Myke Johns, “Georgia History:100 Years of Georgia State University.” Atlanta’s NPR Station, Nov. 22, 2013.

UPDATE: KELL HALL WAS DEMOLISHED IN 2019-2020

If you attended Georgia State University, Kell Hall is forever ingrained in your memory. It was the old building where classrooms were frustratingly hidden away in bizarre half-level floors. There was an odd rampway that you climbed arduously to reach science labs on 4th, 5th, and 6th floors. You remember the gray and beige exterior that seems aesthetically questionable. What If I told you that these features were purposely designed by well-renowned engineers? What if Kell Hall was meant to be a beautiful and technological marvel? What if Kell Hall had a secret past in a different life? In search of these answers, let’s journey into the mysteries of the secret past of Kell Hall.

A Change for Modernity: Atlanta’s First “Automobile Hotel”

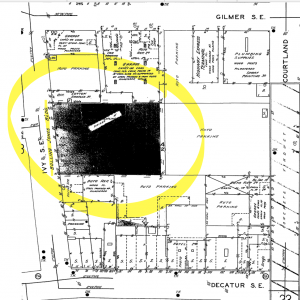

Kell Hall’s long and peculiar history had begun nearly a century ago. Originally constructed in 1925, it was a luxury parking garage named the Bolling Jones Building. Due to its location on the Ivy Street (currently Peachtree Avenue SE), the building was also referred as the Ivy Street Garage.[1] Named after a local capitalist and the proprietor, Mr. Bolling Jones, Jr., the Bolling Jones Building claimed the honor of being Atlanta’s very first mega-parking garage. [2] When tasked with creating a modern skyscraper for automobiles, W.E. Matthews and other Lockwood-Greene & Company engineers carefully designed the Bolling Jones Building to be efficient, sturdy, and aesthetic.[3]

Indeed, the state-of-art skyscraper showcased its magnificence. An observer described it as “a very handsome addition to the Ivy-Edgewood section.”[4] On the exterior, the automobile skyscraper was built with reinforce concrete, an infusion of steel frame and concrete that significantly increased the stability and durability.[5] For decorative embellishment, the concrete exterior was finished terracotta trim, a refined claylike material that saw widespread usage in modernist architectures of early twentieth century.[6] The interior features were testaments of modernity as well. It included colossal six-stories of parking spaces, a service center that offered “washing and polishing, filling crank cases, putting in gas and oil and rendering such other light service” to all types of automobiles, and commercial spaces for lavish boutique stores, commercial offices, and a lounge for chauffeurs.[7] The building also incorporated state-of-art technologies of the period, including automatic sprinklers, steam heat, electric lighting, and elevators.[8] Most interestingly, engineers applied the patented D’Humy ramp design of zigzagged half-levels and condensed ramps, which maximized the space capacity. The half-level ramps reduced its steepness, which allowed cars to drive from the ground to the topmost floor without shifting gears.[9]

Bolling Jones Building (1930s). G1984-30_0255, Office of Public Information Records, University Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Quoted by The Atlanta Constitution as “the most modern structure of its nature in the world” in the coverage of the building’s grand opening in 1925, the Bolling Jones Building boasted as the premier automobile hostelry with the maximum occupancy of 600 vehicles. The construction of Bolling Jones Building required two years of large-scale labor and an immense budget of $1,000,000.[10] For next few decades, the Bolling Jones Building aptly served to the needs of the surging automobile culture by providing ample parking spaces and a service station in the middle of bustling downtown Atlanta. Due to its proximity to the Hurt Building and Five Points, the Bolling Jones Building catered the need of businessmen to store their vehicles during the day.[11]

Transformation from a Garage to Classrooms

Bolling Jones Building (1945). G1973-5_235, President’s Office Records, Photograph Collection, G1973-05, University Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library, Atlanta

In 1946, Georgia State University, then divided as the Georgia Evening College and Atlanta Junior College, urgently needed more classroom spaces for thousands of returning WWII veterans who were eager to obtain college education. Peculiarly, the Ivy Street Garage enticed George M. Sparks, the president of the university, to be the new home for higher education. Although the interior needed substantial renovations to create offices and classrooms, the Ivy Street Garage possessed the necessary conditions for acquisition; it was appraised reasonably inexpensive, located conveniently in downtown Atlanta, possessed a structurally sound infrastructure with reinforced concrete, and provided an ample space of 180,000 square feet. Indeed, the university acquired the building at a bargain price of $300,000. Furthermore, the plethora of post-WWII supplies and manpower cheapened the cost of construction as well; army surplus materials, tools, equipment, furniture, and other odds and ends were salvaged for the renovation. After a quick renovation at the total cost of $100,000, the empty parking lots transformed into viable classrooms for the university. The ramps survived, however; it remained as the primary passageway for pedestrian traffic between floor-levels.[12]

The Anchor of GSU’s Growth

Bolling Jones Building (1946). AJCN048-014d, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The Bolling Jones Building was the first permanent infrastructure for Georgia State University. It perfectly suited the needs of commuter students and night-school students. Since the acquisition by the university in 1945, the Bolling Jones Building served as the main center of operation; it accommodated classes, student center, library, cafeteria, recreation center, and administrative departments. On the roof, patio furniture and large parasols allowed students to relax with the grand view of the city.[13] Albeit unconventional and unique, the building simultaneously and aptly provided a place to learn, unwind, and refuel for the growing university community.

