“African American integration leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., with Rabbi Jacob Rothschild in Atlanta. January 27, 1965.” AJCP552-028b. Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

In January 27th of 1965, a huge dinner banquet was held in Dinkler Plaza Hotel (known as Hotel Ansley until 1953), located alongside Williams street in downtown Atlanta. The banquet was to congratulate and honor an Atlanta native who just won the Nobel Peace Prize in November 1964, the leader of the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The banquet was a huge success, and was attended by as many as 1,500 people of both black and white races. The New York Times next day reported that “the Dinkler Plaza Hotel was jammed far beyond comfortable capacity with Atlantans” who “stood and sang [We Shall Overcome], the most famous song of the civil rights movement”, and commented that the successful banquet was “symbolic of Atlanta’s attitude on race relations”.[1]

However, though it is not very well known, success of this banquet and the civil rights movement in general, were also closely tied to Coca-Cola, an Atlanta native company that became an international giant. The banquet to honor Dr. King was a symbolic incident which highlighted Coca-Cola Company’s effort to respond to a changing American society, and to the civil rights movement during the 1960’s and 1970’s.

That Banquet in honor of Dr. King was not something that was guaranteed for success from the beginning, at least when the plan for it was revealed in Christmas of 1964. The Atlanta Constitution reported in December 1964, that “there are some strong feelings about the matter” regarding the banquet, and that Atlanta leaders had “mixed feelings” and “some reluctance” in sponsoring the banquet.[2] Another article from the same newspaper stated that “plans for a hometown banquet honoring Dr. King” has “brought behind-the-scenes controversy to Atlanta’s leadership”, and reports that most of the city leaders who were requested to endorse the occasion “have not replied” to the letter, while “a few have replied negatively”. The article also mentions that “at least one highest-level bank executive” made “phone calls to discourage participation”, signifying the extent of opposition to Dr. King.[3] Three years later, when King was assassinated in 1968, The Atlanta Constitution also looked back on the banquet and recalled that “his Nobel banquet stirred controversy” and “resistance to the banquet developed in some circles, especially within the business community”, because “King participated in a strike at Atlanta-based Scripto. Inc.”, acknowledging some Atlantans’ troubled past relationship with Dr. King.[4]

But oppositions in the Atlanta’s business circle was somehow quelled quickly to pave the way for Dr. King. There was someone who silenced the opposition. While writing about the opposition to the banquet, The Atlanta Constitution article at the same time mentions a mysterious figure who was supportive of the banquet; “The president of one the city’s biggest companies” was “attempting to persuade others to unite behind a plan (to hold a banquet)”.[5] Whoever this person was, he was successful. Later it turned out, the man in question was none other than Robert Woodruff, the president of the Coca-Cola Company. Former Atlanta police chief H.T. Jenkins, who served mayors Hartsfield and Ivan Allen, recalled in an interview that the banquet’s organizers, upon facing Atlanta business leaders’ opposition, went straight to Robert Woodruff and he dealt “with this problem and he gave his blessing to their putting the word out that he was for the banquet and would attend if nobody else did”.[6] It seems Woodruff realized that refusing the banquet would result in “the national media to embarrass Atlanta, and by extension, Coca-Cola”, so through Paul Austin the CEO of Coca-Cola at the time, “Woodruff let it be known (..) that he favored the dinner, (..) and the rest promptly fell in line.”[7] However, Woodruff’s biography states that it was the former mayor Hartsfield himself who went to and consulted with Woodruff about the banquet and then told people about his endorsement. Exactly how and to whom Woodruff conveyed his opinion on the banquet remains unclear, but anyhow, it seems clear that Woodruff did exert his influence upon making the banquet a success.[8]

