Rapid Prototyping Instructional Design: Revisiting the ISD Model – Article Review

Abstract

A mixed-methods investigative study by the authors, Jenny Daugherty, Ya-Ting Teng, and Edward Cornachione, was presented as a paper at the 2007 International Research Conference in The Americas of the Academy of Human Resource Development. The study examined the perceived quality and client experience while utilizing a compressed process of instructional design, referred to as “rapid prototyping.” Findings support the notion that rapid prototyping is a viable approach to creating high-quality instruction and can also enhance the level of client satisfaction and buy-in in the process.

Background

Working in a corporate environment, I have been involved in a number of training and development initiatives that involve the creation of courses of study to address a variety of soft skills in the business environment. As a company that acts as a vendor to our client companies, my firm is frequently tasked with creating high-quality programs in a relatively short period of time. Through my brief and cursory study of ID&T thus far, we have been studying the systematic instructional design process as proposed by Dick and Carey (1978). The reality of the corporate world sometimes does not allow as deep and as linear a process as the study model. Curiosity over a more compressed approach led me to the reviewed article. Though there may be more recent articles which are worthy of exploration, this first foray into the topic only further kindles my curiosity over empirical studies of such compressed approaches to instructional design.

Criticisms of Traditional ISD Models and Rapid Prototyping Defined. The authors cite a number of sources of criticism of traditional ISD models, suggesting that their application in corporate and school settings can be difficult. The models and their processes can be viewed as inflexible, too linear, too slow to implement, and overly analytical.

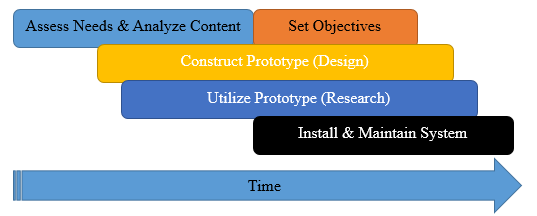

A rapid prototyping (RP) approach can be seen as a way to address some of these criticisms. The intention of RP is to provide a nimble process which reduces time and cost issues while increasing client involvement. RP utilizes an iterative, overlapping ADDIE process. The authors cite Piskurich (2000) who described RP as a “continuing process, with new aspects being added and evaluated in this mode each week until you finally have a complete program.” With RP, one can produce a working model or an actual structure of the design in a prototype fashion, which can be evaluated by the client (and learners and designers) and revised as necessary before much time and expense has been put into a process that may not eventually be acceptable to the client. (From my own experience, this is an approach that is more akin to how instructional programming has been accomplished in my firm.) Figure 1 details an example of an RP approach as envisioned by Tripp and Bichelmeyer (1990).

Figure 1. A Model of Rapid Prototyping Applied to Instructional Design. Taken from Tripp, S., & Bichelmeyer, B. (1990). Rapid prototyping: An alternative instructional design strategy. Educational Technology Research & Development, 38(1), 31-44.

Study Method

The authors used a study group comprised of a client who was also to be the instructor of the material, and a class of forty undergraduate students taking part in a leadership development program. The client also served as subject matter expert who worked along with a design team of three instructional designers, a supervisor, and two staff members. The rapid prototyping (RP) process resulted in the development and refinement of a working model of the instructional product. A test session was conducted with the client facilitator delivering the material. Data were collected through multiple collection sources (interviews, observations, surveys, and audiovisual recording) and included ratings of the quality of instruction, the design process, and follow-up ratings from the facilitator.

The aims of the study were to answer three questions:

- To what extent does RP impact the quality of the training product?

- To what extent does RP impact the role of the client?

- To what extent does RP impact the usability and customization of the training product?

Summary of Findings

The authors utilized field observation of the process and instruction to gauge real interactions and challenges. Observations centered around the delivery and the content to the instruction, which led to refinements in the training product from the initial prototype. Timely changes to materials and methods were incorporated to the final product, with input from the facilitator/client.

The authors utilized a feedback survey based on Kirkpatrick’s first level of training evaluation (participant reactions) and noted that the only low scores were attained in the area of the facility’s appropriateness. Generally high scores were achieved for content, methods of instruction, and materials. Participants did additionally note some confusion over the main concepts of the training and a lack of interaction with others, which the designers addressed by allotting learners more time for small group discussion. The facilitator/client additionally modified the order of the training to address some of these issues. The authors note that because the client was heavily involved in the instructional design and content of the session, that the client was well-equipped to respond quickly to learners’ needs.

The observations and feedback garnered throughout the test session and process of design led the team to further make refinements in content and delivery format to better address learners’ needs and criticisms. Alternate training formats, reordered topics, content revisions, and pre-work were a few of the modifications that the team and the client agreed upon in producing the finalized delivery product.

Study Conclusions

The authors posit that “informed decisions on alternative ways of combining resources to reach similar or even a better level of outcomes is likely to be one of the top priorities in the future for Human Resource Development.” By utilizing a process of RP, a working model of the final product was deployed early in the design process, which allowed for revisions concurrent with the other tasks of the traditional design process (setting objectives, evaluating the design, and continually improving the design and instructional methods). The study’s findings support the notion that RP can provide a viable practice to meet tight timelines and still produce high-quality instructional outputs.

Responding to the study’s questions, the authors noted the following:

- To what extent does RP impact the quality of the training product?

- Based on the perspectives of the learners, designers, supervisors, and the client facilitator the quality of the final training product was deemed to be very high.

- To what extent does RP impact the role of the client?

- The client expressed an overall high level of satisfaction with the process, from design to evaluation. Due to the high level of involvement throughout the process, the client expressed a high level of ownership and satisfaction with the final product.

- To what extent does RP impact the usability and customization of the training product?

- The authors cite Tripp and Bichelmeyer (1990) as having stated that the RP process allows content and method to be adapted to any learner’s needs. This high level of adaptability is one of the main benefits of the RP process. The study showed that the RP process employed allowed the designers and client facilitator to readily adapt the instruction to a variety of needs.

Final Thoughts

Based on the design of the study, the authors seem to agree that RP can be a timely and flexible manner to develop instructional solutions to training needs. However, a study’s utility is only as good as the data it is based on. Thus, while utilizing Kirkpatrick’s first level or evaluation as the basis for the outcome measures is likely acceptable for the purposes of this study, it would be interesting to further evaluate the levels of learning to further address issues of context and depth of learning, providing a more robust measure of the quality of the final product. Also, that the client was so involved in the process and then in the evaluation of the process, I believe leads the client to only be able to respond in the affirmative direction when asked about outcomes. That is, someone who is so invested in a process or a product may not be likely to provide low ratings on these aspects. Lastly, I would be interested to read additional studies which can validate the findings of this study to provide further evidence of the value of an RP process in instructional design.

References

Daugherty, J., Teng, Y., & Cornachione, E. (2007). Rapid Prototyping Instructional Design: Revisiting the ISD Model. Paper presented at the International Research Conference in The Americas of the Academy of Human Resource Development (Indianapolis, IN, Feb 28-Mar 4, 2007). 8 pp

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J.O. (2015). The Systematic Design of Instruction (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Tripp, S., & Bichelmeyer, B. (1990). Rapid prototyping: An alternative instructional design strategy. Educational Technology Research & Development, 38(1), 31-44.