Monthly Archives: December 2015

Reading Summary Two

StandardSCHINDLER, SARAH. “Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination And Segregation Through Physical Design Of The Built Environment.” Yale Law Journal 124.6 (2015): 1934-2024. Academic Search Complete. Web. 20 Nov. 2015.

In Sarah Schindler’s article Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination And Segregation Through Physical Design Of The Built Environment, Schindler addresses the role in which built environment plays in our everyday lives and how it can be utilized as a tool to regulate people’s behavior, livelihood, and accessibility. The author also draws attention to the legal aspect of this architectural exclusion and states that “these less obvious exclusionary urban design tactics”(2015) do not receive the much needed attention and action that they deserve. Schindler’s overall goal within her writing is to raise awareness on the issue of architectural exclusion and help individuals understand architecture’s “regulatory power” and the harms that are associated with them.

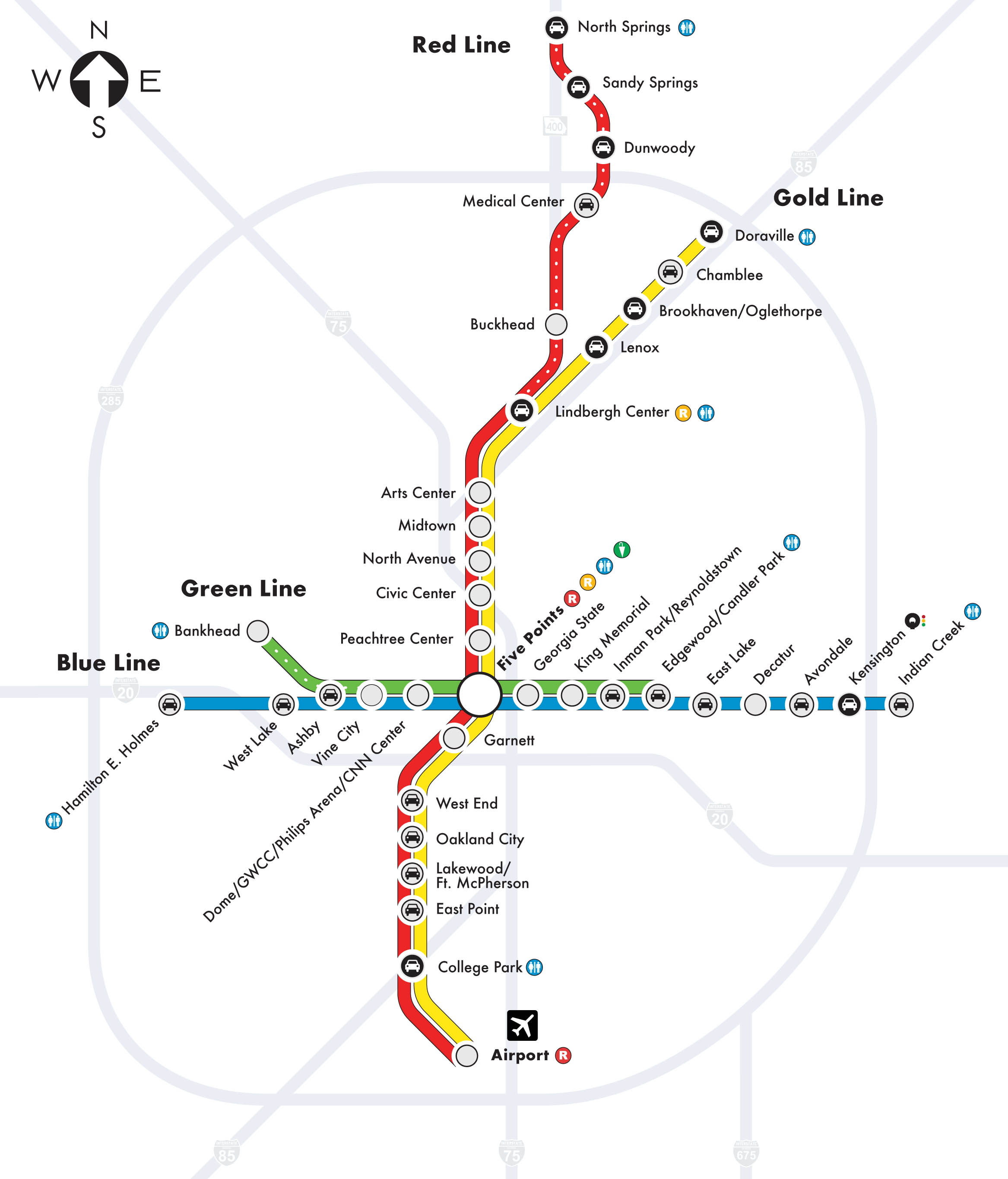

Schindler begins the article by giving examples of architectural exclusion in action. In New York low hanging overpasses were purposefully built to prevent buses from traveling to Jones Beach. Buses weren’t able to travel past low hanging overpasses and as a result people that utilized public transportation (poor and people of color) were not able to visit the beach. Another example of architectural exclusion given in the text was the subway system in Atlanta, Georgia (MARTA). Marta was built and intentionally doesn’t have any rail lines that lead to Northern Atlanta to prevent undesired individuals (poor and people of color) access. The inability to access this area of Atlanta affects job opportunities and the livelihood of the people that utilize public transportation at large.

After readers have a visual understanding of what architectural exclusion looks like, the author goes in depth and explains this form of segregation/ discrimination. In short, architecture is used to exclude. Architectural exclusion is the physical barriers and varied methods to exclude undesirable individuals. People barely pay attention to their physical environments and something as simple as a bench with three seats in the park can be interpreted to something much more complex. When people begin to view their built environments through “regulatory lens[es]” (2015) then they will be able to understand that a park bench doesn’t just have three seats, but it’s a tool to regulate the homeless from sleeping on them.

The author continues the article by addressing the legal aspect associated with the issue of architectural exclusion. She implies that the fault in the United States’ legal system when it comes to the physical acts of exclusion prevalent within society is the inability of individuals to even recognize urban design, architecture, and buildings as a form of regulation. If more attention is given to the less obvious exclusion tactics more legal actions could be taken to prevent and eliminate them.

In conclusion, Sarah Schindler wants readers to view the built world around us through a “regulatory lens”. She also wants to raise awareness and start discussions about how architecture can be used to control behavior and implicitly exclude groups of people. The first step in eliminating this form of segregation and discrimination is to acknowledge it. Step two is to bring awareness to the issue and then the Courts, lawmakers, and legal system as a whole can take action to eliminate and control architectural exclusion.

MARTA system map