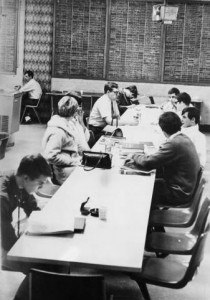

Class Registration at Kell Hall (1963). G1984-26_090, University Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Using the Bolling Jones Building as the foothold, student enrollment began to rise exponentially. In 1949, the student matriculation numbered around 6,000 people. By 1976, the enrollment quadrupled to over 24,000 students. Indeed, Georgia State University extended its influence in downtown Atlanta slowly but surely. Thousands of students occupied the busy city streets among Atlanta businessmen, professionals, and visitors. As the Bolling Jones Building became overcrowded, the university sweepingly expended across downtown Atlanta. From 1950s to 1970s, Sparks Hall, General Classroom Building, Classroom South, Library North, and Student Center were continually erected to provide the various functions that were previously shouldered by the Bolling Jones Building since 1945.[14]

Kell Hall: Celebration of GSU’s Origin

Wayne S. Kell (1920s). G1984-30_0895, Office of Public Information Records, University Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

In 1964, the Bolling Jones Building, affectionately nicknamed “the Rampway” by the students, was renamed as Kell Hall to honor the past contributions of Wayne Sailley Kell.[15] Kell was the first dean of the Evening School of Commerce, the very first name among a long series of designations adopted by Georgia State University. Founded in 1913, the Evening School of Commerce was an extension of the Georgia School of Technology. During evenings, the school aimed to provide commercial training for local businessmen. The adult-oriented instructions offered students with the methods to manage financial assets. As a dean of the school, Kell promoted business entrepreneurship among businessmen and wanted to create a place for commercial education. Although Kell resigned as the dean in 1917 to pursue a full-time career with the Coca-Cola Company, he continued to teach classes and mentor students at the school for nearly two decades.[16]

Female Students at Kell Hall Cafeteria (1946). (AJCN048-014e, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Kell left behind two great legacies for the university. First, he created a business school with a four-year program for the Bachelor of Science in Commerce; no typical evening school offered a full-fledged degree of such magnitude. Unsurprisingly, the school eventually became Georgia’s third Certified Public School of Commerce. Second, he established a co-educational institution, which enrolled women with full-student status. When the male admission declined during the height of World War I in 1917, Kell admitted women to offer new opportunities in professional settings, as well as boosting enrollment in absence of men. By 1933, women received four-year degrees from the Evening School of Commerce; for the time period, it was a progressive feat for female scholars. Indeed, through Kell’s efforts, the University System of Georgia officially recognized the school as an independent higher learning institution in 1932.[17]

Kell Hall Today and the Future

Kell Hall 1st Floor (modern day). “Georgia State University Campus Historic Preservation Plan,” Atlanta Preservation and Planning Services.

Kell Hall 1st Floor (1973). G1984-30_0248, Office of Public Information Records, University Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Over a half-century later, students still receive classroom lectures and laboratory instructions in Kell Hall. The rampway, once used for automobiles in 1920s and 1930s, is still utilized daily by students and faculties. Each year, freshmen face the time-tested trial of finding their science classrooms through the winding rampway. According to GSU Magazine, Georgia State University’s quarterly publication, Kell Hall is targeted for demolition for GSU’s next ambitious expansion project to create a green space and modern infrastructures.[18] Indeed, Kell Hall is the most antiquated and timeworn building in the entire Georgia University campus. Once demolished, Kell Hall will fade into the distant memory of Atlanta’s past. However, for Atlanta historians and connoisseurs of history, Kell Hall will long live on in memories for being the first permanent foothold in downtown Atlanta for Georgia State University. With this article, I wish to commemorate Kell Hall’s legacy as the foundation of growth and prosperity for the thriving urban research institution as we know today.

Citations:

[1] “Ivy Street Garage to Stage Formal Opening.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 24, 1925; “Piles are Driven to Support Auto Hotel Building.” The Atlanta Constitution, Oct. 26, 1924.

[2] “Large Automobile Hotel to be Erected on Ivy Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, Oct. 5, 1924, 17.

[3] “Lockwood Greene & Co. Design Modern Auto Hotel on Ivy Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 24, 1925.

[4] “Large Automobile Hotel to be Erected on Ivy Street.”

[5] “Opening of Atlanta’s New $1,000,000 Automobile Hostelry.” The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), May 24, 1925, 1.

[6] C.A. Galvin, “Terracotta.” The Dictionary of Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), vol. 2.

[7] “Ivy Garage Gives Prompt Car Service. (1926, Apr 11). The Atlanta Constitution, April 11, 1926, 7; “Opening of Atlanta’s New $1,000,000 Automobile Hostelry.”

[8] “Large Automobile Hotel to be Erected on Ivy Street.”

[9] “Lockwood Greene & Co. Design Modern Auto Hotel on Ivy Street.”

[10] “Opening of Atlanta’s New $1,000,000 Automobile Hostelry.”

[11] “Large Automobile Hotel to be Erected on Ivy Street.”

[12] Elizabeth Klipp, “Kell Hall: From Parking Garage to Quirky Classroom Building.” GSU Magazine, Winter Issue 2010.

[13] Ginger Rudeseal, “GSU’s Growth Began in Garage.” The Signal, July 2, 1976, 8.

[14] Ibid, 8.

[15] “It’s Kell Hall at Georgia State.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 22, 1964, 26.

[16] “Georgia State’s First Building Named for Kell.” Rampway Yearbook, Georgia State University, 1895, 21.

[17] “Director Wayne S. Kell.” Past Presidents, Office of the President. Accessed Dec. 1, 2015.

[18] Rebecca Burns, “Cracking the Concrete.” GSU Magazine, 2015, Winter Issue.