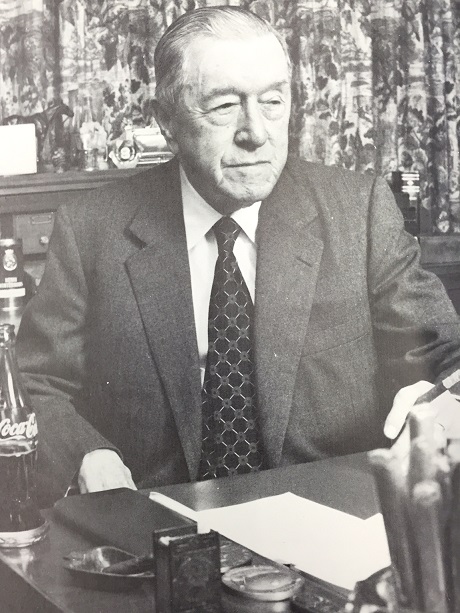

“Robert Woodruff.” Pat Watters. Coca-Cola: An Illustrated History. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. 1978), 250

The banquet was not the only occasion that Woodruff came to be associated with Martin Luther King Jr. When Dr. King was assassinated in April 4th of 1968, numerous accounts states that Woodruff was in the White House with President L.B. Johnson, who personally announced the news of King’s death.[9] Upon receiving the news, Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen recalled in an interview, Woodruff phoned him right away and said, “Ivan, there are a great number of things you have to do. (…) But everything must be done in order that the funeral and the events leading up to it are handled in the proper fashion. Nothing must happen in Atlanta that is not absolutely right. No matter what it costs, it will be taken care of.”[10] The next day Woodruff even sent Coca-Cola company jet-plane to bring King’s wife Coretta Scott King to Atlanta for the funeral, and indeed, Dr. King’s funeral was handled in ‘proper fashion’ and without incident, preventing racial riots and conflicts that broke out in many other Southern cities in response to King’s death.[11] Woodruff also paid for extra expenses for King’s funeral that exceeded Atlanta’s regular budgets like he said he would.[12] Furthermore, he donated money to Atlanta city government for creation of the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center as well.[13]

Such was the extent of Woodruff’s involvement in both events that honored Dr. King’s Nobel Peace Prize and his death. These were all made possible because Robert Woodruff had a tight grab of Atlanta’s city politics as ‘Atlanta’s most prominent citizen’. Police chief Jenkins recalled that mayor Hartsfield would always answer with “I have discussed it with Mr. Woodruff” whenever a questions or objections were raised.[14] Woodruff also served as a mayoral campaign adviser to Ivan Allen who succeeded Hartfield, and asserted heavy influence on him, in addition to providing free Cokes at Allen’s rallies.[15] Therefore, Woodruff was very closely tied with Atlanta’s political and social management, and also to the issue of racial desegregation in the city.

It wasn’t just Robert Woodruff; Coca-Cola Company itself contributed to setting the mood for integration and progress in Atlanta during the Civil Rights era. Starting from 1963 when de-segregation and provision of equal-job opportunities for African Americans became an issue, Coca-Cola responded quickly. Coca-Cola in 1964 pledged to employ and promote workers without regard to their race or color.[16] A move also of considerable import was also made by the company in 1968, as Coca-Cola supported the publishing of an illustrated black history magazine Golden Legacy which wrote stories of black heroes as such as Toussaint L’Ouverture, and distributed them free of charge, to “help develop a richer understanding and appreciation of the American heritage”, and to “promote better relations between individuals and groups.”[17] Also in 1968, Coca-Cola’s declared to hire more black people to their sales department. Coca Cola’s sales force had “Negroes up only about 3 percent”, and “as one of the leading equal employed in the area of Atlanta”, Coca-Cola Headquarter in Atlanta tried to address employment issue by “stepping up its program of tapping additional Negroes in the area of merchandising and sales promotion”, a move which was “hailed as a significant step” by local black leaders.[18] In the same year, the Atlanta chamber of Commerce’s aid program designed to promote “the field of black entrepreneurship” and “assist new Negro businesses” was also seen to be headed by Eugene Boyd, a vice president of the Coca-Cola company.[19]

