About 13,500 species of lichen are composed of fungi that come from the phylum Ascomycota. Ascomycota, depending on which stage of the life cycle they are in, can transform from an asexual phase into a sexual life cycle and vice versa. Ascomycota contains a single-celled spore form––the specific type depends on the species of Ascomycota––and a filamentous mycelium (Taylor, Spatafora, Berbee, 2006).

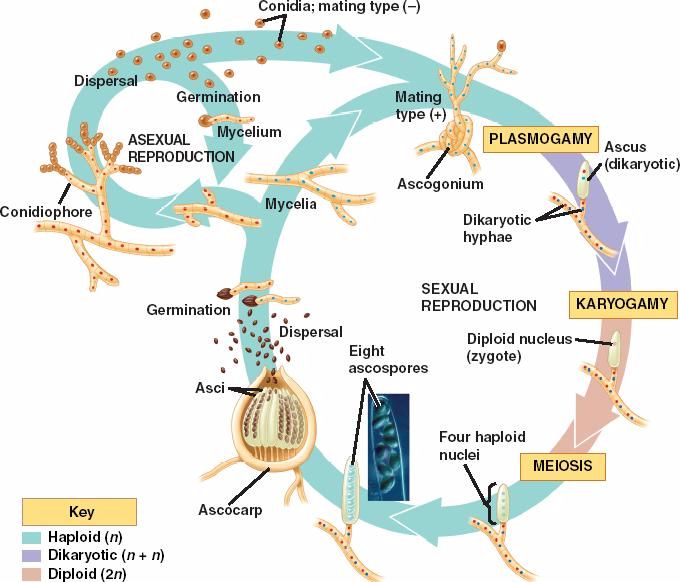

In the asexual life cycle, the mycelia use specialized hyphae, called conidiophores, to branch off the mycelia and begin producing spores. These spores are called conidia or mitospores and are haploid cells that will undergo mitosis. The spores that complete mitosis will remain dormant and wait until ideal environmental conditions are present in order to germinate to produce new mycelium. Asexual reproduction is the most common form of reproduction as it only involves a single mycelium.

During the sexual reproduction phase, it begins in the mycelium, but unlike asexual reproduction, there will be at least one female and one male mycelium. The males have an antheridium and the females have an ascogonium––their respective reproductive organs. Once the two organs fuse, plasmogamy begins, which is the fusion of the cytoplasm between the two organs. These fused organs are called an ascocarp, and they begin to grow sac-like cells within the ascocarp called ascus. Within the ascus, male and female genetic information is fused in the nuclei when the ascospores undergo karyogamy to form a diploid zygote. The diploid zygote will undergo meiosis, and the ascus will now contain four unique haploid nuclei. The newly formed haploid cells will now undergo mitosis and cell division to form eight haploid spores that are then released and set to germinate and form new hyphae in new environments (Learning, n.d.). Spores can be released by wind, water, mechanical force, or insects. Their goal is to ensure there is less competition for resources and a suitable substrate for germination.

Ascomycota is such a vast phylum that it also contains many different kinds of single-celled yeast. These yeasts mainly reproduce via budding or fission a form of asexual reproduction. Budding is the process where a small portion of the cytoplasm of the parent cell becomes separated and form a daughter cell. Fission is the equal division of the cytoplasm into two daughter cells the same size. Under extreme conditions like starvation, yeasts may reproduce sexually. This happens when two different mating types fuse cytoplasm and nuclei. The process forms a diploid cell where it will undergo the same process as other Ascomycota to release spores.

In order to supply nutrients, Ascomycota is heterotrophs and digest living or dead biomass. They secrete digestive enzymes that break down organic material into small molecules, and the small molecules are absorbed through the cell wall. Depending on the specific species, these fungi can obtain nutrients in almost any imaginable pathway. Most species live on dead plant cells that find their way to the forest floor. Some act as parasites and receive metabolic energy and nutrients from the host’s cells. Ascomycota can also form symbiotic relationships with cyanobacteria, called lichens, where they gain nutrients through photosynthesis. Ascomycota can digest organic substances ranging from plant cellulose all the way to wall paint and aircraft fuel (Foundation, n.d.)

Here’s a quick video showing various species of lichen growing when exposed to nutrients

Sources:

- Learning, L. (n.d.). Biology for Majors II. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-biology2/chapter/ascomycota/

- Foundation, C. (n.d.). 12 Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.ck12.org/book/CK-12-Biology-Advanced-Concepts/section/12.27/

- Taylor, J. W., Spatafora, J., & Berbee, M. (2006, October 9). Ascomycota. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from http://tolweb.org/Ascomycota