1937.

[9] Atlanta City Directory: 1938, 1939.

[10] “New Tire Company Opens,” The Atlanta Constitution, June 13, 1933, pg 4.

[11] Atlanta City Directory: 1940-1945.

[12] Atlanta City Directory: 1956-1961; “Allright Auto Parks Buys Central Parking,” The Atlanta Constitution, October 9 1964, pg 54.

[13] Sam Machkovech, “The Evolution of Restaurateur Alberto Lombardi,” D Magazine, August 2008, D CEO.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Peter Applebomb, “WHATS DOING IN: Atlanta,” The New York Times, November 19, 1989, sec 5, pg 10, col 1.

[16] Sandi Tringali, interview by Author, December 1, 2015.

[17] Rachel Tobin Ramos, “Popular Capitol lunch spot gets a new name,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 12, 2006.

[18] Sandi Tringali.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Mayor Kasim Reed Announces Sale of Underground Atlanta,” City of Atlanta, December 17, 2014, http://www.atlantaga.gov/index.aspx?page=672&recordid=3201.

[21] Maria Saporta, “Underground Atlanta to be sold for $25.75M to South Carolina’s WRS Inc.,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, December 16, 2014.