“Coca-Cola USA Sponsors Environment for Business Dialogue” Photo Standalone, The Atlanta Daily World, Apr. 22, 1971, 2

These kinds of commitments continued onto the 1970’s as well. The Atlanta Daily World reported in 1971, Coca-Cola began an educational scholarship program to aid black students to show its support of African American communities.[20] And in 1975, Coca-Cola commemorated National Black History Week by announcing that it commissioned a black artist Calvin B. Jones to paint famous historic black heroes as such as Dr. King, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglas.[21] Further examples of Coca-Cola’s considerable effort to address the issue of racial equality are abundant in media archives.

However, regrettably, Coca-Cola’s relationship with African American communities were never idealistic nor were they free of turbulence. First of all, Robert Woodruff himself was no supporter of Civil Rights Movement itself. Records show that Woodruff even had racist tendencies. Even though he personally treated black people under his employment with patronizing respect, he backed a white supremacist Herman Talmadge in Georgia state senate, and once likened the civil rights activism to “protecting right of a chimpanzee to vote”.[22] Woodruff was also a personal friend of Edgar Hoover who opposed and harassed Dr. King, and supported FBI’s activities.[23] Also, even though they boasted their promotion of racial equalities in terms of public relations, Coca-Cola Company failed to address that issue of race within their own corporate body. Even though African Americans consisted of more than 25% of the total Coca-Cola workforce by 1990’s, there “had been just one black senior vice president in the entire history of the company” up until then.[24] Coca Cola Company’s internal problem of racial inequality and discrimination toward black employees in terms of promotion and wages, were only addressed after a bitter vocal struggle and a class-action lawsuit against racial bias in 2000.[25]

Then, why did Robert Woodruff tried to honor Dr. King’s legacies even though he probably had no burning love for Dr. King or King’s civil rights activism? And why did Coca-Cola Company attempted to publicly address racial equality issues, despite having troubles with or lacking true respect to said issues? Condemning them for hypocrisy would not do justice; rather, it would be better to look for the reason why they acted the way they did. The simplest and clearest answer is present in 1963 Coca-Cola Atlanta Bottling Company statement, which was put out after black ministers organized a Coca-Cola boycott because the company did not employ enough black men. After agreeing to create equal job opportunities, the company spokesman said, “we plan to work for the benefit of all the citizens of greater Atlanta – both Negro and white”, and hoped “that our Negro citizens who boycotted us will now return to the practice of buying and enjoying Coca-Cola”, and “that they will bear no further ill-will toward a company and a product which, we think, over the past years has contributed a great deal in many ways to the Negro community.”[26] There it was. “Negro Citizens” returning to the “practice of buying and enjoying Coca-Cola” was all that mattered.

Throughout the civil rights era, boycotting was an effective tool for urging change to conservative businesses, because “cost exposure stimulated concessions”.[27] Black civil rights group as such as ‘Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)’ actively employed boycotting as a mean addressing business racial inequality, and Coca-Cola was no exception to that. For example, in 1963, CORE demanded Coca-Cola to present African Americans in television and print advertisements, and “added a thinly veiled threat that selective purchasing committees would aid us in our bargaining position”, to which Paul Austin, CEO of Coca-Cola, had to grudgingly comply, while blaming Pepsi-Cola for instigating the boycotters.[28] In this sense, Robert Woodruff and Coca-Cola Company was soundly responding to the civil rights movement, business-wise. When Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. consulted Woodruff about testifying for civil rights bill in 1963, Allen told Woodruff that “Atlanta business would suffer from violence if some accommodation weren’t made”, and Woodruff’s reply was “you are probably right.”[29] As can be seen here, what moves influential business giants to endorse progressive civil causes are not ideals, but their desire to earn more profits. One might disregard such movements for being hypocritical, but regardless of their inner motives, when business leaders of Atlanta at the urge of Woodruff, gathered at Dinkler Plaza hotel to honor Dr. King in January 1965, (because not doing so would have been ‘bad for business’) it was moving enough for King himself, who remarked with tears in his eyes that the ceremony was “quite a contrast to what I face almost every day … and it’s a fine contrast to have people say nice things.”[30] Woodruff and Coca-Cola, driven by their desire for maintaining business opportunities, assisted Dr. King and Black communities, and that helped Coca-Cola pave its way through the Civil-Right Era and the desegregation process. They acted out of practical, not morale, grounds, but one doesn’t have to be entirely sincere in supporting a social change; what matters is the action and outcome that affected the course of history.

