The History of Malaria in the US

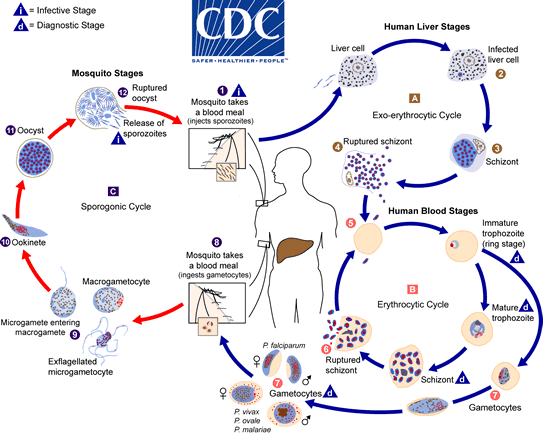

While the history of the CDC begins with malaria, the history of malaria begins far earlier, as far back as ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Based upon writings from these ancient cultures describing periodic fevers characteristic of malaria along with the detection of the malaria antigen from ancient Egyptian remains, it can be concluded that malaria has been around since long before Western civilization, much less the United States. Historical accounts make it clear that malaria found its way into diverse groups of people, eventually spreading through most of Europe, most likely facilitated in part by Roman expansion. Population expansion in the subtropical climates of India and Southeast Asia led to increased habitation of wetlands as opposed to the dry Indus River Valley. This further strengthened the footing of malaria as a parasite of human peoples around the Eurasian continent, as well as Africa.

Malaria soon found its way to the Americas as an unwanted passenger of exploratory expeditions by conquistadors and eventually colonists of the new world. This meagre introduction of malaria was soon followed by a far larger importation at the hands of the Atlantic slave trade. Africans infected with malarial pathogens, both Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum, were brought to the new world as slaves. They were seemingly healthy due to adapted immunity in the form of sickle cell anemia or G6PD deficiency, but were in fact hosts to the deadly pathogen. By the time that the United States had declared themselves independent, malaria had already taken hold in any suitable climate (tropical) in the United States and Latin America. Malaria plagued the United States throughout the 19th century, spreading from coast to coast on the backs of those exercising manifest destiny and causing the deaths of untold numbers of Native Americans in the process.

Efforts were made soon after the turn of the 20th century to control malaria in the United States as well as U.S. occupied Cuba and the areas of construction for the Panama Canal. After the request and reception of funds to the U.S. Public Health Services from congress to fight malaria in 1914, control activities were established around military bases in regions of the United States which seemed particularly “malarious”. While these early steps improved conditions around military bases, it was in 1933 that the Tennessee Valley Authority collaborated with the United States Public Health Services to combat the disease amongst all populations, military and civilian alike. The ability for mosquitoes to breed, and thus spread the disease, was curtailed dramatically by controlling water levels in known mosquito breeding grounds and applying insecticide in all surrounding areas. Through these efforts malaria was, for all intents and purposes, eliminated from the United States by 1947.

Malaria did not go down without a fight in the early 1940’s, however. As World War II fell into full swing malaria proved to be even more deadly than the enemy forces in the beginning of the campaign in the pacific. Malaria Control in War Areas (MWCA) was founded in order to do essentially what the United States Public Health Services had done in 1914: control malaria around military training sites and bases in the Southern United States. MWCA also sought to inform local health officials about methods and strategies to use in the control of malaria, so that they could continue after the war. In 1946 the MWCA gave birth to an offshoot in the form of the Communicable Disease Center (CDC), which immediately began working on further controlling and combating malaria in the United States. The CDC, along with health agencies from 13 southern states, formed the National Malaria Eradication Program in 1947 and made quick strides in its mission to eliminate malaria. Four years and over 4.6 million housespray applications later, malaria was officially considered eliminated from the United States in 1951.

Citations

“A Brief History of Malaria.” Edited by Gelband H, Saving Lives, Buying Time: Economics of Malaria Drugs in an Age of Resistance., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215638/.

“CDC – Malaria – About Malaria – History.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 14 Nov. 2018, www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/history/index.html.

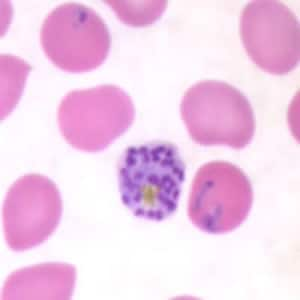

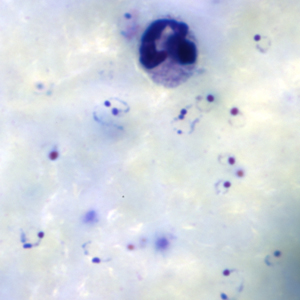

Rings of P. falciparum in a thick blood smear

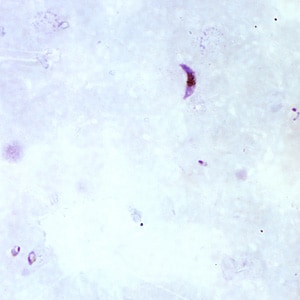

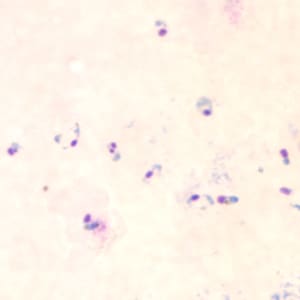

Rings of P. falciparum in a thick blood smear Rings of P. faciparum in a thick blood smear

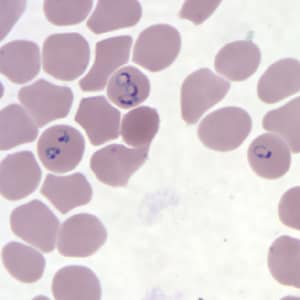

Rings of P. faciparum in a thick blood smear Rings of P. falciparum in a thin blood smear

Rings of P. falciparum in a thin blood smear