“Atlanta held a celebratory dinner for King. Blacks and Whites from all walks of life gathered together to honor the Nobel Laureate.” Charles Johnson and Bob Adelman, King: The Photobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. (New York: Viking Studio, 2000), 163

Left: “Ansley-Dinkier Hotel Stirrup Room. Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers. August 18, 1953.” LBGPF5-034b, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Right:The place where Dinkler Plaza Hotel was before until 1974. Photo Taken by Author. April. 2016.

[1] “Atlanta Praises Dr. King at Fete.” The New York Times, Jan. 28, 1965, 1.

[2] “City’s Leaders Express Cautious, Mixed Feelings.” The Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 29, 1964, 2.

[3] “Banquet to Honor Dr. King Sets Off Quiet Dispute Here.” The Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 29, 1964, 2.

[4] “His Nobel Banquet Stirred Controversy.” The Atlanta Constitution, Apr. 5, 1968, 16.

[5] See Footnote 3.

[6] Pat Watters. Coca-Cola: An Illustrated History (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1978), 246

[7] Mark Pendergrast. For God, Country and Coca-Cola: The Definitive History of the Great American Soft Drink and the Company That Makes It. Third Edition: Revised and Expanded. (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 266-267

[8] Charles N. Elliott. Mr. Anonymous: Woodruff of Coca-Cola (Atlanta: Cherokee Publishing Company, 1982), 189

[9] Ibid.

[10] Pat Watters. Coca-Cola, 247

[11] Mark Pendergrast. For God, Country, and Coca-Cola, 271

[12] Rebecca Burns. Burial for a King: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Funeral and the Week That Transformed Atlanta and Rocked the Nation. (London; New York, N.Y.: Scribner, 2011), 35

[13] Charles Elliott. Mr. Anonymous, 264

[14] Pat Watters. Coca Cola, 245

[15] Rebecca Burns. Burial for a King, 64

[16] “Coca-Cola Progress, Policy Noted.” The Atlanta Daily World, Mar. 15, 1964, 1.

[17] “Coca-Cola Co. Offer Negro History Book.” The Atlanta Daily World, Feb. 2, 1968, 2.

[18] “Atlanta Coca Cola Co. Seeks to Attract More Negroes In Sales.” The Atlanta Daily World, Feb. 6, 1968. 3.

[19] “Aid Vowed For Black Business.” The Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 19, 1968, 77.

[20] “Coca Cola Announces Aid to Black Students.” The Atlanta Daily World, Feb. 23, 1971, 2.

[21] “Black Artist Is Commissioned By Coca Cola To Paint Black Heroes.” The Atlanta Daily World, Jan. 23, 1975, 3.

[22] Mark Pendergrast. For God, Country, and Coca-Cola, 252

[23] Ibid, 267

[24] Constance L. Hays. The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company. (New York: Random House, 2004), 203

[25] Ibid, 197-215

[26] “Coca-Cola Pledges Continued Community Support, Cooperation.” Atlanta Daily World, Oct. 13, 1963, 1.

[27] Luders, Joseph. “The Economics of Movement Success: Business Responses to Civil Rights Mobilization.” American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 4 (2006): 963-98.

[28] Mark Pendergrast. For God, Country, and Coca-Cola, 265

[29] Ibid.

[30] David L. Lewis. King : A Biography. 2d ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 267